“Who are you?”

The digital systems sing.

“Who, who, who, who?”

This era we’re living through is eerily reminiscent of the legendary song by the Who - an endlessly recurring refrain. Instead of Roger Daltrey’s sultry tones, though, it’s a choir of electronic accounts, registration screens, passwords, two-factor emails, and QR codes.

“Who are you?”

This relentless torrent only increases year-over-year as we surround ourselves with more automation, trending inexorably towards the virtual future, the pace unexpectedly accelerated by the forces of the pandemic.

“Who, who, who, who?”

The question they all ask is a simple one. Understanding and proving a person’s identity is fundamental to almost nearly anything we wish to do, whether in healthcare or elsewhere. Very few jobs to be done can exist without that foundation. We need identity to establish trust. We need trust to understand that we share values, mores, rules, and laws. We need that understanding to prevent fraud, abuse, and outright betrayal. In an identity-less society, the contracts we’ve built as a society begin to fragment and fail - at least as we’ve structured them today.

This article is an exploration of identity (especially in the digital context). It will highlight the status quo in healthcare and the cumbersome workflows of traditional health systems. We’ll even discuss why I signed up for every Epic patient portal in the country (and it’s not just because I’m a sicko for pain).

🚨 Red Alert 🚨

Before moving any further, my humble request / demand is that you visit Flexpa’s home page. My ability to write is predicated on the existence of this company, which coincidentally deals deeply with identity (via the patients we connect). Moreover, we provide the easiest way for applications to connect to identified claims data, which is pretty damn sweet.

We’ve given it a facelift recently, so even if you don’t like claims data (gasp), we’d still love your feedback.

Identity is not solely a problem of the digital era. The history of identity is long and storied. We scribble our names on checks and papers to prove our identity. We imprint cards with our pictures and carry them all day in our pockets to verify our identity. We have entire businesses dedicated to aggregating key life events solely to ensure we are good and trustworthy.

These processes are and were never enough. No one checks a signature. Passports and licenses can be forged. Credit bureaus amass information, but often at a rate far too lethargic to be accurate. But they have always served as friction: adding hoops to jump through, obstacles to be overcome, and just enough pain and risk to dissuade the casual amateur from breaking our systems. Most importantly, in a pre-electronic world, the act of physical presence could supplement these tools, bringing identity accuracy to semi-acceptable levels.

The nature of our virtual world now breaks all assumptions, though. Digital consumerism demands less friction, not more. We want algorithmic recommendations. We want one-click purchases. We want instant delivery and gratification. The unintentional (yet somewhat effective) friction inherent to physical, analog tools acted as a deterrent to abuse and fraud but now stands squarely in the way of the digital progress’ forward march.

Core Definitions

Before discussing anything healthcare specific, how about a whirlwind tour through some foundational identity nomenclature? I hope I’m not running roughshod over the traditional teachings of identity wonks - I intend for these rough explanations to give us some baseline sub-denominations to play with.

When considering how users interact with software, we can think about a few primary concepts related to identification:

Registration: This is the initiation process. A user creates an account with a service or platform and provides certain information, like a username, password, and perhaps additional details like an email address or phone number. This is an optional step - not all resources need (or even want) you to identify in order to access resources or functionality, in which case registration is not necessary.

Authentication: This is the process of verifying that an individual is who they claim to be when they return to the service or platform. Typically, this involves the user providing their username and password, which the system checks against the stored data from registration. If the entered data matches the stored data, the user is authenticated. Again, this is optional.

Identity Verification: The process of confirming that a digital identity corresponds to a real, physical person, through proof of physical identity. While authentication confirms that the person entering the credentials is the same person who registered, it doesn't confirm that the identity claimed at registration corresponds to a real person.

Authorization: Authorization is the process of determining what permissions an authenticated user has within a system – in other words, what they are allowed to do. Once a user's identity is confirmed through authentication, the system checks its records to see what level of access the user should be granted.

Access: Access refers to the act of using resources, be they data, functions, or services, within a system. Access is typically facilitated by processes such as registration and authentication. Once a user is authenticated, they are granted access to the system's resources. The level or extent of this access can vary greatly depending on the user's authorization level.

Now, let's bring these concepts to life with a relatable scenario. Imagine, if you will, a night out at a popular club, 'Club Fever.'

Your friend, who rented the club, has created a list of invitees and handed it to the bouncer (Registration). When you arrive, the bouncer checks if your name is on that list (Authentication), then confirms the details on your government ID match your appearance (Identity Verification). Once these checks are done and feeling a bit thirsty, you head to the bar. The bartender, before pouring your drink, checks your ID to ensure you're of legal drinking age (Authorization). You enjoy a cold beverage of your choosing (Access).

Identity Workflows

In the modern consumer experience, we see a few common ways identity is exposed in digital workflows, each requiring increasingly more complex levels of identity controls to mitigate the risk of abuse.

Actions without identification (“We don’t care who you are”): This occurs when information is not protected. In this case, the actions available to users in a system, application, or website do not have an intrinsic risk of abuse or fraud, so access is not gated by registration or authentication. Generally, this consists of read operations of non-sensitive, public data, like opening the Delta app to look at available flights, reading articles on Wikipedia, or perusing Twitter. But in some cases, this may include innocuous writes, like anonymous commenting.

Actions requiring account creation (“Tell us who you are”): Not all actions can be open. Access control is needed in order to move beyond “what everyone can do” to “what you as a specifically privileged user can do,” so basic registration and authentication become necessary. As users start to participate - creating and altering things in websites, apps, or any ecosystem - it becomes important to tie the amorphous, anonymous blob of level 1 to an account. This could be for tracking their actions over time, rewarding good behavior, and punishing bad behavior. Risks associated with bad behavior at this level remain low enough that keeping things lightweight and low friction is desirable, but still - as you allow for deeper interactions, you need to prevent things like fraudulent payments, racist comments, and inappropriate content.

Actions requiring identity verification (“Prove who you are”): Sometimes, you really need to trust someone. In these cases, getting them to demonstrate who they are beyond just self-contained enterprise account credentials, tethering to their identity in the real world, is important. This process could involve answering a bunch of random questions about their financial and social history. Or it could require a picture of a trusted identity document along with some bank statements. It could be biometric data. Regardless, this moves the needle from “yeah, they filled in some information and provided an email for us to spam” to “we’re probably about 92% confident they are who they say they are, and we’re willing to go with that.”

Actions requiring in-person proof of identity (“Show us who you are”): Sometimes the data is too private, the zeroes after the dollar sign are too high, or people are just too old-fashioned. In those cases, we resort to the nuclear option - in-person meetings as a proxy for identity. It’s a frankly outdated concept in this digital era, but we still haven’t found the path to kicking this bad habit - see the ongoing existence of the notary occupation. Showing up in person at the bank or at a doctor’s office leads to more trust that I am who I say I am, which allows those actors to do inherently risky things for me, such as giving me that big loan to buy a house or prescribe me controlled medicines (hopefully not at the same time).

As we climb up these increasing levels of security, additional verification methods typically arise, each corresponding to one or more of three authentication factors:

things you know – like a password or security question

things you have – government or school-issued ID are fairly common here, but bank statements or anything mailed to you

things you are – biometrics

Actions without identification obviously require none of these factors. Open resources need no proof of identity. As we move up the ladder, though, actions requiring account creation normally ask for one factor of identity, actions requiring proof of identity prompt for at least two, and actions requiring in-person proof of identity necessitate all three.

Identity and Trust

Okay, that was a lot of learning, so let’s pause for a second - why should we care about all this?

Trust underpins all interactions, virtual or otherwise. Identity is key to trust - if I don’t know who you are, it becomes very difficult to trust you! So simpler, easier identity verification logically (but not always clearly) has huge benefits to all interactions. If I can identify you quickly, we can get to any service’s point of value more quickly - making a payment, interacting on a social platform, or receiving care from a provider. It is in everyone’s best interest to encourage and adopt better systems of identity at the application, organization, local, and even national scale.

Identity is a spectrum balancing two nearly opposite forces that all products and organizations optimize for in some way - privacy and friction. Modern consumer experiences are all about friction reduction - minimizing the number of steps a user must take to see value:

However, to ad-lib Uncle Ben, with great friction comes great privacy. Most practices that promote privacy inherently rely on friction as a main mechanism to prevent fraud and abuse. If one were to pursue privacy and data security in the most aggressive, maximal way, the logical end state would simply be no sharing or interaction at all! If no one has access, no abuse can occur. As Patrick McKenzie writes in the truly excellent “The optimal amount of fraud is non-zero”:

All fraud is a) an abuse of trust causing b) monetary losses for the defrauded and c) monetary gain for the fraudster. You could zero fraud by never trusting anyone in any circumstance.

Yes, there are obvious repercussions to this strategy in terms of hindering and slowing business operations. Nevertheless, I’m sure it doesn’t sound that foreign to any group that has had to complete hospital security questionnaires. Competent organizations know they need to find a satisfactory privacy path to achieving their business outcomes because (again quoting McKenzie’s article):

The marginal return of permitting fraud against you is plausibly greater than zero, and therefore, you should welcome greater than zero fraud.

All organizations must establish trust in order to do business. The level of trust needed varies based on the potential value and risk of a relationship. Thus, the level of friction is a sliding scale:

The categories of identity control we mentioned before are simply slices along this spectrum, representing increasing friction to dissuade most (if not all) fraudsters and achieve the acceptable level of abuse for a business. If the value at risk in the event of fraudulent access is extremely high, such as a large loan, you bias strongly towards the right side of the scale, as the marginal return of a few new customers is heavily outweighed by a single bad actor. However, if the risk of abuse or fraud is low, as with browsing a website, reading blog articles, or following social media accounts, you can make your UX and design teams extremely happy by wholeheartedly pursuing an optimal consumer experience.

The cool thing about technology is that it changes the game, even though the players are the same. Selfies, liveness checks, document scans, and all the novel features coming onto the market simply work better than what we previously had. The sliding scale still exists and always will, but the pain of the friction drops, and the gap between the two poles of our scale is drastically reduced.

Regional Identity

Something fascinating and under-appreciated about this space is that even a topic as cardinal as identity varies drastically by geography. In America, a license or passport is considered a strong form of identification because:

The government is largely trusted as an institution

Photographic identification is ubiquitous and trusted

This is not a given elsewhere! For instance, governments may not be able to reliably issue identification. Identification may instead be digital in some geographies. Societal differences matter and trickle down to these very core ways we interact and the systems we build. For example, Kenya has been trying to introduce a new form of biometric identification, Huduma Namba, with the intent of consolidating various forms of ID into a single, comprehensive system. However, as recently as this week, the president of Kenya called that identity initiative “a complete fraud.”

One other unique, fundamentally American facet of identity is the surreal waltz we perform with credit bureaus in our current dance of domestic identity. These bureaucratic behemoths - Experian, TransUnion, Equifax - have morphed from bean counters of financial responsibility into quasi-authorities of identity validation. They accumulate minutiae from the breadcrumbs of our lives: loans applied for, credit card payments made, addresses lived at, vehicles owned, and your mother's maiden name, of course.

It's almost as if we've outsourced the memory bank of our existence to these corporate custodians, who clutch our data close to their ledger-filled chests, yet seem to spill it out with astonishing regularity (shout out Equifax). Instead of a societal judge peering over reading glasses, sternly asking, "Do you promise to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth?" we've got Experian squinting at us, asking, "Is your pet's name really Fluffy?" and "Did you live in Alaska, Ghana, Massachusetts or Oregon?"

This is (and I cannot emphasize this last part strongly enough) not normal. To fully trace this lineage is out of the scope of this article, but: vastly simplifying, America’s unique propensity for inventing novel financial instruments slowly turned a nation of savers (circa 1940) into the most aggressively debt-fueled, credit-hungry population of borrowers in the world (see “A Piece of the Action” to deep dive on that transformation). In order to back the credit needed for this appetite, organizations were created to monitor and assess the creditworthiness of borrowers. Although they started as local and regional non-profits, over time, they've transformed into the multinational behemoths we know today. Nowhere else, though, are they relied upon so centrally.

So, the American reliance on credit bureaus for identity verification is a byproduct of the country's financial evolution, and as with any system, it has its strengths and weaknesses. While these institutions serve a necessary function in the current financial system, their practices, influence, and the amount of data they hold raise further concerns about their role in payments. The fact that we’ve yoked the even more foundational concept of identity (and, with it, healthcare) onto credit bureaus in the US is extremely questionable, especially given the flaws in their solutions.

Identity in Healthcare

When it specifically comes to healthcare and other privacy-conscious industries, it should be no shocker that the prevailing digital status quo for identity has maxed out on our spectrum with a default of “show us who you are”. For decades, data in health and finance have been protected by legal penalties, regulatory barriers, and the geographical capture characteristic of the pre-digital era. Open access or self-asserted access was antithetical to those pressures. As a patient, your ability to access data was entirely dependent on a physical encounter.

It’s not surprising per se that healthcare organizations are overwhelmingly risk-averse when it comes to identity and access - health data is protected by HIPAA in a way that few other industries parallel. As you might remember from a previous article, the HIPAA Security Rule is brutal in its penalties yet vague in its requirements, leaving a strong incentive and proclivity for healthcare organizations to play it as safe as possible. As a result, patient-facing tools from provider organizations rarely have the ease of onboarding we see in traditional tech companies.

Healthcare’s tidal wave of virtual first care is starting to crest, which will apply the same pressures toward frictionless onboarding that we’ve seen in consumer tech or fintech. But we’re not there yet, so the average patient is forced to carry a printed access code after a visit to even begin engaging with their health data electronically.

There are a few conventional onboarding paradigms used by traditional healthcare systems and provider organizations:

Access code - This is by far the most common onboarding technique for patient portals, where portal accounts can only be created with an access code provided in person (often on an after-visit summary) following a visit. This assures identity by virtue of the physical interaction, but it’s a massive barrier to adoption, especially as we’ve gotten deeper into the pandemic era and telehealth has grown. This high friction is sometimes desirable to health systems as many EHRs charge them per patient portal account ($1-2).

Phone call - Some organizations allow new patients to submit their demographic information to generate a new account online, and registration staff will check proper identity via phone call. Realistically, this method prevents identity fraud less by means of the questions they may ask and more by the frictionful barrier to entry that pushes fraudsters towards easier, quicker paths.

Knowledge-based answers - Until recently the “modern” identity approach for healthcare organizations, it kicks the registering user over to a credit bureau to answer a series of questions about their aggregated consumer information, such as prior addresses, pet names, or home or auto payments. This ostensibly assures identity by making the identifying user provide answers only they could know. In reality, it’s a clunky process that frequently errors even when providing the correct information.

The Epic MyChart Experiment

If you’ve done any work in any other industry (especially fintech and modern banking) or traveled to places like Estonia or India, you’ll know the aforementioned methods of US credit bureaus are far from the most cutting-edge. We’ll circle back on all the cool stuff that’s out there (Government ID scanning! Selfies! Liveness video checks! Digital identity!) both domestically and abroad in a future article. For now, in an effort to canvas the current sad state of affairs, I spent around a year signing up for every patient portal I could in America, which I dumbed down to mean signing up for every MyChart, because:

Epic has the most robust patient portal capabilities of any traditional EHR through MyChart. Given each hospital has control over its onboarding process in MyChart, we should expect some of its customers to have onboarding and identity experiences that employ the most modern available approaches.

There was a readily available list of Epic sites here to run through.

I learned the myriad and byzantine mazes that health systems erect for new patients to navigate. I studied the secret passcodes needed to answer credit bureaus’ knowledge-based identity verification systems. I encountered every form of error, fault, and flaw possible in the onboarding process, showing humanity’s endless proclivity towards accidental deviation from the norm.

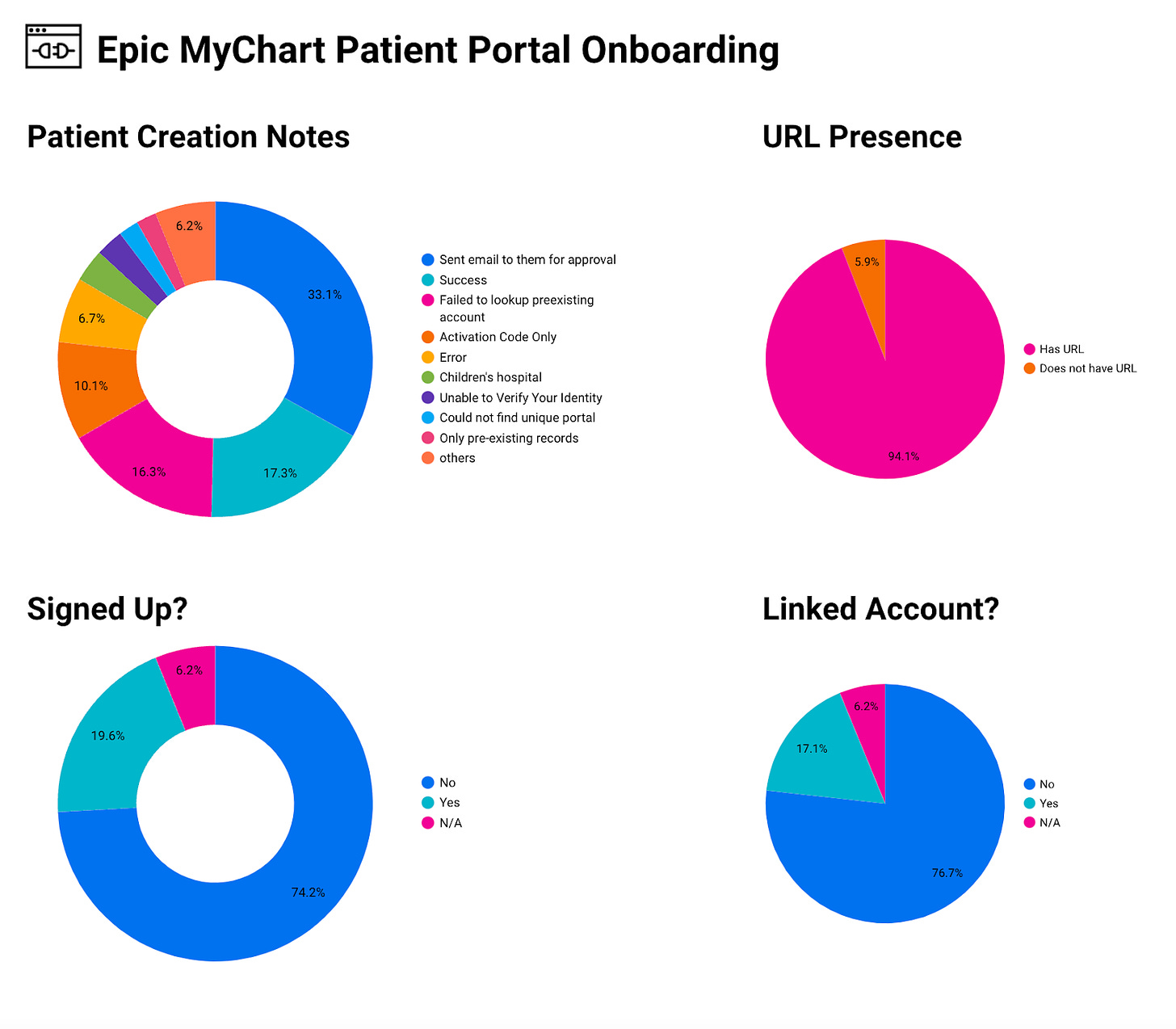

This was exceedingly manual work that I often did on plane rides. The data is a bit dated as I started in early 2021 and finished in February 2022, but is detailed in full here. It’s undoubtedly changed (there are definitely many new Epic health systems not included) and likely shifted slightly towards easier access. Given the tardiness on this particular piece already, let’s bias toward productivity rather than perfection and just ship it - I will enable comments so that any corrections or updates can be factored in.

Process

In the spreadsheet, you’ll see a few columns. Here’s what they mean:

Organization Name - Fairly simple. As I mentioned above, I sourced these from the FHIR endpoints list. If the organization has patient access FHIR APIs, they have a portal.

URL - A link to their patient portal for those of you that want to give a specific health system a try yourselves.

Signed up? - This column is a binary Yes/No to indicate whether I was able to register for the health system. Some are marked as N/A if I could not find a portal or if it was a children’s hospital (as I’ve been told repeatedly that I’m a grown adult and should act my age, I only tried to sign up for children’s health systems if I had been seen there).

Identity Vendor - in the event they allowed for registration and required identity verification, this column recorded which vendor they used

Patient Creation Notes - Notes about the registration process. For any organizations where I was able to sign up, it’s simply “Success”. Otherwise, this gives detail about the exact sort of failure I ran into, such as “Activation Code Only”, where new patient registration can only be completed with a registration code given after a visit, or “PDF Form to Access”, where I had to fill out and send a PDF.

Linked Account? - MyChart has a neat feature to allow me to unify my identity across MyChart instances, so that all my data shows up across portals. However, not all health systems have allowed this feature. Many have it misconfigured, so that the feature is available, but no organizations can be linked.

Linking Accounts Notes - If I was able to register and the unified identity management feature was enabled, this details whether I was able to successfully link my account across MyChart instances

Notes - Any additional things worth commenting on

Takeaways

The biggest takeaway from this exercise (which my loving wife fondly termed “a monumental waste of time, please stop signing up for MyCharts and watch the movie with me”) is that healthcare is DEFINITELY still stuck in the identity stone age. Even for Epic, the leader in mainstream healthcare technology, still less than 20% of customers are using the bare minimum of a modern identity flow. The process of patient account creation remains cemented in the era of in-person visits, reliant on phone calls and access codes.

Even the “innovative” approach of knowledge-based questions is incredibly flawed. The questions are only a minor obstacle to anyone with even rudimentary knowledge of a person’s demographics and a little social engineering, given only 3-4 answers per question. Beyond that, the failure rate was shockingly high - the service from Experian often malfunctioned and bombed out prematurely, requiring multiple attempts to navigate successfully. Additionally, for numerous health systems, it rejected correct answers, suggesting that source data backing the tool was out-of-date or just inaccurate.

Given the dismal state of the union here, it’s no surprise that portal activation rates at these institutions are terrible - one study found that 56.7% of patients had an inactive portal account (and, more damningly, 70.4% for non-English speakers). A second had rates sitting around 31%, with similar disappointing disparities across demographic groups. Another trumpeted their “success” in raising activation rates from 1% to 30%.

It is mind-boggling at first glance that healthcare organizations aren’t bending over backward to get more progressive here. Almost all metrics and measures show that increased portal usage benefits both patients and portals. For instance, one study found patient satisfaction with the availability of lab test results increased from 30% to over 97% for those who were using MyChart. On top of that, they also found that if less than 20% of responders to an outbound mailing activation campaign used MyChart once to pay a bill, that campaign would recoup the cost of the acquisition.

I feel like a crazy person having to say this because it should be blatantly obvious - patients should have a clear, low-friction path to verify their identity and activate that account. Activation codes need to be a thing of the past - healthcare organizations should be using the latest and greatest sign-up and activation flows, including maximizing multi-lingual and accessibility support to ensure all demographics can benefit. They should be pushing Epic and other EHR vendors on all patient sign-up and identity features to attract new customers, retain their existing patients with higher satisfaction, and reap the myriad ROI benefits of increased digital engagement. The EHR default for these advanced identity features should be “on”, given the clear value. And if the only real reason that health systems are not doing so is that $1-2 per patient…well, that seems like a good reason for some regulation to effect real change.

Conclusion

As the question of “Who are you?” reverberates in our minds, we come face to face with the profound transformation of identity in our digital era. The question of identity will not fade. It will continue to echo in our collective consciousness with increasing volume - shaping our interactions, governing our access, and playing a pivotal role in defining who we are in the virtual world. The archaic pen-on-paper signatures and those quaint, tiny photos on IDs were never foolproof, yet they got us this far. However, as the era of one-click purchases, on-demand services, and open access to consolidated data dawns, these analog methods are becoming the square pegs in the round holes of our digital existence.

Are we ready to tune our voices to the digital symphony and let the world know exactly who we are? The refrain continues: “Who, who, who, who?” It's a question not just for us as individuals but for the systems and structures that govern our identities. The song remains the same, but the answers? Those are evolving. Together, we're writing the new verses.

In the realm of healthcare, the revolution of identity is pressing on all fronts, compelled by the pressing need to balance swift, frictionless access with secure and private user interactions. Traditional methods of verification like access codes and knowledge-based answers have shown their cracks, underlining the urgency for a digital makeover. Despite the obstacles ahead, we should not retreat into the familiar comfort of the old ways. Instead, we must march towards the future, embracing innovation and progress while remaining cognizant of the potential pitfalls and perils.

So, as the drums of the digital age continue to pound, let's ensure we hit the right notes in shaping our digital identities. And let the world sing back, not with a question, but with a knowing: "That's who you are."

Kudos to the many editors and reviewers who contributed:

Colin Keeler, Business Development at Kiva

Bailey Davidson, LCSW

Jonathan Pira, Product at Teladoc

Luke Brown, Client Success at Alloy

Ben Lee, Founder at Quite a Few Claims

Bobby Guelich, CEO at Elion Health

Angela Liu, Design at Flexpa

If you liked this article, get excited - there’s more to come:

Over on the 🔥Flexpa Substack🔥, my colleague Angela Liu has published a deep dive into the identity and authorization flows of the payers we interact with daily. It’s an interesting parallel read in that payers don’t have a central system like the EHR to rely on for identity, so the set of problems and identity workflows takes a different shape.

In the next article in this series (this time over on the 🔥Flexpa Substack🔥), we'll dive more deeply into the future of identity - all the fun stuff like modern identity proofing, digital ID cards, biometric verification, blockchain-based identities, privacy-preserving identity systems, and decentralized identity solutions. We'll also look at what it would take for these technologies to be adopted domestically (especially in healthcare).

There's a really BIG friction - unique to healthcare - that was never referenced.

In our system of tiered (and constantly churning) coverage - the healthcare system isn't JUST focused on patient identity - they are critically focused on coverage identity - because that's where the bill goes.

And given all the variables to coverage (relo, change of employer, age, network, etc...) they are incentivized (for accuracy) to capture this information at the last possible moment - often on-site (hello Phreesia).

This becomes SO critical to healthcare providers that - even with a provider I see regularly (say dermatology) - I'm often asked to fill out the infamous "Patient Questionnaire" annually - and yup - all too often it's still clipboard and pen.

Interesting article!

We wrote an article about the crippled state of the Canadian healthcare system:

https://klarityvipwriters.substack.com/p/waiting-for-healthcare-in-canada

For Canadian readers, we have a Calgary-based company offering premium health insurance for an incredibly affordable price. Visit our page here https://www.klarityvip.com/ Don't wait to die waiting!