Pondering the Health Policy Orb

Travel travel and fortune telling about healthcare's biggest regulatory deadlines and due dates in 2022

Apologies for the double send - email length was too long, so here’s the real version.

‘Tis the season. As we work our way through the holiday calendar and into the new year, we are assaulted with a barrage of retrospectives and prognostications, looking back on what has happened and what may come. These are fun at their best (Nikhil’s is straight 🔥 as always), but frequently veer into self-indulgence too vague to outline real opportunities, guide any action, or affect any change.

Luckily for us, we don’t need a crystal ball or a consultation with the Oracle to understand where we’re going, at least in regards to this newsletter. This coming year has a lot of regulatory measures finally coming to fruition in terms of hard dates or expected guidance. I know we’ve talked a lot about regulation lately, but there are huge opportunities to be realized buried in each of these.

ONC

ONC Cures Rule

The ONC Cures rule stipulations continue to come into effect. While the first set of information blocking provisions of this past year made some noise, it’s actually 2022 where we see the money makers become required.

FHIR APIs

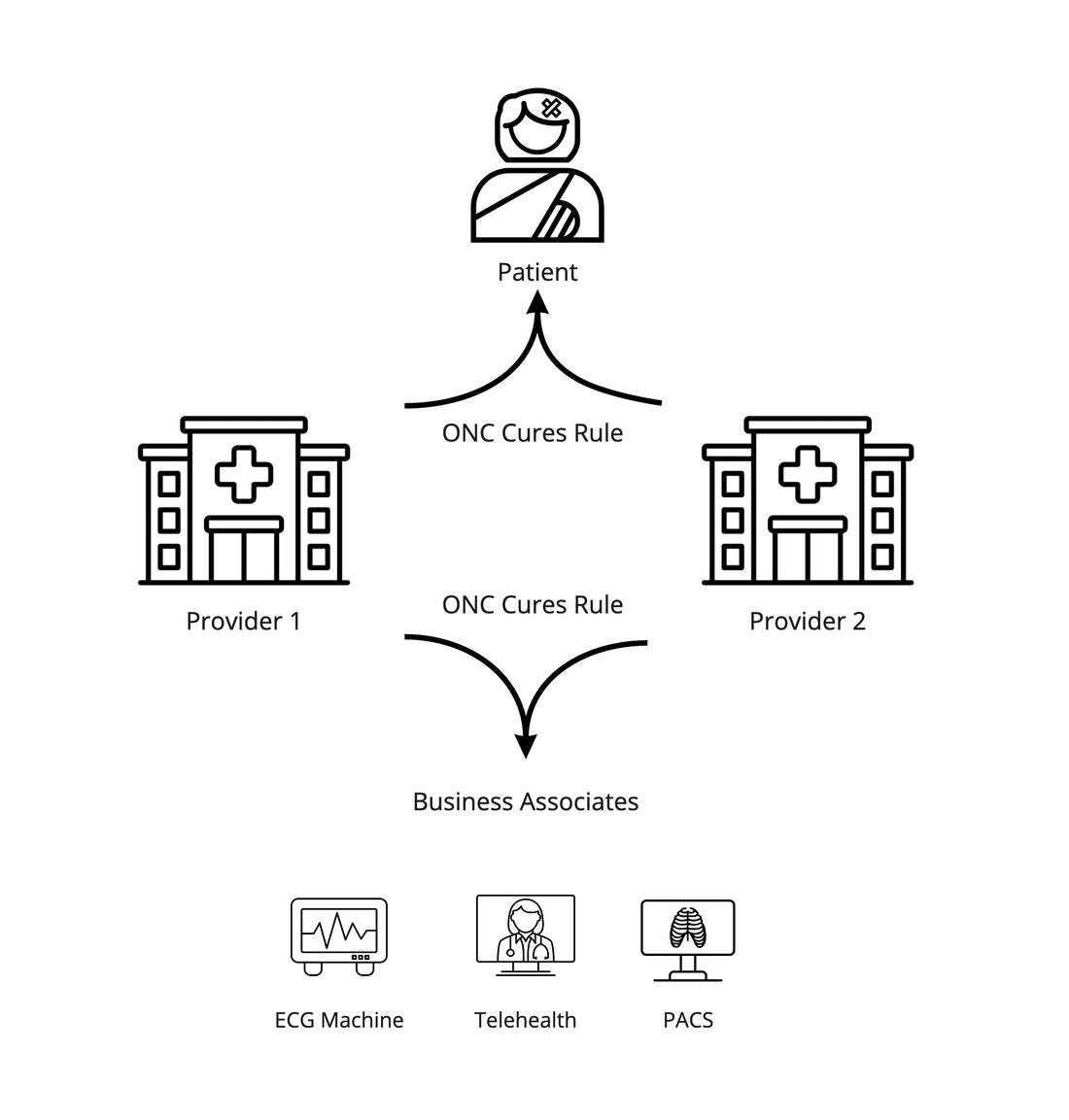

As mentioned in the Cures article, the EHR certification criteria bring to bear a set of net-new EHR capabilities we should be pumped about:

…some special nuggets that do create (via new requirements) some EHR capabilities for Business Associate applications to play with via the EHR Certification Updates: the population API bulk APIs and the standardized patient-level APIs.

Given the deadline isn’t until the end of the year (and given that a number of vendors will inevitably fail their first pass or two at the criteria), we can’t expect these functionalities to be uniformly deployed this year, but we certainly can expect roll-out by some of the leading EHRs. We’re already seeing the FHIR programs of Epic and Cerner essentially cover most of the criteria, but we can reasonably expect athenahealth, Allscripts, and Meditech to upgrade and open up their FHIR programs this year.

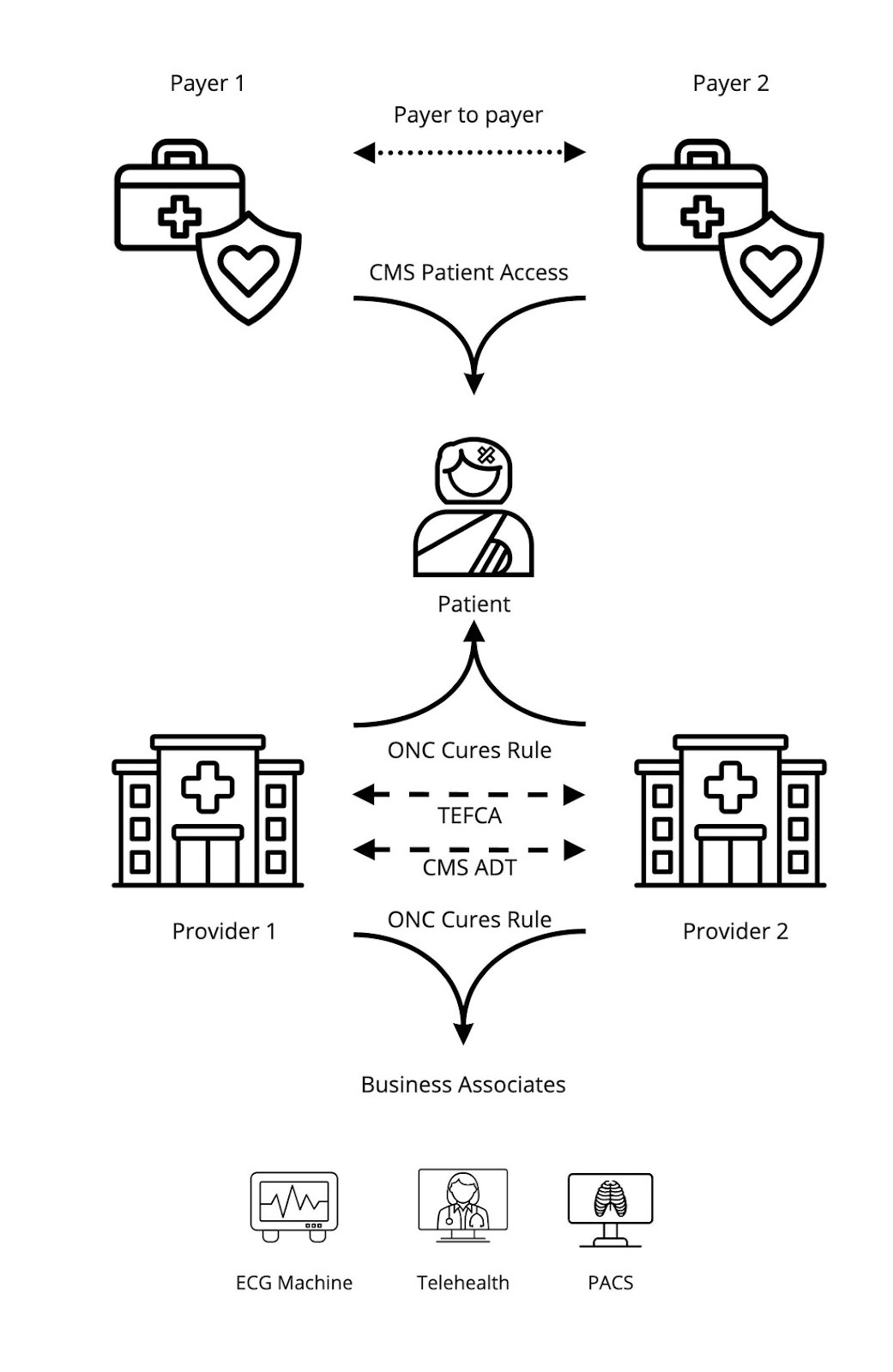

With this, we can start to sketch out what the overall API ecosystem looks like:

EHI Deadline

On the information blocking front, we’ll see the definition of Electronic Health Information (EHI) expand from just the USCDI dataset to everything in the Designated Record Set.

The biggest thing to keep an eye on is the timing gap between the policy aspect (the information blocking update) and the technical aspect (the EHI Export capability). The latter is an EHR certification criterion but is not applicable until 36 months after the rule was finalized. So it will be interesting to watch how provider organizations handle the updated information blocking provisions for those 15 months in 2022 and 2023 during which their EHR vendors are not required yet to have created the correlated EHI export functionality.

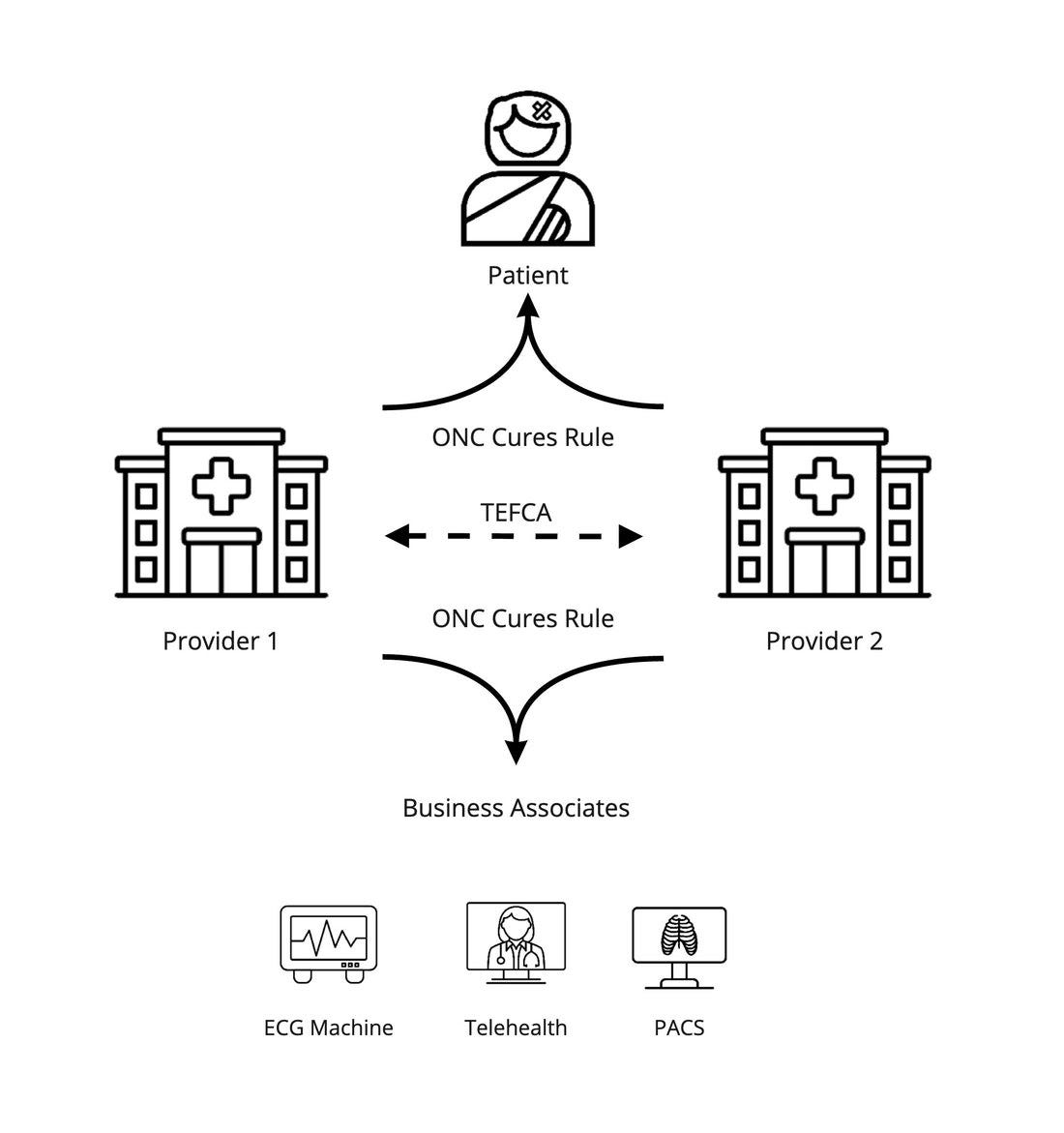

TEFCA

2022 is the year the Trusted Exchange Framework finally becomes real. Kinda. Sorta. Maybe.

As noted in The Gang Explains Cures:

On the positive side, TEFCA continues to rumble forward now under the Biden administration, so there’s some possibility it actually comes to fruition. On the less positive side, it’s still a voluntary new framework, so it’s unclear what adoption will look like, especially if the onboarding and certification processes end up being heavy.

There’s a large adoption gap between “live” and “ubiquitous”. There’s also a large operationalization gap between “live” and “easy” that stands in the way of the progress on the adoption gap. This leaves us with roughly three major possibilities here:

If onboarding sucks, the standards are dense, and certification is heavy-handed, 2022 might just be the year the Trusted Exchange Framework started, with a long road ahead to nationwide usage and reliability.

If it’s architected in such a way to address those concerns and cut over existing Carequality framework participants seamlessly, we’ll see more success.

Lastly, if we actually see regulatory sweeteners or penalties that move TEFCA from voluntary to incentivized, we could see a mad rush onto the network.

Will all Carequality Implementers (EHRs, HIEs, and other on-ramps) jump to prioritize becoming QHINs? Will the framework attract growth while in a pilot phase? How quickly can the ONC or CMS come up with a way to bend existing regulatory authority to get people to join? Lots of questions and few answers, so my default bet is the first option, simply because the onboarding does seem cumbersome, there’s still quite a bit to pilot and revise.

As TEFCA comes into effect, we see an information landscape like this (dotted line to portray the voluntary/optional nature of TEFCA, as well as the fact that it uses old XML standards):

USCDI and USCDI+

As a refresher, the United States Core Data for Interoperability (USCDI) is the ONC’s standardized set of health data classes and constituent data elements for nationwide, interoperable health information exchange. It’s the heir apparent to CCDS, C-CDA, and other dataset/content standards (detailed more in this article).

The ONC wisely built in a mechanism to iterate and version USCDI, so that they could move the needle on what’s included in this core data forward without additional rule-making. We saw a very modest and iterative second version get dropped in 2021 with 3 new data classes and a number small additions to existing classes:

These elements are great to add, but were already generally included in the C-CDAs that have been exchanged for a decade, meaning we’re just edging our way back to parity there. We’ll see another version in 2022, but the question will be if and how it actually moves the needle. I’d like to see actual progress this time. This part of my comment from last year still encapsulates my view:

We strongly believe that to increase the value of USCDI to healthy but unengaged patients, core administrative data is among the most important to define and expose, such as the aforementioned Appointment information. Additionally, Insurance (defined in Level 2), Advanced Directives (Level 1), Referral (comment), additional patient demographics (multiple levels) and financial information are core to the patient experience and have the greatest potential to increase patient engagement in healthcare activities once exposed, aggregated and understood.

We strongly believe that to increase the value of USCDI to the sickest, most chronic patients, specialty-specific data is also among the most important to define and expose, such as the Ophthalmic Data (Level 2), pregnancy/obstetrics data (comment under Observation), and oncology data (comment under Observation)

I’m not holding my breath for something revolutionary with this version. Insurance has a decent chance of inclusion, but the Level 1 and comment level data seem more far-fetched. It’s also hard to align the growth of USCDI (which is core data by definition) with niche specialty data, no matter how valuable for a select subset of patients. In any case, the USCDI versioning process doesn’t seem likely to effect large change in 2022, but is worth watching as we get into spring time.

However, the ONC pulled an interesting, slightly random move late in 2021, announcing the USCDI+ initiative in order to:

…support the identification and establishment of domain or program-specific datasets that will operate as extensions to the existing USCDI.

This is interesting because it’s just vague enough that it could possibly solve the specialty dataset concern from above (woo hoo!). This is also slightly random, as the USCDI is not static and has a well-defined versioning process to extend itself. It’s almost as if ONC is conceding that USCDI and associated versioning is either too slow or not comprehensive enough to do what they want to do. It’s almost as if they felt held back or hamstrung by the well-defined process they created to outline interoperable data, so they tacked on the + as a personal license to kill unencumbered by existing rules.

Also, while tossing on that plus sign makes for a neat little title, it is also uniformly horrible for Googleability and general SEO.

USCDI+ is light on details thus far, so we should expect the full charter and use cases to come this year. Personally, I’m most interested to see what regulatory tie-ins it will have to actually add teeth and make sure vendors and providers use it.

CMS

The CMS created two rules (the CMS Interoperability and Patient Access Final Rule and the CMS Interoperability and Prior Authorization Proposed Rule) that were tied loosely to Cures Act principles and goals in 2020.

However, while some of the regulations came into effect in 2021, the CMS decided to forego the enforcement of one major provision and did not finalize the second rule. Could 2022 be the year that fixes that?

CMS Interoperability and Patient Access Rule

Bundled into the CMS Interoperability and Patient Access Final Rule were a few major initiatives:

Electronic patient event notifications (applicable May 1, 2021) - Make providers aware that the patient has received care elsewhere, improve post-discharge transitions and reduce the likelihood that a patient would face complications from inadequate follow-up care.

Patient Access APIs (applicable January 1, 2021, enforced July 1, 2021) - Ensure patients using third-party applications of their choice can access their adjudicated claims and other clinical data their payers may have through Patient Access APIs

Provider Directory API (applicable January 1, 2021, enforced July 1, 2021) - Promote public discovery and access of the provider networks that payers have via open APIs

Payer-to-payer data exchange (applicable January 1, 2022, but delayed enforcement indefinitely) - Cultivate coordination of care between payers by requiring payers to send a member’s data to another payer at the patient’s request

A lot of this was completed (or had hard deadlines) in 2021, mainly in May and June. Providers used a variety of technologies to meet the event notification requirement ranging from private vendors such as PatientPing or Collective Medical, local HIEs that supported event notification, or even the nationwide DirectTrust network. I’ll let Dhruv explain the positives of this rule:

Electronic patient event notifications rule have MASSIVE potential if harnessed and educated about correctly. Our Chief Medical Officer is super excited to leverage them. It's not just making providers aware that the patient has received care elsewhere. It's also that providers can compel hospitals to comply. They might say HL7v2 covers this, but that's really positive pressure for the hospital to stand something up OR give access to the ADTs via a state hospital association via a data use agreement.

On the other hand, while effective and exciting in some regards, it’s not perfect. The CMS rule was quite loose and flexible on both the content and transport standards, recommending the use of HL7v2 ADT (a legacy standard that just happens to be quite ubiquitous) but allowing for other methods. This meant that while all participating hospitals stood something up in regards to event notification, the overall sum of the work did not congeal into a uniform, accessible, and connected nationwide network. While there’s some value in regional networks, that’s a miss that I hope they correct in 2022. Mandating Patient Centered Data Home or a functional equivalent would stitch together the disparate networks and force vendor networks and HIEs to compete on functionality, not the little kingdoms of hospitals they’ve built and guard.

The Patient Access APIs, on the other hand, were a clear home run. The CMS gave great guidance on what modern standards to use and payers largely implemented on time this past summer. A number of vendors who jumped on this opportunity benefited - organizations like Smile CDR, Inovalon, 1up Health, and others created payer FHIR servers to ingest various data formats and expose the Patient access APIs, while Plaid-like hubs such as OneRecord, 1up Health, and Flexpa aggregated (or are working to aggregate) those endpoints to create greater accessibility to patients’ payer-maintained claims and clinical history.

The provider directory requirement landed somewhere in between. It was rolled out on time, which is good in terms of data access, but lacked some specificity in terms of how the API should be formatted. Given the rocket ship success in the past few years of provider directory players like Ribbon Health, it’ll be interesting to watch as they and others aggregate and utilize all these new data sources to level up their existing solutions.

Lastly, while the intent behind payer-to-payer data exchange would have been just as impactful and useful to the healthcare ecosystem as the other regulations, the CMS got walloped by the industry for not actually being prescriptive on how to accomplish that goal. In particular:

Transport - The CMS didn’t say how payers should send the data. It did not specify whether the transactions should be peer-to-peer or mediated by a patient (see some vigorous debate from early 2021 on the topic here).

Content Format - The CMS thought that it would ease implementation if the payers could just send the data in the original format they received or stored it.

Thus, in the CMS’s own words:

In the CMS Interoperability and Patient Access final rule, CMS did not require a specific mechanism for the payer-to-payer data exchange. Rather, CMS required impacted payers to receive data in whatever format it was sent and send data in the form and format it was received, which ultimately complicated implementation by requiring payers to accept data in different formats.

Since the rule was finalized in May 2020, multiple impacted payers have indicated to CMS that the lack of technical specifications for the payer-to-payer data exchange requirement is creating challenges for implementation, which may lead to differences in implementation across industry, poor data quality, operational challenges, and increased administrative burden. Differences in implementation approaches may create gaps in patient health information that conflict directly with the intended goal of interoperable payer-to-payer data exchange.

After listening to stakeholder concerns about implementing the payer-to-payer data exchange requirement and considering the potential for negative outcomes that impede, rather than support, interoperable payer-to-payer data exchange, CMS is exercising enforcement discretion to delay the payer-to-payer data exchange requirement until future rule-making is finalized.

So in 2022, will future rule-making be finalized? This author thinks and hopes so. My guess is that the future rule explicitly defines the data set and format to be exchanged as Common Payer Consumer Data Set (CPCDS) to align with Patient Access APIs (although there is some debate whether that’s appropriate) and the interactions as a subset of the DaVinci Payer Data Exchange (PDex) Implementation Guide.

In any case, most of the Patient Access Rule, aside from Patient Access APIs, should stand as a lesson learned for the CMS (and other agencies) to lean into prescriptive regulation for greater success.

As an aside: the requirements above only apply to a subset of payers with clear CMS authority - Medicare Advantage organizations, state Medicaid and CHIP FFS programs, Medicaid managed care plans, CHIP managed care entities, and QHP issuers on the FFEs. Commercial insurance plans are therefore exempt, so while this rule empowers patients, it’s interesting to think what the central overlap is in the Venn diagram of “users tech-savvy enough to use a third party application to aggregate payer data” and “members of an insurance plan that is CMS regulated”. I’d love to see ONC and CMS somehow find the authority to push this to apply to all payers in 2022.

CMS Prior Auth Proposed Rule

Prior authorization sucks. In order to control costs and direct members to effective care, insurance carriers gate access to different medications and procedures behind an approval process. Described by Olivia succinctly as the banality of evil, it’s an administrative process that somehow manages to both erode the payer-provider relationship while simultaneously worsening the member experience. As the CMS puts it:

…stakeholders have stated that diverse payer policies, provider workflow challenges, and technical barriers have created an environment in which the prior authorization process is a primary source of burden for both providers and payers, a major source of burnout for providers, and a health risk for patients when it causes their care to be delayed.

Although standards have existed practically since the dawn of time, it’s still an overwhelming analog, paper-based process. Per the data:

14 percent of the respondents indicated that they were using the adopted standard in a fully electronic way while 54 percent responded that they were conducting electronic prior authorization using web portals, Integrated Voice Response (IVR) and other options, and 33 percent were fully manual (phone, mail, fax, and email)

A number of vendors have popped up in the past few years attempting to offer solutions (ReferralMD, Myndshyft, PriorAuthNow, Cohere Health) but the free market doesn’t seem to have made a dent. Many payers don’t offer the right connectivity, so the vendors are stuck cobbling together and overlaying portals, fax, and other antiquated data exchange. Similarly, only the most advanced EHRs really conceptualize prior authorization in their software and support the right X12 standards for data transfer.

Seeing this problem, the CMS created the CMS Interoperability and Prior Authorization Proposed Rule, which tackles prior authorization, but also combines a number of prior interrelated initiatives:

Updated APIs

Patient Access APIs - Expand the Patient Access APIs to include pending and finalized prior authorization decisions

Provider Directory API - Update the provider directory APIs to use a standardized Implementation Guide, HL7 FHIR Da Vinci PDex Plan Net IG, in order to further standardize this data exchange.

Payer-to-payer data exchange - Actually define the content, transport, and patterns that payers should use for payer-to-payer exchange, righting some of the wrong of the Patient Access Rule.

Most of this seems good and likely to be lightly commented and rubber-stamped. Prior authorization data is actually more valuable to me as a patient than the second or third-hand clinical data I might get from payers. Giving more detailed guidance for the provider directory is also good.

I think payer-to-payer data exchange still needs some work and likely will be heavily revised. The rule details the use of a standard (FHIR) and two implementation guides (Bulk Data Access and Payer Coverage Decision Exchange), which is progress. Compared to the simple exchange of the Patient Access APIs (which many payers still struggled with), the payer coverage decision exchange is quite a complex pattern:

Simply put, I don’t know that I see this initiative being successful if this is the flow that hundreds of payers have to implement nationwide. It’s a somewhat obtuse and confusing multi-step process.

New APIs

Provider Access API - Ensure relevant data is available to providers at the point of care, allowing them to see their patient's claims history, available clinical data, and prior authorization decisions. CMS defines actually two APIs here: individual patient level and population level

Prior Authorization Documentation Lookup Requirement API - Allow providers to understand exactly what documentation needs to be submitted in order for their patients to be approved for the care the doctors are prescribing.

Prior Authorization Support API: Create a national network for prior authorizations that has not naturally arisen despite existing standards and efforts of private vendors

Suffice to say, CMS went ham, likely because it was December 2020 and there would potentially be turnover as administrations changed. In that way, I can appreciate their hustle to get the tail-end of their agenda out the door.

All three of these net new initiatives are meant to advance the exchange between providers and payers and reduce administrative burden. In contrast to the other APIs we’ve discussed, though, such exchange is actually uniquely burdened by the sins of prior regulation: the adoption of X12 via HIPAA, a topic I’ve ranted about before in Chasms and Fire. Because many transactions between providers and payers are mandated to use X12 from that 1996 law, the CMS is forced to sidestep, nuance, and hairsplit their way out of using X12:

The payer would make a PAS API available for providers. When a patient needs authorization for a service, the payer's PAS API would enable the provider, at the point of service, to send a request for an authorization. The API would send the request through an intermediary (such as a clearinghouse) that would convert it to a HIPAA compliant X12 278 request transaction for submission to the payer. It is also possible that the payer converts the request to a HIPAA compliant X12 278 transaction, and thus the payer acts as the intermediary. The payer would receive and process the request and include necessary information to send the response back to the provider through its intermediary, where the response would be transformed into a HIPAA compliant 278 response transaction. The response through the API would indicate whether the payer approves (and for how long), denies, or requests more information related to the prior authorization request, along with a reason for denial in the case of a denial.

What a convoluted configuration! I know X12 is in HIPAA, HIPAA is law, and law cannot be easily overridden by regulation. However, I'll say this bluntly: EDI (of which X12 is a subset) is a dense standards relic of the 70s, prone to errors, hidden behind a consortium's paywall to extract money from users while providing minimal value, and wrapped with equally ancient transport standards.

If the government believes we should use APIs for exchange, let's actually use APIs for exchange. Let's decouple the intent of the law from the execution of the law. Let's give the ONC and CMS authority to update the relevant standards as we move through generations of technology so we're not stuck in stone as a society.

Anyway, thus ends that mini-rant. The goals of the new APIs are noble and just, so we can respect that prerogative and soldier on despite some misgivings. The implementation guides in play are these DaVinci specs:

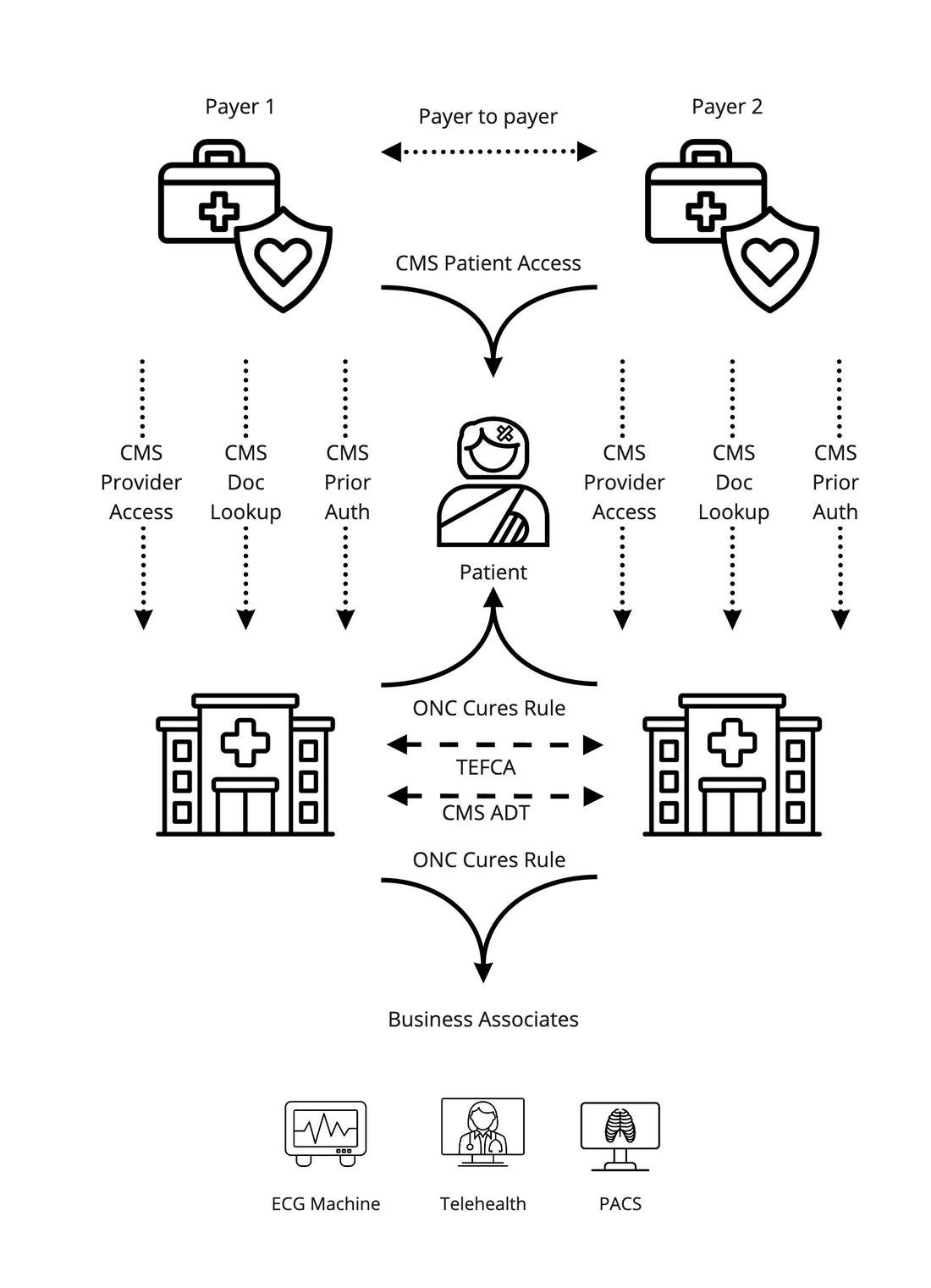

At a high level, those guides lead to an interchange that looks like this:

I gotta be frank, I’m not in love with this. For the coverage requirements and documentation templates, you’re asking payers (who vary a lot but typically aren’t the most technologically savvy organizations) to implement some of the rawest and least seen-in-the-wild parts of FHIR: Clinical Decision Support Hooks and CQL. On the actual prior authorization, you’re stuck transforming and mapping to that interim X12 format.

If this proposed rule is finalized as it’s written today, there will be large challenges ahead for payers. It’s one thing to standardize your claims and clinical content to FHIR and offer it via a simple REST API. It’s another to encode your business logic and rules for hundreds or thousands of conditions into these nascent standards and ensure that it works for tens of thousands of providers nationwide.

My guess about what we’ll see this year (and preference) is that we simplify and push CRD and DTR to a later phase. It’s not that I love the PAS (I clearly don’t from my diatribe about X12 above), but perfect is the enemy of good in this case. Our legislators will take years to make relevant changes to HIPAA, so it’s important to stand up a national network for prior authorization with the existing caveats and barriers.

No matter what happens, the national technology ecosystem in healthcare continues to evolve, mature and become more complex as we move into 2022 and beyond. In this complex and multifaceted exchange stands opportunity by the boatload for vendors: the opportunity to solve payer problems, the opportunity to become the focal point of net new regulatorily required networks, and the opportunity to help providers and patients access new data. At a minimum, new regulation creates small new growth, but as we’ve seen with Surescripts and other example, there are empires to be built when the stars align. Some businesses will grow and thrive by capitalizing on these opportunities, whereas others will stagnate as these technologies act as headwinds to their corporate strategy.

Which will yours be?

Big thanks to my editors, Dhruv Vasishtha (the king of value based virtual specialty care and event notification) and Garrett Rhodes (the Payer Integration Guy™). Both very smart dudes who are worth a connect/follow/sly DM if you like good content and/or conversations.

Editorial note: Apologies for this piece on 2022 coming out (*checks notes*) over a week into 2022. Time is a flat circle when you’re home for the holidays and it turns out productivity drops immensely.