The Gang Explains Information Blocking: HIPAA

You can’t escape it; you can only hope to contain it (with HITRUST)

I know it’s pretty evident given the immense schooling and large respect we give to lawyers, but the law is really complex. It’s humanity’s attempt to bind us to common understanding by sheer force of words and volume of prior art layered with incomprehensible jargon that puts healthcare’s oft-ridiculed acronyms and verbiage to shame.

It’s necessary, it’s important, it’s the bedrock of modern civilization but good god, it is a complete and utter pain for the bulk of the population. To wade through and try to parse even the simplest of terms and conditions is a soul-sucking, mind-numbing effort that leaves your author feeling like Charlie Kelly in the mailroom hunting Pepe Silvia.

Unfortunately for us, we work in a historically heavily regulated industry that is only increasing in its volume of laws and regulations as healthcare costs skyrocket and technology privacy abuses dominate headlines. It’s a great time to be an advocate, counselor, or barrister; it’s a bad time to jump in and try to grok every hoop and hurdle that must be overcome. As an entrepreneur, founder, PM, or operator, there’s a laundry list of acronymic regulations flying at us that change what we could do into what we must do.

Since laws (and, maybe more importantly, the resulting administrative process) are inherently pretty confusing, we should start with a few definitions, as the various pieces are often mistaken for one another. It starts when Congress in its infinite wisdom passes legislation, as it is intended to do (although how well is much debated). Well-written law designates responsibility to a federal agency (or creates a new agency) to fill in the details of the legislation’s typically broad strokes. The agency then begins a rule-making process to create regulations (a/k/a implementation) with rules (a/k/a the steps of the regulations). Entities affected by these regulations’ rules interpret what they must do and enact organizational policy. Subsequently, the agency follows up from time to time with non-binding guidance (a/k/a advice to entities who have expressed confusion or skirted the meaning of the regulation).

One such regulation has, after some delay, come into effect (as of April 1, 2021) that’s quite the doozy: information blocking. At face value, it’s something that no one can complain about - that actors in healthcare should not block the flow of health information. Compared with other important pieces of health tech regulatory history, it’s the type of regulation that’s more abstract and requires interpretation, rather than a prescriptive set of requirements like companion API requirements in ONC Cures Final Rule or the bulk of Meaningful Use 2. Most damningly, it’s a piece of regulation that a sizable cohort of people intentionally or unintentionally are misinterpreting to fit their own goals and needs.

So let’s try to make it easier (or at least as simple as boiling hundreds of thousands of words of legislation and regulation can be)! Read on below to get a brief and summarized history of some relevant healthcare technology legislation, a breakdown of the intent and actual function of ONC Cures’ information blocking provisions, and a perspective on where we might go next.

Unfortunately, to explain information blocking, we can’t just jump to the now. It requires the context and understanding of the US healthcare’s regulatory granddaddy, the OG, that nexus event where it all began. There’s a saying1 in digital health: “All roads lead to HIPAA.” Our story is no different.

HIPAA

HIPAA’s original intent is spelled out in its title: Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Its legacy in terms of popular awareness and outcomes is far different, but when it was proposed, our senators just wanted people to be able to take their health insurance between employers and to protect their insurance when workers were between jobs. That intent was neatly packaged up into the section of HIPAA called Title I: Health Care Access, Portability, and Renewability.

Despite it being front and center in HIPAA’s name, Title I concerning health insurance portability is not why anyone knows HIPAA today. As with most laws, senators tacked on all sorts of other initiatives. Frankly, though, no one cares about Title III (created the MSA, a now-obsolete precursor to the HSA), IV (group health plan requirements), or V (tax stuff for life insurance in niche scenarios) either.

It’s Title II that’s the true focal point today: Preventing Health Care Fraud and Abuse; Administrative Simplification; Medical Liability Reform. Title II is, simply put, loaded, but roughly can be broken out into a few subsections:

Transactions and Code Sets Rule

Privacy Rule

Security Rule

Transactions and Code Sets Rule

This part is simple. Our legislators saw the possibility of proprietary vendor formats spiraling out of control and stepped in to choose standard ones (X12 and NCPDP). In doing so, this simultaneously would prevent the potential burden on providers of grappling with those many formats and also accelerate the adoption of electronic exchange. Touche, Congress, two birds, one stone.

In retrospect, while wildly successful in their ubiquity, we now look back on these standards and wish they were less set in stone. X12 feels outdated and even though NCPDP has iterated, it’s still a gross closed standard in an era of open documentation and JSON. Iteration and change are part of the human experience, but these standards continue to live in the past.

Privacy Rule

While the other rules are notable, this is the moneymaker. If some malcontent is tweeting about “HIPPA”, it’s the Privacy Rule they’re misspelling. If you have a psychopath yelling at the Delta flight attendant for asking about his vaccination status, it’s the Privacy Rule he’s misinterpreting. And as we think foundationally about ONC Cures Final Rule and the information blocking within, it’s the Privacy Rule we need to start with.

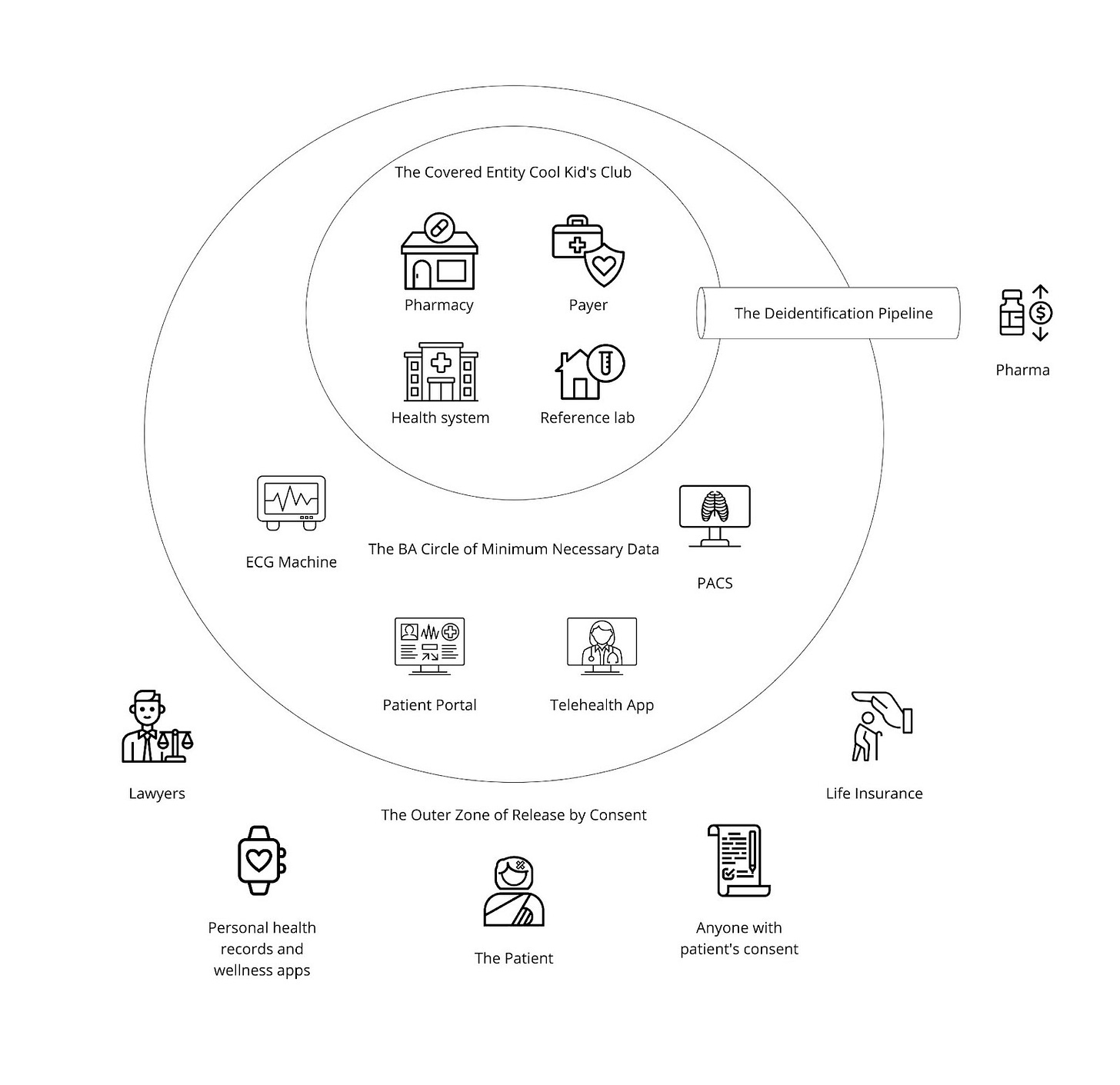

The Privacy Rule, if summarized, is fairly intuitive. It nicely circled the main organizations that are directly involved in the delivery of or payment for patient care (providers, payers, clearinghouses) into a group (a/k/a The Covered Entity Cool Kids Club) and said “it’s really important that you all, who I will call covered entities, are able to share information about a patient, so you don’t need explicit consent.” It’s fairly logical and desirable that covered entities have low friction in sharing what’s necessary to keep you healthy and pay for what keeps you healthy. If you imagine a hypothetical patient journey where you see your primary care provider one day, are hit by a bus and rushed to the local hospital emergency room, pick up a variety of medications from your local pharmacy after discharge, and get an explanation of benefits from your insurer stating how you owe nothing since they’ve paid for all that care (lol, can you imagine), your patient data should flow seamlessly, without manual intervention by you for each step. Defining Covered Entities is what enables this, at least hypothetically.

Brief day job interlude: Covered entities (specifically digital health companies that are covered entities) is where Zus is focusing a lot of our efforts, in that we think creating tools for this class of company to build best-in-class patient and provider experiences is mission critical to better healthcare in America. If you’d be interested to join that mission, we’re hiring for a ton of roles! If you’re that class of digital health startup, let’s talk!

The Privacy Rule then circled another group, the BAA Circle of Minimum Necessary Data - organizations that provide services for covered entities and receive patient information as a result of those services - and said “you all, business associates, are doing good things for these care organizations, but you should only have the minimum amount of information necessary to do those good things.” Again, this is super logical. If I’m an accountant for a healthcare organization, I should only have the patient information that is needed for accounting, not detailed surgery records or advanced vitals. Historically, it may be possible to skirt by as a software vendor if you were selling programs and applications installed on-premise with no PHI access to that vendor’s staff. Increasingly, though, as the supplementary software sold to hospitals, clinics, and other covered entities is cloud-based, the vendors are certainly providing services and therefore are subject to Business Associate Agreements (BAAs). It is difficult to sell software to covered entities and not sign a BAA today.

Outside of these bubbles is you, the patient, as well as non-covered entity organizations who do not provide services to the covered entity (but may want or need health data). You may occasionally want to have your health records or want to share your health records with those other organizations outside the bubble. Luckily, the Privacy Rule addresses this by giving you that explicit right - with your authorization, you can get your data and provide it to whomever you want. This is great for your own record keeping, as well as more practical scenarios like underwriting life insurance or advancing legal proceedings.

In HIPAA's eyes, "your data" was prescriptively defined as the Designated Record Set, a (exceedingly broad) subset of all protected health information (PHI) that a patient might have access to. This subset, defined here, is summarized as a covered entity’s records about a patient that are either medical and billing records at a provider, any records used in the claims or case management process at a payer, or any records used to make a decision about a patient. The HHS’s explanation here is excellent, with many examples of what’s in and not in the designated record set.

Info in the Designated Record Set

Medical records

Billing and payment records

Insurance information

Clinical laboratory test reports

X-rays

Wellness and disease management program information

Notes (aside from behavioral health)

Note that these records may live in many systems across the covered entity! This means that upon request, it’s not just the EHR that needs to be equipped to help covered entities respond to this request - all systems that contain unique information used to make a decision about a patient must be reviewed and information gathered.

In terms of what’s not in the Designated Record Set, it can largely be broken down into “summary style information that contains PHI”, “behavioral health information”, and “information for legal proceedings”:

Info not in the Designated Record Set

Quality assessment or improvement records

Patient safety activity records

Business planning, development, and management records that are used for organizational decisions and not decisions about individuals

Peer review files

Practitioner or provider performance evaluations

Customer service quality controls

Formulary development records

Psychotherapy notes

Information about the individual compiled in reasonable anticipation of, or for use in, a legal proceeding

One last fun nuance here: the DRS exists as a lower bound, not an upper limit or ceiling. The covered entity has every right to use its discretion to go beyond the designated record set and share all information that ties to the patient record. So if a patient asks for the records, a provider (depending on state law) could possibly release psychotherapy notes but is not required to do so.

Consented sharing is not the only way non-covered entity organizations can gain access to health information, though (of course there’s a loophole). HIPAA explicitly calls out that if protected health information is de-identified (stripped of any and all identifying information such as MRNs, member numbers, and demographics) up to a defined standard, it is no longer PHI and therefore not subject to the Privacy Rule anymore. This De-identification Pipeline allows de-identified data to be shared in a very free and open fashion, which has led to the rise of private data networks such as Datavant, Health Verity, and IQVIA that intermediate between data holders (health systems, generally) and data recipients (pharma, generally).

Altogether, you end up with a health technology universe that looks something like this:

Overall, I think the intent of the Privacy Rule is clear and honestly straightforward:

Make it easy for all the different types of organizations providing care or paying for care to share a patient’s record. I hate typing in my medical history as much as the next person. Everyone can get behind that.

Allow for organizations that provide services or build tools to help care providers or payers to provide their value while limiting their security and privacy impact. Totally reasonable to try and prevent abuse.

Give patients a super clear path to pull their data outside of HIPAA and provide it to whomever they want. Identity fraud is real but patients are better served when they can get their information.

Notably, HIPAA has come up a lot in these turbulent pandemic times, so let’s cut to the chase. The law says absolutely nothing about businesses and organizations living in the Outer Zone of Release by Consent, such as sports stadiums, airlines, your employer, or your random neighborhood bakery. They are free to ask their potential customers whatever questions they want and are not under any HIPAA regulations. Dak Prescott is an idiot and I’m not just saying that because I’m from Philly. Hence the fun sarcastic Twitter memes going around recently:

Security Rule

The Security Rule is a super generalized set of guidelines about administrative, physical, and technical safeguards for a subset of PHI: electronic PHI. The intent is clear - our legislators wanted covered entities and their business associates to be best-in-class in regards to information security. This is kinda bonkers - Dr. Smith’s office in small-town Kansas will never be an exemplar for InfoSec - so the government sorta recognized this in the law by giving some flexibility on non-required specifications.

However, given how vague it is in letting covered entities define their safeguards, it left a lot of handwaviness. When HIPAA compliance means many different things to different people all at the same time, it means nothing at all. With the rules unclear, but the penalties possibly crippling, people naturally sought certainty. Thus, the HITRUST certification was born by necessity after 11 years of the industry struggling. To standardize and simplify the compliance experience is inherently valuable to avoid the difficulty of understanding the thousands of permutations of differing circumstances. By completing HITRUST, like SOC 2 or many other compliance certifications, a company attests to standard sets of measures to ensure security. Adherence to a standard builds trust between parties without lengthy back-and-forth negotiation custom to each institutions’ processes, ultimately simplifying contracting. While this same process happens in other industries simply due to a desire for simple security, HIPAA causes it to be accentuated and accelerated to a level not seen elsewhere (except perhaps in banking). What’s especially noteworthy (and often overlooked) is that HITRUST is not an officially recognized certification and does not mean the government will give you a pass if there’s a breach.

Anyway, all that aside, that’s HIPAA. It fundamentally defines healthcare and shapes the way we relate to one another, sell products, and connect systems. While the Privacy Rule clearly outlines how data sharing practices should happen between actors, the Security Rule heavily incentivizes them to be cagey with their data. Most of the pain felt today with interoperability and integration stems in some way from the roles and responsibilities implicit via HIPAA. In fact, if you look closely, the three zones closely correspond to the three divisions of digital health I outlined in A Song of Health and FHIR:

So yeah, that’s HIPAA. A couple of key points to remember:

HIPAA’s title is about Health Insurance Portability, even though we remember it for Health Information Privacy

You’re either a Covered Entity, a Business Associate, or a non-HIPAA entity

Covered Entities are providers, payers, and clearinghouses. They can exchange patient data freely without explicit consent for permitted purposes

Business Associates do things for Covered Entities and therefore are allowed to get some data (the minimum necessary) without explicit consent to do those things

Patients or other non-HIPAA entities who want health data are entitled to receive those health records (the Designated Record Set) with explicit patient authorization

I hate to go all Denis Villanueve on you here, but we’re clocking in now at nearly 2500 words, so this concludes Part 1 on our journey to understand the twists and turns leading us to information blocking and the regulatory policy of today.

Luckily for you, the similarities to Dune end with the equally high production value, substantially sized audiences, and attractive leading man – Part 2 is already ready, so it’ll be dropping sometime in the next few days.

Huge shout out to the squad of friends, colleagues, and Good Samaritans who contributed by editing this article - Colin Keeler (check out Atai if you think mental health could be transformed by psychedelic compounds), Garrett Rhodes (Redox is dope and their new payer offerings are sweet), Samir Jain (serial health tech legend, currently of RubiconMD), Ed Manzi (former law student building something new in home medical equipment), Matthew Fisher (actual lawyer at Carium, a virtual care platform company, and host of Healthcare de Jure), and Joshua Schwartz (PM at Commure). It takes a village to navigate the legal norms we impose upon ourselves as a society, so appreciate their help.

There is no such saying, but it would be a lot cooler if there was.