Epic v. Particle 2: The Problem of Secondary Use

How the white and black of data privacy quickly seem grey

Author’s note: This article is a follow-up and deep dive layering on the foundation of Epic v. Particle. Readers are best served to read that piece first for core concepts and understanding of the dispute, associated actors, and important actions.

Necessary legal bits: This is not intended to serve as legal advice nor should it substitute for legal counsel. This is not exhaustive and is meant to be informative, educational, and impartial.

Kat McDavitt of Innsena posted on Monday about the Particle v. Epic dispute:

This was ostensibly in response to Sunday’s press release by Particle, in which they stated:

While we have followed all guidelines and consistently acted in good faith, there is, in fact, no standard reference to assess the definition of Treatment nor the application of the definition of treatment as it pertains to data requests. These definitions have become more difficult to delineate as care becomes more complicated with providers, payers, and payviders all merging in various large healthcare conglomerates. The growth of value based care continues to blur that line as well. We welcome this discussion. It’s in fact a discussion we have been actively having with Carequality for months.

Ad hominem attacks aside for a second, Kat’s post is worth mentioning for two reasons:

The fact sheets from HHS she mentions are great resources on the basics of Permitted Purposes in HIPAA, including some fun early 2000s aesthetic diagrams.

She prompts some deeper thinking: Given that HIPAA has defined the Purposes of Use, how could there possibly be a grey area?

My take is that, at face value, purposes of use are well-defined by HIPAA and supporting materials such as those fact sheets or this HHS presentation. A single action in a vacuum can be assessed as Treatment, Operations, or any of the other purposes of use. Ignoring prior legislation, regulation, executive branch guidance, and jurisprudence comes at the same risk as ignoring any federal or state government edict. A small subset of bad actors on these networks, through possible malice but mostly ignorance, choose that path. As Patrick McKenzie writes in his excellent essay on value exchange in banking, the optimal amount of fraud is non-zero, as the only way to prevent fraud is not to exchange at all. We can only choose policies that balance the tradeoff of lowering fraud against legitimate users' ease of transacting.

The bulk of questionable entries and the crux of the confusion exists not in the white or black but in something referenced briefly but not fully addressed in the last article - secondary use.

Businesses are rarely homogeneous. They are a series of heterogeneous functions and roles working in concert towards a shared goal (or at least good ones are). At larger scales and sizes, you often have vastly different products and services under a single banner, a portfolio of tools with various users and use cases.

Take, for example, a hospital such as Mayo Clinic. This organization may have an upcoming appointment for a patient. To treat that patient, they pull from all the organizations across Carequality and Commonwell, using the data to prepare for the visit and identify prior medications and conditions. After the visit is done, they fulfill reciprocity by returning the summary of that visit to any organizations that query them.

The black-and-white seems clear here but quickly gets murkier. Having reviewed and reconciled the data with the patient during the provider’s visit, the medications, allergies, and other data are now shown in the patient portal. Furthermore, the hospital later launched a campaign to help their patients with diabetes and market a new program to them.

We highlighted the purposes of use in the last article and their importance when querying for data on the nationwide networks. That primary purpose of use is paramount because Treatment is the only one participants must respond to today. However, the action of showing the data to the patient starts to resemble Patient Request/Individual Access Services. Likewise, the action of marketing to the patient is not one of Treatment but of Operations.

These are examples of secondary use - the practice of using data initially collected for one purpose (such as clinical care) for another, unrelated purpose (such as research, policy-making, or administrative needs). Those are not the only secondary uses - data may be used to educate healthcare professionals, to help hospital administrators make logistics and planning decisions, and for doctors involved in research to study disease patterns in more detail. Those are actions that a healthcare organization logically does during their business.

Secondary use is complex and quite thorny to untangle, but it’s not a new problem at all - far more intelligent people than I have been thinking about it since the dawn of HIPAA, as this 2007 paper shows:

Secondary uses of health data can enhance individuals’ health care experiences, expand knowledge about diseases and treatments, strengthen understanding of health care systems’ effectiveness and efficiency, support public health and security goals, and aid businesses in meeting customers’ needs. Yet, access to and use of health data pose complex ethical, political, technical, and economic challenges. For example, to meet public health, emergency preparedness, and homeland security imperatives the federal government has initiated real-time collection of data from emergency rooms and other sources—without public dialogue, based on authority from existing public health law. Further, there are reports of the buying and selling of non-anonymized patient and provider data by the medical industry—carried out without explicit consent from patients or physicians. Such activities include pressuring or coercing patients to consent to data disclosure for use not covered by regulation, and abuses of commercially available, identifiable patient information. It is far from the only material on the subject, and it’s not unique to healthcare.

In a world where the discussion of secondary use is no longer about the data I collect within my enterprise but data collected by other enterprises, the discussion feels different than the angle many of these papers pursue. Health information exchange at scale turns secondary use from an organizational compliance decision into a network architecture discussion.

I was surprised to see how the aforementioned 2007 presentation by the HHS briefly but aptly predicted our quandary (where NHIN is the National Health Information Network, which has evolved into eHealth Exchange):

Does NHIN provide new pathways or sharing environment that causes us to reassess today’s balances? If so, what is the new functionality and

which uses/disclosures are most affected?Notably, Carequality does have some rules about secondary use once data has been used for its primary purpose:

This description is very non-prescriptive - secondary use is allowed for anything, so long as you’re following applicable laws like HIPAA.

Put simply, the ubiquitous exchange of data between enterprises via nationwide networks spotlights the issue of secondary use of health data, possibly exposing limitations and ambiguities in existing regulations and guidelines that were written in an era of more siloed data. So, let’s examine that newfound ambiguity and consider how to solve it.

Traditional healthcare organizations and secondary use

If we were to graph out all the work that the Mayo Clinic does, it may look something like this:

My informal taxonomy of secondary use tends to think about internal and external uses:

Internal: Using retrieved data for other purposes within the organization, like population studies or surfacing in a patient portal

External: Sharing retrieved data with other parties, such as payers, pharmaceutical organizations, or life insurance.

A large portion of Mayo’s use of data is internal. Their primary business is providing care, with other purposes supporting that business. However, as Particle notes in their post, some providers have expanded into a wider variety of services:

These definitions have become more difficult to delineate as care becomes more complicated with providers, payers, and payviders all merging in various large healthcare conglomerates

To their point, payvider groups like Kaiser Permanente might have different breakdowns if we were to map purpose of use across their business:

Regardless, even as they add diverse business lines to their operations, most of these traditional healthcare organizations still have a primary goal of Treatment.

Digital health and secondary use

As Carequality and Commonwell were founded, most organizations joining fit this model. However, with the advent of digital health’s expansion in the pandemic era and the new on-ramps to the health information networks, startups seeking to solve problems for organizations that lacked digital access to health data began to join the health information networks.

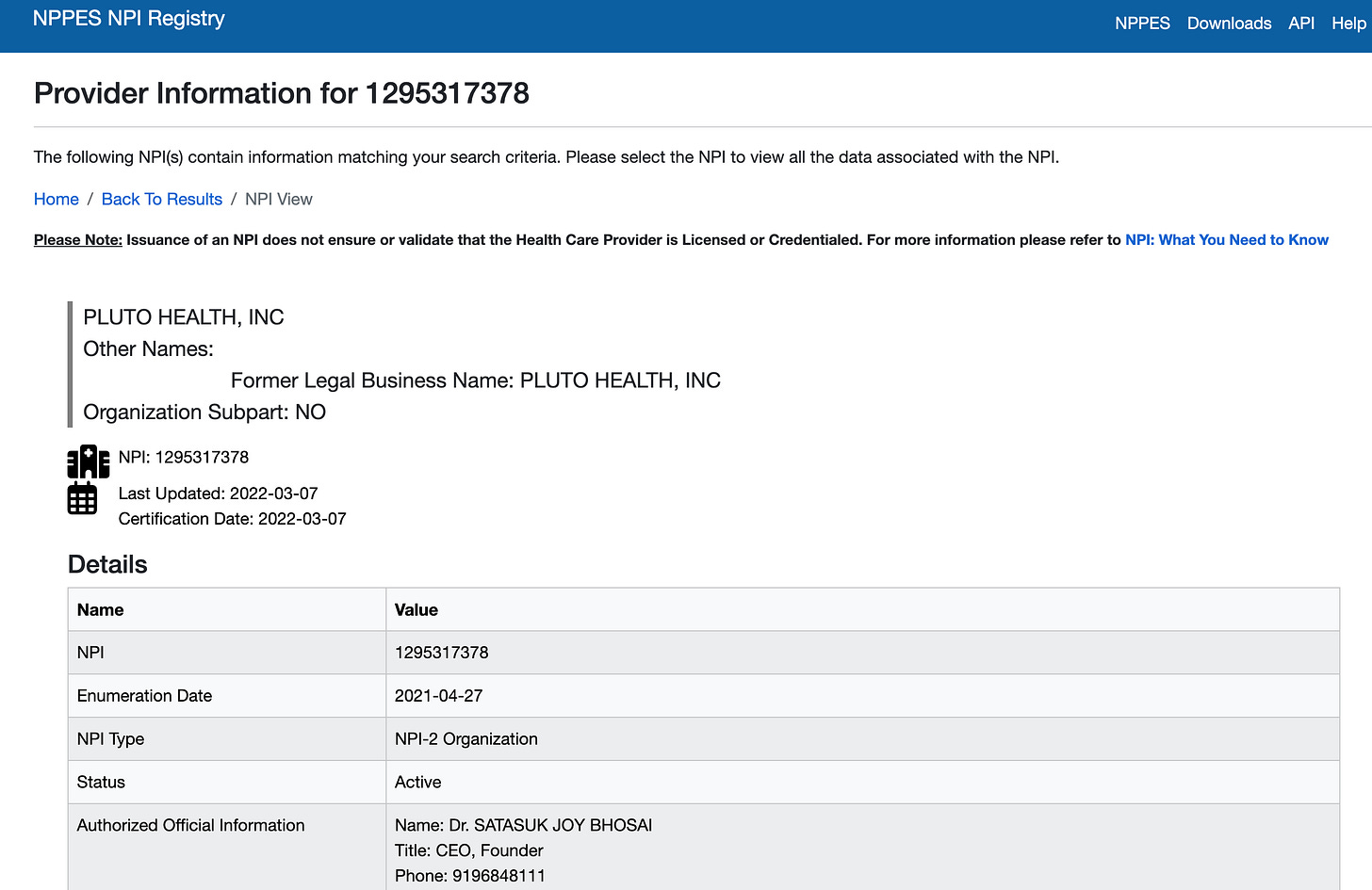

After publishing Particle v. Epic, several individuals sent various other companies they had questions about. In particular, many individuals mentioned Pluto Health. Their marketing website appears to message to patients and clinicians:

They also contain specific language on their website about not sharing or selling data:

At the same time, their customers are primarily not traditional practices, and their messaging suggests a flywheel of sharing:

By all available information, this organization (and many others in the grey zone) could be in adherence to network rules. They are registered in NPPES as a provider organization with an NPI:

They also employ providers, as their founder is a doctor, and they have a few nurses on staff:

If those nurses provide Treatment, even briefly, and contribute back clinical data to satisfy reciprocity, then by all measures, they may be compliant.

Interestingly, it’s apparent that they have had a tough time staying on any one implementer. Looking at the Carequality directory:

Hypothetically, it could be Pluto continues to try new vendors to optimize, but, more likely, on-ramps can’t decide what to do with companies in these grey areas.

Without more transparency on the clinical and business model, we can only guess, but if we were to profile Pluto Health like we did Mayo, we might find something like this:

They may be the first of this model (or the ones that most people chose to highlight), but given the advantages of using extremely light Treatment to pull data, they are not the last. PicnicHealth, a startup that has similar goals of helping patients share data with pharmaceutical and clinical trials companies, recently launched a Pluto copycat, PicnicCare (via the Particle on-ramp):

The Spectrum of Secondary Use

If we plot the pie graphs we saw for Mayo, Kaiser and Pluto Health and apply that same hypothetical analysis to all groups that use the networks, we unsurprisingly find other breakdowns that form a sliding scale with all shades ranging from “Treatment is the main focus of their business” to “They provide almost no Treatment”:

All these groups have some component that, in a HIPAA-compliant way, sells or shares patient data to pharmaceutical companies (either in de-identified fashion or with explicit consent) - it’s just a question of how much of that is their main focus and how much of the data they share comes from secondary use rather than their own care. The middle fundamentally is the grey area - everything until “no Treatment provided” is seemingly allowed under current rules, even if it conflicts with common sense.

Complicating things further:

An organization’s primary use at any given point in time may be distinct from its overall business objectives.

This appears to be Integritort's claim—that it is an organization mostly geared to sharing data with law firms but sees patients and provides Treatment to kick off that process.

An organization may have products or services that are clearly Treatment, but have other business units that are clearly not.

One great example is Clover Assistant. This tool is provider-facing, used actively in Treatment, and produces unique clinical data to contribute back to the networks.

However, Clover Health also has a separate Medicare Advantage line of business.

“On Behalf Of” applications (explained in the first article) complicate secondary use quite a bit.

If an application is truly a view-only application in the context of Treatment, but then data is used actively via secondary use for Operations, Payment, or other use cases, it seems very questionable that its primary purpose of use is Treatment at all.

This was the issue with MDPortals and Reveleer, based on Epic’s Issue Notification.

The questions raised as we think about moving the goalposts for secondary use lack clear answers:

Is it not okay at all? Should we ban secondary use, as the CFPB is proposing for fintech?

Asking entities exchanging data to segment or wall off data based on how they got it - i.e., use it for treatment and no other purpose - makes no sense.

We don't do that today when data is ingested through mechanisms other than network exchange, and it doesn't necessarily make sense to do it with network exchange, either.

If retrieved data cannot be incorporated into the general chart, many existing workflows for healthcare organizations would be handicapped.

Is it fully allowable so long as they have a provider listed as on staff?

If so, we are essentially sanctioning a Treatment workaround to HIPAA and should do so explicitly to remove the grey area.

Is there some other line in the middle we should draw? How do we measure that discretely?

Rules like “If 50% or more of your revenue comes directly from provision of care,” push organizations towards that new lower bound.

There is no clear solution for today’s problematic secondary use behaviors by simply changing the line in the sand of what is considered right or wrong.

Solving Secondary Use

Just like my main take for the Particle and Epic situation was that the tactical actions and who’s right or wrong really aren’t that important, I similarly think here that debating the line in the sand is an exercise in futility. There’s no easy button here, so long as Treatment is the only available purpose of use, and I don’t believe Pluto or others are necessarily doing anything wrong if evaluated by current network rules. The current system of Treatment-only forces groups down the path given no other viable routes to achieve what they need.

In the short term, more transparency across the networks on secondary use could help the situation. Carequality or Commonwell could require organizations to list their known secondary uses in the directory or include them in the queries sent to responding organizations. With more transparency on secondary use, patients could be more aware of how their data is used (especially if the auditing and observability suggestions I mentioned were implemented).

On-ramps exist to accelerate the adoption of Carequality and other health information networks through modalities that are better than IHE standards - APIs, simple UIs, automatic EHR integration - and provide value-added services such as de-duplication and augmentation. Given that mission and their lack of direct patient contact/consent, on-ramps should be restricted from secondary use aside from product development.

Similarly, On Behalf Of organizations are permitted to forego reciprocity in order to allow novel adoption of view-only Treatment modalities to promote innovation (such as an application tailored to surfacing the data optimized for oncologists or a more episodic view for obstetricians). While they can be valuable, the reality of OBO applications is that they should be an incredibly small fraction of the network - the bulk of applications actually do something, have user workflows, and produce some data that is useful for the overall longitudinal patient picture, even if small. A large number of OBO applications is not only not accurate to the reality of healthcare workflows, but also bad for network health - networks thrive when all participants contribute. It is and should be held to a much higher bar and disincentivized through strict approval process friction, high levels of scrutiny, and other levers. To the point of this article, one such lever is that can and should be added - secondary use of retrieved data should be limited to product development only.

More practically, because the grey area exists and infuses doubt and a lack of trust into the system, I’d strongly encourage organizations that could be perceived as questionable to proactively share their story and explain their participation in the networks. As mentioned in the last article, transparency engenders trust, while the opaqueness of hiding in the shadows, at best, leaves the narrative to the imagination and, at worst, confirms malfeasance. Types of groups that currently exist in the Carequality directory that would benefit from transparency:

Care delivery organizations where their primary revenue comes from the sale or sharing of data with non-HIPAA entities

Care delivery organizations whose product may be mistaken for a Personal Health Record or patient community platform

Clinical trial matching platforms and services

Health plans/insurance carriers

Medical device companies

Pharmaceutical companies

Law firms

Business associate software vendors that do not directly employ providers and do not list their partner organizations in the Carequality directory

Public statements are not the only form of transparency that may help. While secondary use cannot be encoded into the directory, digital health organizations can use existing hierarchical structure today to show their involvement and better emphasize their provider relationships.

For business associates, for example, structuring your entries to show your product and the covered entities you represent best conveys your Treatment purpose of use:

Likewise, for payers, medical device companies, and other entities that have multiple lines of business, highlight your software solution and associated providers best convey the exact product that is using the data:

The real panacea, though, will sound like a broken record - the primary way to stamp out the grey area is to reduce the demand for it by ensuring other purposes of use are equally available options. If patients could easily and safely share their data with groups like Walmart, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson, there would not be the same need to use Treatment in this way. If we do not accomplish this, then the path of secondary use becomes cemented as the method of access for non-HIPAA entities. The spectrum will continue to be flooded by organizations that are Treatment in name only, employing a single provider, contributing no meaningful data, and weakening trust until it breaks.

This is not to say that there won’t still be bad actors in a world with Individual Access and other Purposes of Use properly defined. The other use cases are likely to have additional conditions that have to be met that make them harder, such as Individual Access requiring strict identity proofing. As a result, we may still see people who aren't actually treating patients or are doing handwavy minimal care still trying to ride that Treatment train. Their choice to circumvent the rules will be not one of necessity due to no other options, but a calculated decision that we can better police and punish. That world certainly seems preferable to the debate in a constant cloud of grey that we are in today.

As always, a big thank you to Garrett Rhodes, Deven McGraw, and other editors who reviewed this

Thanks! The two articles on data flow really resonated with the challenges I face as an API product manager in fintech and healthcare. A key question is how providers and owners can maintain control of shared data and prevent unauthorized resharing, primary or secondary. Right now, this process is often a black box for users who give consent. I believe our industry needs to work towards greater transparency in data sharing practices.

If Particle has willing connected participants to Carequality who now seem to have questionable purposes, it seems that other on ramps have also done the same. Its a question that begs answering from all of the Implementors.