The Evolution of Health Information Networks: The Road to TEFCA

Navigating Exceptions, Workarounds, and the Path to a Robust National Health Data Exchange

If you’re a provider, payer, developer, or any other stakeholder considering TEFCA, but confused, hopefully this article helps. If not, reach out to us at HTD Health to have a conversation and learn more.

In Interop Summer High, the article articulated how certain organizations mentioned in Epic v. Particle might be using the “On Behalf Of” (OBO) principle to serve Operations use cases:

MDPortals (as well as their recent acquirer, Reveleer) was blocked because of accusations of using the Treatment purpose of use to help health plans (based on marketing and messaging such as this). This could be misuse if true, given that health plans themselves can never claim Treatment purpose of use, although they may have been using the principles of secondary use or On Behalf Of as workarounds.

Later, I mentioned that recent Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) announcements show that they are architecting the framework to build paved paths for different use cases and to close workarounds that accomplish the same outcomes:

The one takeaway from this summer of TEFCA progress should be that, in one way or another, the gaps in today’s health information networks will be plugged, building paved paths and delegitimizing the workarounds of secondary use and On Behalf Of. Other use cases may be announced. Progress will continue. So it is time to get on the TEFCA train or be left behind.

After releasing the story, I received a few questions asking what exactly the OBO workaround was, as Epic v. Particle only explained what OBO was, and Epic v. Particle 2: The Problem of Secondary Use only explained the secondary use workaround. Moreover, the Recognized Coordinating Entity (RCE) that governs TEFCA recently announced the concept of Delegation of Authority (their heir to Adjacent Products and OBO applications), which Carequality has stated they will also align with.

This all is a good prompt to walk step-by-step through the history of health information networks leading to OBO, the unique ways some organizations are using it that challenge network health, and how interoperability leaders are fixing those problems to build a network of safe, ubiquitous access to health data.

Network Basics

Before diving into the networks’ newer exceptions and categories for ancillary applications, it makes sense to run through a bit of history, some foundational concepts, and the general dynamics of network effects.

As we run through this, remember that ethics, the law, and the rules of networks are intertwined yet separate things. Ethics guide the moral principles and values that should inform decision-making in healthcare data sharing. The law provides the legal framework and requirements that all participants must adhere to, such as HIPAA in the United States. Network rules, established by organizations like Carequality and CommonWell, define the specific operational standards and protocols for data exchange within their ecosystems.

While these three domains often align, they can sometimes conflict or leave gray areas:

Ethical considerations might encourage broader data sharing to improve patient care, but legal restrictions or competitive considerations could limit such sharing.

Network rules might allow certain practices that, while legal, could be ethically questionable in terms of patient privacy or data commercialization.

Rapid technological advancements might outpace legal frameworks, leaving network rules to fill the gap until legislation catches up.

The laws we make form the floor of how we protect, share, and interact in this domain. Network rules need at a minimum to conform to the law, but may go further to accommodate ethical considerations, industry best practices, and the specific needs of the healthcare ecosystem. These rules often serve as a bridge between legal requirements and ideals, addressing gaps in legislation and setting higher standards for data exchange and protection.

Network rules also protect against risky entities or use cases that, while legal, potentially threaten network viability. For example, credit card networks often have rules that go beyond legal requirements to protect against fraud and maintain consumer trust. They may restrict high-risk merchants (like online gambling sites, adult entertainment, cannabis, or certain cryptocurrency exchanges), impose chargeback limits, require specific security standards (PCI DSS), implement extra anti-money laundering measures, or set transaction velocity limits. These rules often serve as a bridge between legal requirements and ideals, addressing gaps in legislation and setting higher standards for data exchange and protection while safeguarding network viability.

All this to say, this article does not cast judgment on any organizations or individuals involved in exchange today but intends to detail the history of policies, roles, and structure in a way that a broad audience can understand.

The EHR Era

Carequality is a trust framework, which from an architectural standpoint means that they provide:

An organizational directory to help framework members understand and identify the other participants on the network

Certificates to prove framework membership when interacting with one another

Implementation guides to ensure standard transactions between members

Governance to resolve any disputes or issues

There are two main roles:

Implementers: An organization that has signed the Carequality Connected Agreement and been accepted as such by Carequality.

Carequality Connections: An organization that is properly listed in the Carequality Directory. A Carequality Connection (CC) may have the Implementer as its parent node or another Carequality Connection as a parent node.

Implementers were generally EHRs, with individual health systems or practices as their Carequality Connections:

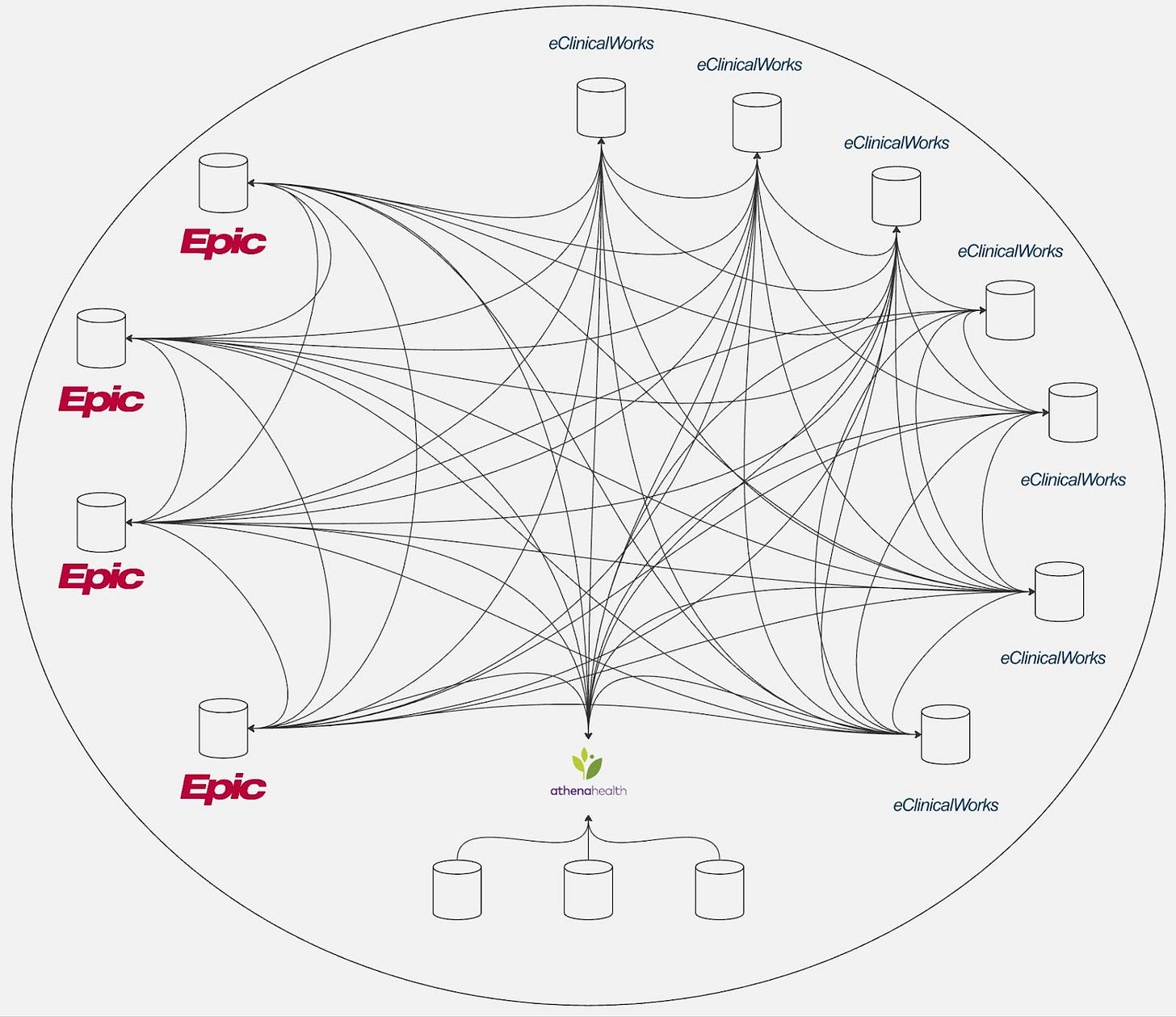

When Carequality started, the resulting network that formed was very decentralized, with most nodes connecting point-to-point. With no centralized record locator service, Carequality Connections must search all other nodes to comprehensively identify whether a patient has been seen across the network.

Much like the telecom industry and ISPs, healthcare has more than one nationwide network, another being Commonwell. While Carequality and Commonwell connect to one another today and are viewed by many as one major mega-network, Commonwell is slightly different in that it acts as a record locator service for its members, storing the demographics of patients to better identify sites of care.

From a participation perspective, it has analogous roles:

Service Adopters: This is functionally equivalent to Carequality’s Implementer. These are vendors who certify their products with Commonwell and then onboard their customers.

Authorized Users: This is functionally equivalent to the Carequality Connections concept, including allowing a chain of Authorized Users.

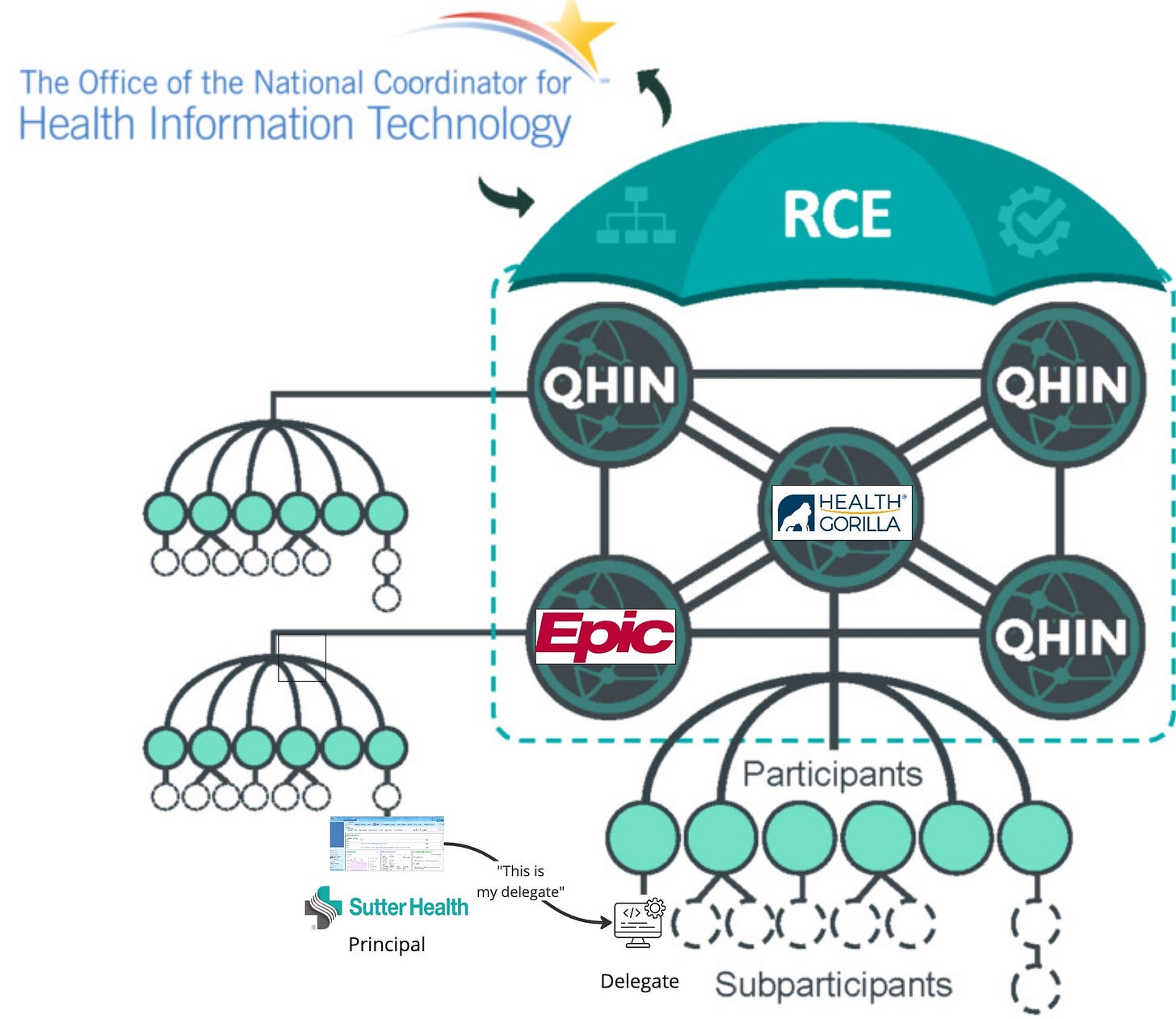

TEFCA is similar in structure to Carequality - it is decentralized. However, their version of Implementer, the Qualified Health Information Network (QHIN), has a much more rigorous process, leading to fewer total QHINs than Implementers.

Additionally, TEFCA divided the Carequality Connection role into Participants and Subparticipants. Despite reading TEFCA documentation ad nauseum for months, I still haven’t divined any difference between the two, except that Participants contract with QHINs and Subparticipants with either Participants or Subparticipants. A full primer on TEFCA can be found here.

Although the roles are fairly simple, the Implementers and CCs can be categorized further by how they store data and structure themselves in the directory.

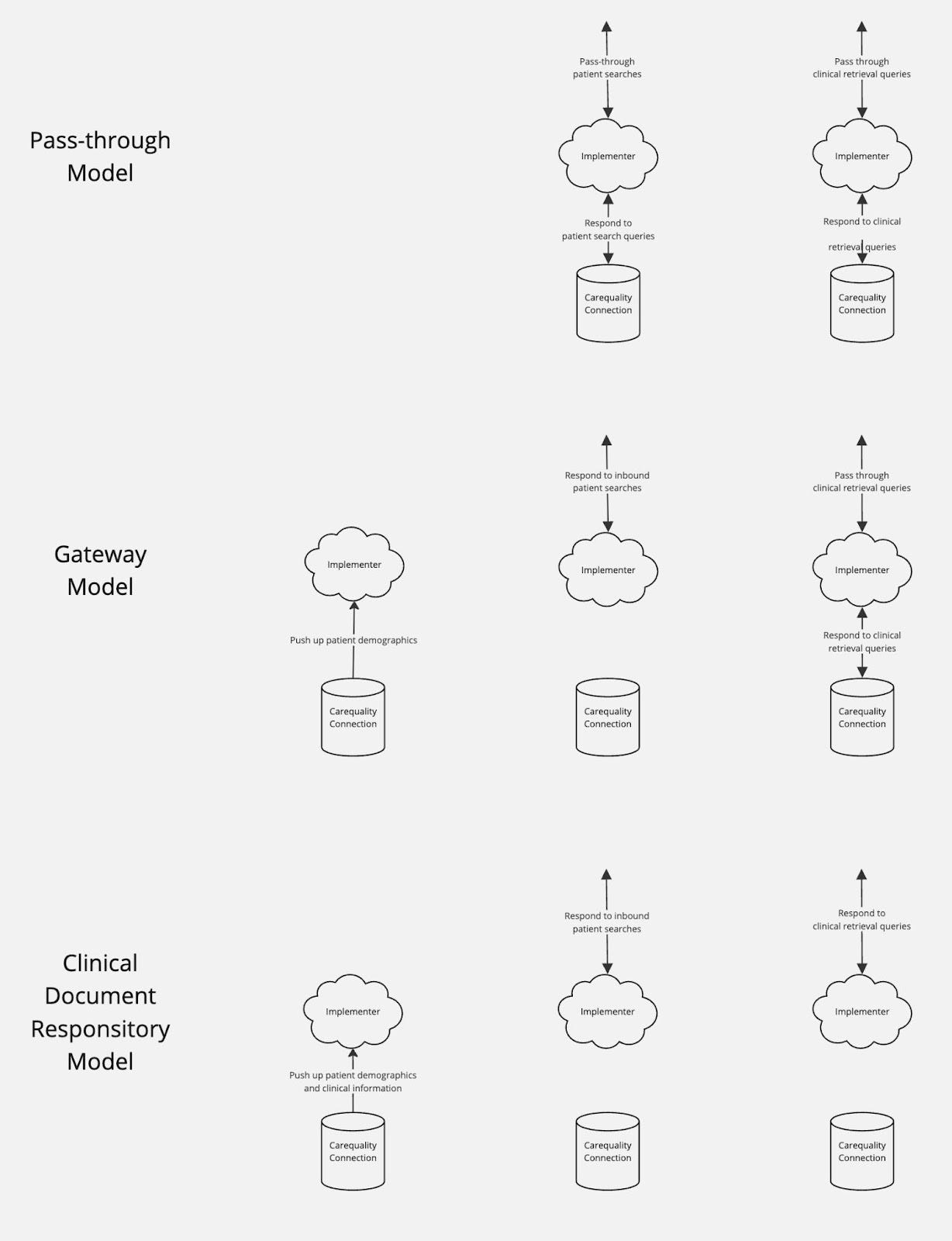

Some Implementers are simple pass-throughs, storing no patient or clinical data themselves and forwarding requests to their CCs.

Others act as gateways, where they may store underlying patient demographics for all patients seen at their CCs, such as athenahealth

Some implementers even act as a clinical data repository, storing their underlying CCs’ clinical data to respond to queries on their behalf.

Regardless of the roles, architecture, or approach, all members of these networks still were subject to the Treatment and Reciprocity concepts mentioned in Epic v. Particle. The right to query stemmed from the Carequality Connections providing care – the providers on the EHRs registered as Implementers or the providers using software of an on-ramp – and not the Implementers themselves, as they typically do not provide care.

As detailed in Metcalfe’s Law, the ideal network-effect product has an exponential value increase as the network size grows. However, most network-effect products do not achieve this ideal (as detailed in 2002’s “Confronting the Limits of Networks”) due to:

Saturation: Certain types of networks hit a point where new users are unlikely to add value, such as Uber adding extra drivers

Cacophony: Networks can be overwhelming when too many people join, such as a Slack or Teams workspace that has too many users

Clustering: Members consistently use only a small part of a network that is available to them

Contamination: Users sometimes actively reduce or destroy the value of a network out of malice or desire for gain

We can think about Carequality, Commonwell, TEFCA, and other health information networks with these concepts in mind.

Saturation: Given that all healthcare organizations have differentiated supply (care is unique and specific to that organization), their potential contribution uniquely adds to the longitudinal record of a patient, limiting the risk of saturation

Cacophony: While this is a problem on the network, in that the volume of health data for a patient can be overwhelming, it can be mitigated with the appropriate tooling - embedding data in workflow, summarizing data, and allowing the data to be interrogated by LLMs

Clustering: Clusters exist on the networks, in that healthcare has a physical element to it that means geographically close organizations have strong patterns of exchange. However, the growth of virtual care, increasing rates of relocation, and other factors are shifting healthcare to a more national clustering

Contamination: The main risk for Carequality and Commonwell is the type of incremental user added. Are they actively adding value to the network and encouraging robust exchange?

The power of Reciprocity as a concept is that it inherently makes all new entries “contributors”, eliminating the negative effects of “pollutants” and “neutrals”:

Contributors: Users who actively add value to the network by participating in robust exchange. In the context of health information networks, this would be healthcare providers who regularly update and share unique, comprehensive patient records

Neutral: Users that neither significantly add to nor detract from the network's value. In health information networks, these might include healthcare providers who share limited data, but also do not query for records

Pollutants: Users that actively reduce or destroy the value of a network out of malice or desire for gain. In health information networks, pollutants could potentially include entities that deliberately share inaccurate or incomplete patient data or participants who misuse patient data accessed through the network, violating privacy laws or ethical standards

a16z’s “The Dynamics of Network Effects” crisply shows how network value can be affected by these incremental users:

Networks don't die overnight. They plateau and stagnate, shedding users as the value decreases. This decline often happens gradually, as the network fails to maintain its value proposition for existing users or attract new ones.

DirectTrust is a good healthcare-specific example of such a plateaued network. A nearly ubiquitous network for secure health information exchange, DirectTrust initially saw widespread adoption for its secure email capabilities in healthcare, especially as the government included relevant capabilities as certified health technology criteria. However, like many networks, it has faced challenges in maintaining growth and relevance in a rapidly evolving healthcare technology landscape. This stagnation can be attributed to contamination - the provider directory included many invalid and nonfunctional entries, such as providers that changed organizations or even passed away. While DirectTrust remains a usable tool and continues to innovate, it has not reached the ceiling of its potential due to this problem and resulting network unreliability.

Anyway, circling back to healthcare in the EHR era - with Reciprocity strictly enforced and Treatment baked into EHR functionality, incremental users only improved the network value. As a result, Carequality and Commonwell saw Metcalfe’s Law in action in the 2010s, as the major EHRs all joined (or at least tried to), especially after the two health information networks reached an agreement in 2018 to integrate with one another.

The On-Ramp Era

Throughout the EHR era, the general structure of EHRs as Implementers (i.e. parent nodes) and providers as child nodes remained nearly universal. Two pressures changed this, though:

Network growth

History doesn't repeat itself but it often rhymes. Regardless of industry, fully decentralized peer-to-peer (P2P) architectures have scalability issues - if every node must be searched to identify where records are, then overall query volume becomes a function of number of patients multiplied by the number of nodes. As decentralized networks grow, they tend to evolve towards hierarchical or semi-centralized structures to maintain efficiency. This evolution towards efficient record location often involves:

Indexing mechanisms: Systems that efficiently organize and locate data across a distributed network

Intermediary nodes: Specialized nodes within a network that facilitate communication or perform specific functions for other nodes

Layered architectures: Network designs that divide functionality into distinct layers, each building upon the services of the layer below it.

We see this pattern across industries:

Early decentralized file-sharing networks like Gnutella ran into severe problems as the network scaled, with dropped connections and high bandwidth costs.

They resolved this problem with record location tooling: distributed hash tables to share indices of where records lived and supernodes that acted as routers).

Similarly, the fully decentralized Bitcoin network has well-known scalability issues, although these are largely self-inflicted by the cryptocurrency’s design.

Bitcoin is adopting the Lightning Network as a second-layer solution akin to the P2P file-sharing supernodes.

So it’s not surprising that as Carequality has grown to tens of thousands of nodes, many traditional Implementers have moved to a layered architecture with intermediary nodes and indexing mechanisms: the gateway or clinical data repository models.

When done right, the gateway architecture is generally a good pattern, reducing total network volume in that other organizations only need to search at the gateway level for a patient, rather than each underlying CC. This reduces overall congestion, improving reliability, response rates, and uptime and avoiding one form of cacophony.

However, the clinical data repository introduced two conflicting priorities:

Fulfilling the Reciprocity requirements of the network necessitates synchronizing large amounts of clinical data from the provider system to the CDR

The high complexity and large burden of such synchronization acted as friction to implementation at provider sites

On-ramps

In the early 2010s, Carequality and CommonWell Health Alliance experienced rapid growth as major Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems joined their networks. However, by the end of the decade, membership growth began to plateau. The long tail of smaller EHR vendors, struggling to meet customer demands and regulatory requirements, found it challenging to prioritize data exchange. Even when these vendors showed interest, the complex standards and lengthy certification processes used by the networks posed significant barriers to adoption.

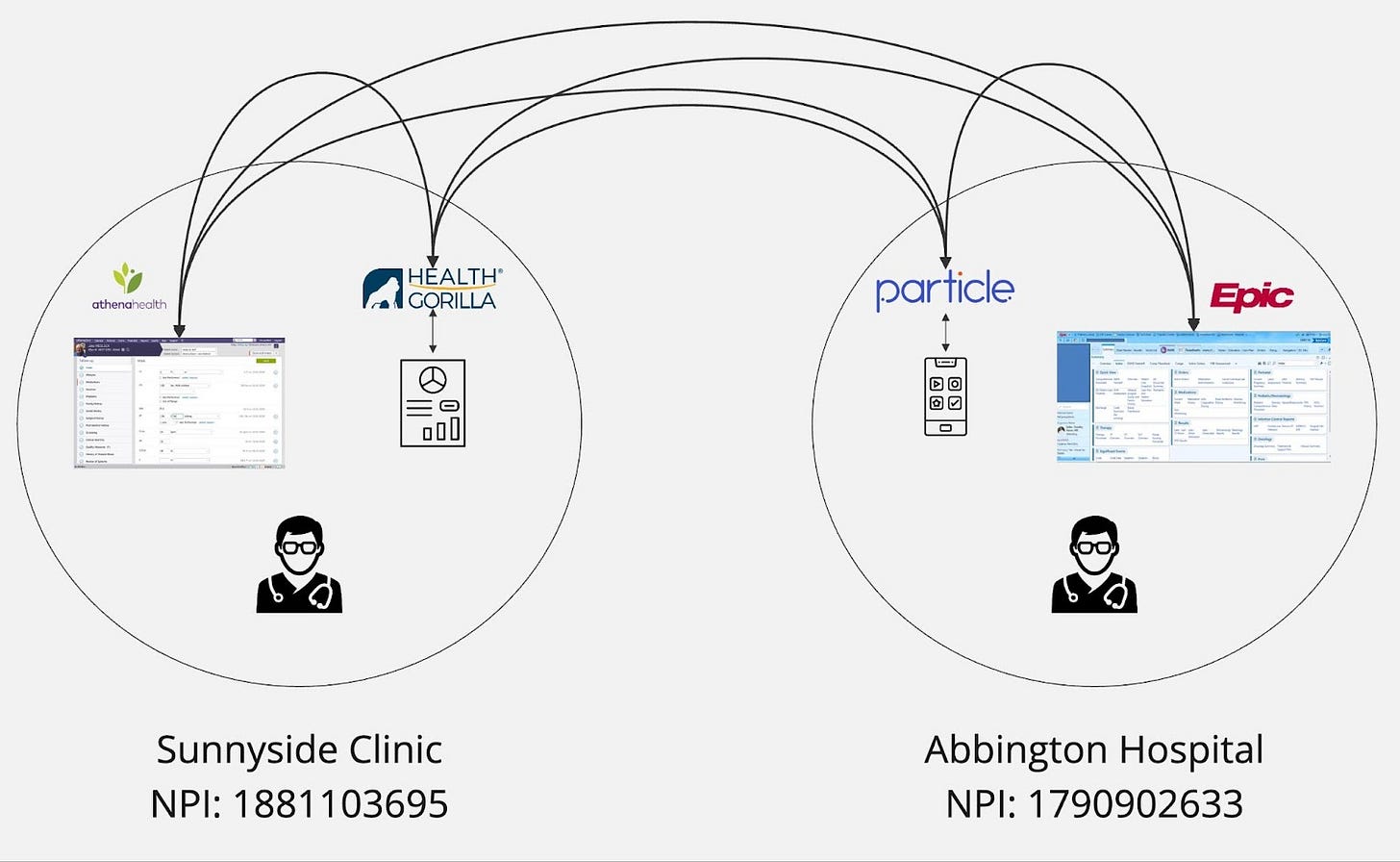

To address these challenges, the networks introduced programs like “Commonwell Connectors”. These programs allowed interoperability and integration platforms like Health Gorilla, Particle Health, Redox, Zus Health, Kno2, and Metriport to join, enabling innovative approaches to connect remaining providers. These new methods included easier APIs, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) translations, data augmentation, and even the development of direct EHR database connectivity.

The addition of these on-ramps significantly expanded the networks to new participants. Virtual care providers and tech-enabled practices that had developed their own EHRs were early adopters. This initial success paved the way for EHRs and other software vendors that had not previously joined the networks, such as PointClickCare, MEDHOST, Healthie, ModMed, and Canvas Medical.

These on-ramps typically employ a gateway or Clinical Data Repository (CDR) approach for simplicity. Regularly pushing or extracting data is easier than attempting to make it available upon demand. More cynically, these companies may use a CDR architecture and store the data locally to have more control and ownership, potentially envisioning selling it in a deidentified fashion.

In terms of implementing the CDR model, on-ramps also face an additional constraint beyond the higher implementation burden: their revenue is directly tied to their customers going live on the health information networks. In contrast, network participation is not the main revenue stream for EHRs or other more traditional participants.

The business model of on-ramp companies, which focuses on rapidly connecting nodes to health information networks, can sometimes create tension with the principle of full Reciprocity. These companies face pressure to onboard clients quickly to generate revenue and demonstrate growth to investors. This urgency may lead to prioritizing speed over comprehensive implementation of Reciprocity rules. Additionally, some clients may be hesitant to share their data fully, creating a challenge for on-ramps to balance client preferences with network requirements. However, it's important to note that many on-ramp companies do strive for full Reciprocity and work to educate their clients on its importance. The varying levels of Reciprocity observed among on-ramp connected nodes likely reflect a combination of factors, including client readiness, technical capabilities, and the evolving understanding of Reciprocity's role in the broader health information ecosystem.

As a result, we observe a wide range of Reciprocity from nodes connected by on-ramps: many are full contributors, but some add only the bare minimum and some avoid Reciprocity altogether. Notably, at least one on-ramp initially created fake "patient not found" responses for all inbound queries, allowing their customers to query without Reciprocity.

While overall Reciprocity has improved as these companies have matured, the fact remains that on-ramps have a distinctly different incentive structure and varying levels of customer Reciprocity. While the on-ramp expansionary era undoubtedly has upside and benefits in terms of expanding to underserved providers, the variation in participation levels presents ongoing challenges in trust, culminating in and exemplified by the Epic v. Particle dispute.

The Ancillary Applications Era

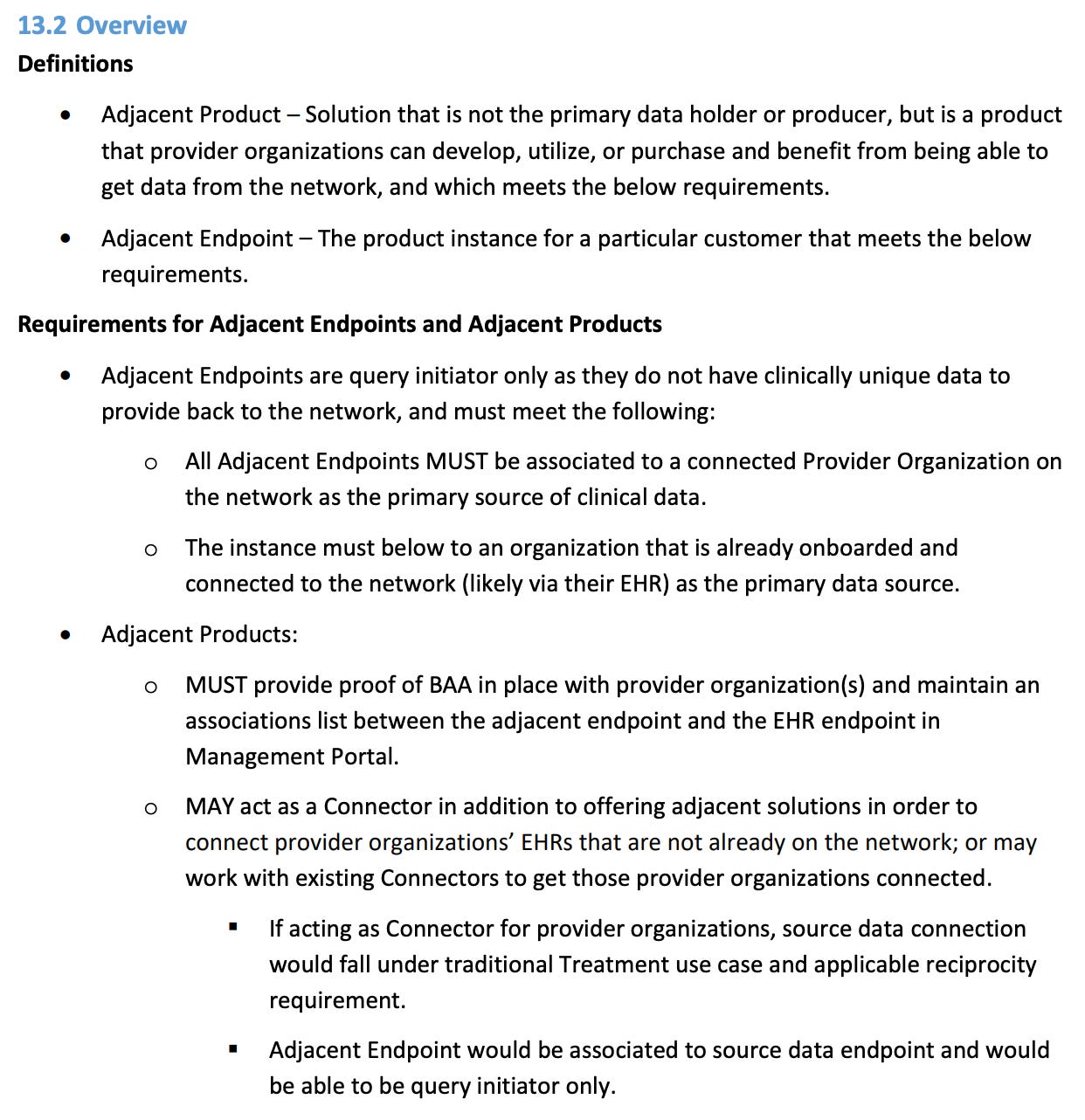

As on-ramps proliferated and access to the networks became an API call or embeddable UI widget away, the horde of non-EHR applications that a provider organization may purchase and use began to look hungrily at the data access available via the health information networks. These applications could technically join Carequality and Commonwell, but no special roles were defined in the networks. These applications were held to the same rules of purpose of use and Reciprocity as main entries - as software, they held no intrinsic rights to data and could only pull when involved in the care of a patient (Treatment) and when they contributed back the unique clinical data produced in their application as a byproduct of that care (Reciprocity).

This changed with the introduction of new roles, starting with Commonwell.

Adjacent Products

As noted earlier, the walls of Reciprocity did not fall with OBO - it began with Commonwell defining the Adjacent Product exception (page 67):

As noted in their definition, this new category of products was still a subcategory of Treatment. They specifically had a focus on care coordination:

Previous innovations and changes to network topology had largely been geared to reduce network congestion (gateways) or to expand the network to new participants (on-ramps). Both of these initiatives had upside - to improve network health and contributor growth, respectively. The value of the Adjacent Product role and similar categories on other networks, though, is less clear.

Firstly, as mentioned earlier, Reciprocity is a powerful concept for network health, acting as proof of treatment and reducing the number of net-negative nodes on the network. A node that is query-initiator only is at best dead weight and neutral to network health, but more often than not, acts as a pollutant - by contributing only query volume to the network, they only add strain on contributor infrastructure and the risk of privacy and security issues.

As we think about network topologies and incentives, maximizing Reciprocity is the best way to intrinsically grow the network. Any exceptions to Reciprocity defined by the networks should have a clear, dramatic upside to outweigh the costs. Furthermore, any nodes that want to utilize such exceptions should be held to the highest level of scrutiny.

Secondly, the industry should be wary of almost any application that claims to provide Treatment yet generates no unique data to contribute back to the patient's record. It is hard to imagine this large underserved cohort of provider software that is both Treatment and view-only. Only a handful of Treatment applications produce nothing - pure-play viewers of data generally don’t solve problems or fit well into integrated treatment workflows. Any application that claims to be providing Treatment and does anything of note produces some unique data that belongs in the longitudinal record. As noted in “The Gang Explains Information Blocking: HIPAA”:

In HIPAA's eyes, "your data" was prescriptively defined as the Designated Record Set, a (exceedingly broad) subset of all protected health information (PHI) that a patient might have access to.

Care coordination applications have care coordinator notes, tasks, phone calls, or a variety of other things. If these notes are used to make decisions about the individual's care, treatment, or payment, guess what? They are considered part of the DRS.

One thing I liked, though, was the rigor of the definitions and the process associated with Adjacent Products: how tightly they bound it to Treatment, the requirement for the main endpoint of the provider organization to be live already, and specifically limiting the exception to Care Coordination. This limits the usage of this designation, which is appropriate - it should be a rare occurrence, given the limited upside for network health and that few true Treatment applications actually qualify.

On Behalf Of

After Adjacent Products were announced by Commonwell, Carequality followed suit with a similar exception, On Behalf Of in August 2023:

At first blush, this definition is very similar - it allows ancillary applications to act as Query Initiators only. It has a few notable differences, though:

Breadth - Gone are the references to Care Coordination. Now this exception can be used by any application, so long as it has no new clinical information.

Discreteness - The connection to the responding node is not discrete, but instead through the formatting of the name. In some cases, the name does not clearly distinguish both the provider organization and software involved.

Loose Tie to Treatment - Even though the section is subordinate to Treatment, the paragraph is not as clear as Adjacent Products that the OBO application should be a Treatment application.

Self-attestation - The process does not ask for the submission of a Business Associate Agreement or require the main entry to validate the submission.

The end result of this is that the OBO exception becomes a much vaguer, more appealing offering with the same limited upside and large downside risks of Adjacent Products. As none of these nodes contribute back to the network, the best case scenario is that they are neutral to the network, adding dead weight but increasing physician satisfaction. The worst case is that their behaviors and the added burden of their volume cause network participants to leave. For the same reasons as Adjacent Products, the OBO exception should be a rare occurrence.

However, one positive of the way the OBO exception was defined is that existing OBO entries are easy to identify in the directory with Carequality’s Active Sites tool. Using that, we see there are over 1,000 On Behalf Of nodes today. OBO is not an infrequent event, meaning the network is increasingly saddled with non-contributing nodes that add complexity and potential instability without providing corresponding benefits to the overall system.

The OBO Workaround

The bigger problem with OBO is that creative participants in these networks have read the bylaw to also mean Treatment is not required. While the guide is very clear that the exception is to full participation (i.e. responding), there’s a strong belief in the market that if a health system waves the magic wand, the OBO exception can turn analytics, marketing, operations, legal, clinical trials, or other use cases into treatment.

Are accountable care organizations improving quality and analyzing utilization providing treatment and able to use OBO?

Is a health information management department releasing data to outside requestors providing treatment and able to use OBO?

Are tools to optimize health system financial performance providing treatment and able to use OBO?

Are value-based care contracting tools providing treatment and able to use OBO?

All these questions and grey areas remain somewhat vague and nebulous in the ecosystem today, so in absence of clear network policy, at least some interpret the answer to be “yes” here. More importantly, with no contribution or accountability via Reciprocity, any application that wants access to the health data of the entire country simply has to find the lowest common denominator provider organization and implementer to partner with, regardless of what they are actually doing.

Pulling the string further, organizations are able to combine the OBO workaround with the secondary use workaround detailed in “Epic v. Particle 2: The Problem of Secondary Use”. After pulling the data via OBO, the companies are free to use secondary use principles to share it however they please. Organizations can share with whoever they want, for whatever purpose they want, provided they don’t break the law in terms of consent. This creates a massive loophole in governance and data protection mechanisms.

While both workarounds are seemingly legal and not disallowed by network rules today, some argue that the combination of broadly interpreting OBO exceptions and leveraging secondary use principles effectively bypasses the current scope and intended safeguards of the network. This situation raises several critical concerns:

Data Privacy and Security: Patient data may be exposed to uses far beyond what was originally intended or consented to.

Network Integrity: The original purpose of the network - to facilitate treatment-related data exchange - is being diluted.

Trust Erosion: As these practices become known, it could erode trust among network participants and patients.

Competitive Advantage: Organizations exploiting these loopholes may gain unfair advantages in data access and utilization.

Even a handful of organizations that follow this pattern act as extreme pollutants to network health given their risk and the resentment they breed. These nodes set the networks on a path of stagnant network growth and open up the possibility of outright network decline - it is not infeasible at this point to imagine groups leaving networks with such pollutants.

As a result, in the wake of the Particle v. Epic dispute, both Carequality and Commonwell have reportedly gotten much tougher in their reviews of OBO applicants. This is warranted. However, the best solution is further definition and outright reform of this exception, which is what we see with TEFCA.

TEFCA Delegates

The TEFCA Delegation of Authority is the latest attempt to allow ancillary applications a path to participation. We can check out the most important new terms that delineate the new roles:

Principal: a QHIN, Participant or Subparticipant that is acting as a Covered Entity, Government Health Care Entity, NHE Health Care Provider, a Public Health Authority, a government agency that makes a Government Benefits Determination, or an IAS Provider (as authorized by an Individual) when engaging in TEFCA Exchange.

First Tier Delegate: a QHIN, Participant, or Subparticipant that (i) is not acting as a Principal when initiating or Responding to a transaction via TEFCA Exchange and (ii) has a direct written agreement with a Principal authorizing the First Tier Delegate to initiate or Respond to transactions via TEFCA Exchange for or on behalf of the Principal. For purposes 3 SOP: Delegation of Authority © 2024 The Sequoia Project of this definition, a “written agreement” shall be deemed to include a documented grant of authority from a government agency.

Downstream Delegate: a QHIN, Participant, or Subparticipant that (i) is not acting as a Principal when initiating or Responding to a transaction via TEFCA Exchange and (ii) has a direct written agreement with a First Tier Delegate or another Downstream Delegate authorizing the respective Downstream Delegate to initiate or Respond to transactions via

TEFCA Exchange for or on behalf of a Principal. More plainly, this means:

Principal: This is the main actor in the system. It could be various types of healthcare-related entities like hospitals, government health agencies, or healthcare providers. They're the ones who have the primary authority to exchange health information through TEFCA.

First Tier Delegate: This is an organization that's not acting as a Principal, but has permission from a Principal to exchange information on their behalf. They have a direct written agreement with the Principal allowing them to do this.

Downstream Delegate: This is similar to a First Tier Delegate, but they're one step further removed. They have an agreement with either a First Tier Delegate or another Downstream Delegate (not directly with the Principal) to exchange information on behalf of the Principal. This allows delegates to chain authority from the principal.

Delegate - A more general term that includes both First Tier Delegates or Downstream Delegates.

As a fictional example of a situation where these new Delegate roles can be useful, we could have Sutter Health acting as a Participant under the Epic Nexus QHIN. They purchase a cardiology application that they want to authorize to pull data through TEFCA. This application is already listed as a Participant through Health Gorilla, another QHIN, but, as SaaS, has no intrinsic right to pull data given it is not a provider organization:

Permitted users for purposes of this SOP include QHINs, Participants, and Subparticipants that are Health Care Providers and their Delegates. This application now has a path to do so - as a Delegate (specifically a First Tier Delegate).

Sutter Health submits a Delegation Notice to their QHIN, Epic Nexus, who validates the submission. When that’s complete, Epic Nexus updates Sutter’s directory entry to list the cardiology application. The cardiology application can then query and respond to queries, listing Sutter Health as the Principal when doing so:

While this particular example is Treatment-specific and Commonwell’s “Adjacent Product” and Carequality’s “On Behalf of” were focused on Treatment purpose of use, a Principal can authorize a TEFCA Delegate for any exchange purpose the Principal conforms to. For example, health plans can have Delegates for Operations exchange purpose, but not for Treatment.

As a result, delegates must follow the requirements of the standard operating procedure specific to the exchange purpose(s) of their principal.

1. Delegated Requests MUST follow all requirements that apply to the Principal, as set forth in the Exchange Purposes (XPs) SOP or applicable XP Implementation SOP.

2. All Principals MUST meet the definition of Principal and have a Responding Node, unless it

meets one of the following exceptions:

a. It is hierarchically below a Responding Node for Document Retrieval where such Responding Node is sharing all Required Information from a downstream Participant or Subparticipant that would otherwise be provided by the Participant’s or Subparticipant’s Initiating Node, if the Initiating Node were a Responding Node;

b. It provides an Initiating Node Only Attestation to the QHIN, per the RCE Directory Service Requirements Policy SOP; or

c. It is exempted from required Responses pursuant to the XPs SOP.As seen above, the Delegation of Authority SOP points to the “RCE Directory Service Requirements Policy SOP” concerning the “Initiator Only” status for Delegates (TEFCA’s exceptions to the Reciprocity). While Adjacent Product and On Behalf Of were both exceptions to the Reciprocity requirements of Treatment purpose of use, TEFCA Delegate is a role, not an exception, and does not automatically entail an exception to Reciprocity.

For purposes of this Initiating Node Only Attestation, Designated Record Set has the meaning assigned to that term in 45 CFR §164.501 but applies to a Principal regardless of whether the Principal is a Covered Entity.

The Attesting Entity hereby attests that data obtained or created by the Initiating Node following the Initiating Node’s use of TEFCA’s Connectivity Services that becomes part of a Designated Record Set of [Principal Name] is shared with and maintained in [Name of Principal's Responding Node], which is a Responding Node.

The Attesting Entity MUST notify [QHIN] immediately in the event this

Attestation is no longer accurate or complete.So, reading between the lines, there are actually four varieties of delegates:

Normal Delegate: The application responds to incoming queries with the unique clinical data it produces

Delegate with a Gateway Responding: If they’re using a CDR model, someone else up the hierarchy is responding on their behalf. For instance, our cardiology application could be pushing their data up to Health Gorilla’s CDR.

Initiator Only - No unique data: If the application is sharing all data back to the principal, it can submit an “Initiating Node Only Attestation” so that it doesn’t have to respond. This is to reduce duplicated data on the network. In our example, the cardiology application is sharing back all unique clinical data it produces to Sutter Health’s EHR.

Initiator Only - No data produced: If the application doesn’t generate any data. in the designated record set, it can submit an “Initiating Node Only Attestation” so that it doesn’t have to respond

Summing things up, we see these rough parallels:

However, TEFCA’s approach addresses so many of the issues and concerns that Adjacent Products and OBO has opened up.

First, TEFCA Delegate directly addresses business associate applications holistically, with clear definition of relationships to their covered entity partners. As an app, I understand exactly how I should behave, regardless of whether or not I have data to respond with.

Secondly, TEFCA is much clearer than Carequality that there is no “magic wand” when acting as a Delegate. If you are a Delegate, you are bound by the rules of the exchange purpose you’re claiming in your queries.

Most importantly, TEFCA Delegate inherently reduces “Initiator Only - No data produced” to near zero. While there will be many Delegates, most will respond directly, through a gateway, or through their Principal. With Principal’s QHINs vetting each Authorization of Delegation to ensure that applications have no Designated Record Set data, very few applications should be in the “Initiator Only - No data produced” category. In the case that they are, they will be heavily reviewed and scrutinized, as they should be.

The overall net in terms of network value seems very positive:

Reciprocity: The clarity around delegate applications needing to contribute all DRS data will lead to more Reciprocity. We will have more applications as contributing nodes, increasing network effects

Transparency: The explicit linking of applications to the organization that actually has the right to query will be powerful in understanding external organizations. Transparency engenders trust when direct relationships or communication cannot.

Friction: The TEFCA Delegate process has more friction than OBO, given that the Principal has to submit the Initiating Node Only Attestation. This is a good thing, in that nodes that have lower upside and significant downside should be held to a higher standard. Business associate applications inherently have less to contribute to the network and have proven risks, so scrutiny and validation that they will not be dead weight or negative forces is reasonable.

So the announcement last week thatCarequality was aligning with TEFCA is a big deal, if for no other reason than this one line:

Incorporating TEFCA Delegate policies into our existing On-Behalf-Of policies to increase transparency and controls.

The announcement shows that Carequality recognizes both the current problems that OBO presents, but also the opportunity to fix the approach thoughtfully. They’re signaling with the announcement that they are finally leaning into and putting the policies in place for a graceful transition to TEFCA. As discussed in 2022’s “Pondering the Healthcare Orb” as TEFCA was announced:

There’s a large adoption gap between “live” and “ubiquitous”. There’s also a large operationalization gap between “live” and “easy” that stands in the way of the progress on the adoption gap. This leaves us with roughly three major possibilities here:

If onboarding sucks, the standards are dense, and certification is heavy-handed, 2022 might just be the year the Trusted Exchange Framework started, with a long road ahead to nationwide usage and reliability.

If it’s architected in such a way to address those concerns and cut over existing Carequality framework participants seamlessly, we’ll see more success.

Lastly, if we actually see regulatory sweeteners or penalties that move TEFCA from voluntary to incentivized, we could see a mad rush onto the network.

Will all Carequality Implementers (EHRs, HIEs, and other on-ramps) jump to prioritize becoming QHINs? Will the framework attract growth while in a pilot phase? How quickly can the ONC or CMS come up with a way to bend existing regulatory authority to get people to join? Lots of questions and few answers, so my default bet is the first option, simply because the onboarding does seem cumbersome, there’s still quite a bit to pilot and revise.

With this announcement, we are finally seeing point 2 become true. Combined with the artful ways the ASTP incentivizes TEFCA in HTI-1 and HTI-2 that play to point 3, Epic’s announcement seems like the beginning of the mad rush and transition.

Looking Ahead

It should be apparent through TEFCA’s new policies and other networks’ alignment efforts that the leaders of these initiatives are making changes to address potential network stagnancy and decline. While the updates of the past month represent tremendous progress towards a healthier and more expansive network serving a much wider variety of use cases, there are still some things I would love to see buttoned up or improved:

Delegate Categories

Above, I mention and show 4 categories of Delegate, but in reality, TEFCA only defines 3, with a single definition of “Initiator Only”. Splitting this out to discrete categories seems necessary so that applications broadcast where other organizations can find their data if pushing to their principal or to have them say definitively that they do not produce DRS data.

Once these two subcategories of “Initiator Only” are delineated, the RCE and QHINs should periodically re-evaluate these applications. Over time, applications change and look to provide more value than view-only functionalities can through deeper workflow steps, which results in the creation of DRS data.

Ending Secondary Use Abuse

The secondary use workaround still feels like a looming problem for TEFCA. It’s not clear to me whether applications that want to resell the network’s data are prevented from spinning up or faking a lightweight provider organization to pull data and repackage it for their real primary exchange purposes. The definition of TEFCA Information suggests that this workaround is still available:

Now that the door is largely shut on the OBO workaround, it feels critical to focus on this big, hairy problem. Scaling the newly paved paths of Individual Access Services and Operations to all providers and payers will help by offering sanctioned alternatives for non-HIPAA entities and payers respectively. They can also continue to define paved paths for other underserved use cases. Beyond that, TEFCA will need to tackle the pseudo-provider playbook head-on, calling it out in their bylaws or otherwise publicly announcing their policies to prevent secondary use abuse.

As mentioned in previously articles, precluding “Initiator Only” applications from secondary use is a logical policy to consider. If they truly do not act upon or update the Designated Record Set and contribute nothing back to the network, their use of network data should be constrained to the specific primary exchange purpose. This further encourages reciprocity while still allowing a constrained path for “view only” ancillary applications.

Public Directory

TEFCA currently lacks the baseline transparency that Carequality has regarding the organizational directory. At a bare minimum, an equivalent tool to the Carequality Active Sites page. It’s in TEFCA’s best interest to do so, as such a tool would allow organizations to understand which of their trading partners are live, creating positive network effects and growth. As Individual Access Services is rolled out, patients also would benefit from a way to understand if they can use an IAS application to access their data.

Improved Directory Transparency

TEFCA should go further, though. The directory should publicly include salient information like nodes’ QHINs, status as a principal or delegate, claimed exchange purposes, and overall details about what they do will build trust. This level of transparency may seem radical, but by removing information asymmetry, we remove the ability for groups to take advantage of other organizations or patients. Patients deserve the ability to corroborate their own experiences with provider, payer, and individual access applications with the public statements to TEFCA from those same groups.

Something that is absolutely preposterous but often forgotten in the design of these networks is that Treatment queries are free of fees. The use of TEFCA to pull an aggregate, longitudinal patient record is an incredible superpower given no financial cost. With great power comes great responsibility, so an exceedingly high level of transparency is a truly fair price to be paid.

Reciprocity Incentives

It’s worth noting that other ubiquitous networks have rules and incentive structures akin to Reciprocity. In particular, the credit card networks have data levels, where merchants can share back increasing depth of purchase data for lower interchange rates. This incentivizes a sort of Reciprocity: higher-volume merchants look to improve margins by lowering their interchange rate. By sharing more data on purchases, they reduce the risk they impose on the network, ensuring the higher volume they bring includes fewer pollutants. It’s a very nifty virtuous cycle that’s worked quite well in terms of network health.

We should be creative in ways we galvanize organizations in TEFCA to be contributing members, reduce pollutants, and make the network stronger. Perhaps some future functionalities of TEFCA are only available to organizations that contribute data. The RCE or QHINs could hold non-contributing nodes to a higher fee schedule - given they entail higher risk and lower value to the network, an increase in financial contribution makes sense. Similar to the example of credit card networks and data levels, one could even imagine a similar pattern here, where there is a sliding scale of fees based on data contributed back.

Conclusion

With TEFCA, we can build something that no other country has dreamed of, reducing waste and improving care with the unprecedented efficiency and coordination of a fully connected, national digital health system. However, we can just as easily fail. The incredible capabilities offered by a ubiquitous health data network are only possible by a relentless focus on the health and value of that network, rewarding contributors and removing pollutants. If nothing else, TEFCA needs to be an even playing field that cannot be gamed or manipulated by any particular stakeholder or group. Absolute transparency enables this. Deep scrutiny of applicants safeguards this. Rigorous ongoing policing and regular third-party audits maintain this. The policies of the networks we build always need to be considered in the framework of network health - encouraging network growth and contributions, pruning groups that do not add value, and building toward a comprehensive ecosystem that serves all.

A big thank you to Garrett Rhodes and Colin Keeler for reviewing and editing.

Excellent piece. Thank you for taking the time and in sharing.

So where does the current interoperability spacial environment exist? I'd like to possibly align with them strategically

Kristin

Kmr@demosophy.com

Thanks for the very interesting article. OBO requests can raise significant legal issues for providers that produce PHI in response. If the requestor does not follow the HIPAA definition of Treatment, is a response also a data breach that must be reported?