Amazon and the Presumption of Guilt

Why the One Medical deal does not mean big tech is stealing your data

When it comes to digital health, any news of big tech’s industry moves catalyzes tens (if not hundreds) of thousands of words from armchair pundits - a metaphoric Helen of Troy to launch a thousand Substack ships. So I’m not going to prognosticate too much here on the fundamentals of the deal. There’s more than enough literature on that topic coming from authors better suited to provide perspective there. That said, two high-level thoughts to level set:

But:

As you can see, I don’t think the One Medical deal matters all that much - it’s cool and exciting and makes a lot of sense for Amazon, but is ultimately similar to the rest of the consolidation that’s happening all over digital health.

The main reason I’m writing this brief article is to go full narrative violation and tell you: Amazon’s not here to steal your data. To do that, we need to sit down and have a talk about FUD.

The FUD Talk

Salt-N-Pepa said it best in their hit 1991 single:

Let's talk about FUD, baby

Let's talk about uncertainty

Let's talk about all tech’s bad things

That you imagine to be

If that’s not ringing a bell, perhaps the Merriam-Webster dictionary can lend a helping hand:

FUD noun

fear, uncertainty and doubt, usually evoked intentionally in order to put a competitor at a disadvantage.

"the FUD factor"

It’s the acronym of our era, whether in regards to unprecedented, generational, macro-scale crises that have arisen in the past three years, or just the general repetitive chanting of cryptobros reassuring themselves in the wake of economic downturn.

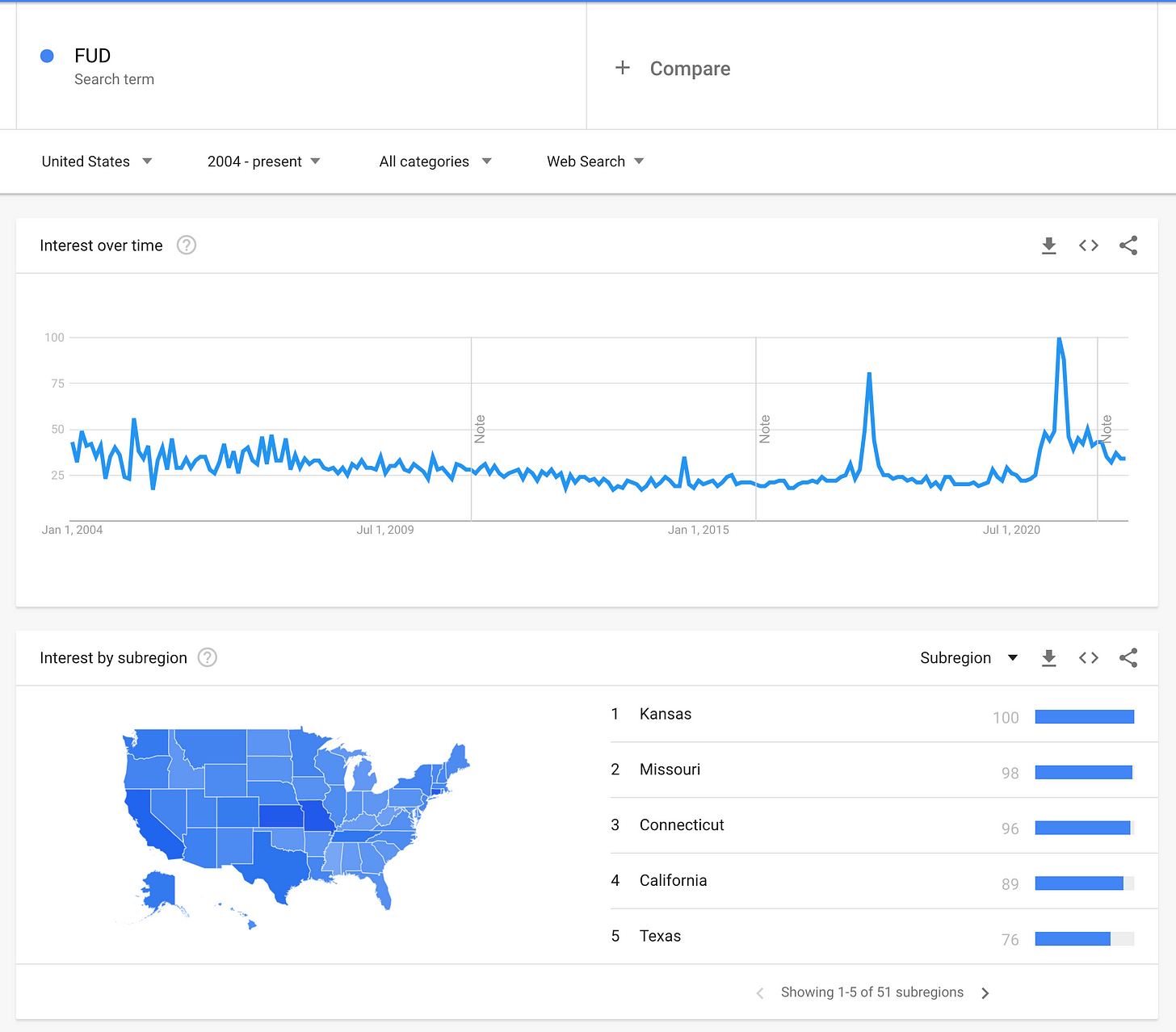

Heck, it’s apparent from the data alone:

So it shouldn’t be a surprise, I suppose, that this week’s Amazon acquisition news was met with unmitigated fear, uncertainty, and doubt:

The inherent distrust of big tech in healthcare is not necessarily new - it’s visible everywhere when operating in this industry. We saw it with Google and Project Nightingale at Ascension, and when they acquired Fitbit. There were calls to action with Oracle’s purchase of Cerner, with assertions that the tech giant might reidentify anonymous patient records to link to existing consumer data. Data privacy considerations have been on the rise, especially in the wake of the Supreme Court terminating the Due Process protections established under Roe v. Wade.

Despite all this, I’m flabbergasted.

Here are a few reasons why, in increasing priority:

Amazon’s organizational structure

Amazon is not one homogenous organization. It is not one shared database. It is highly siloed at a level beyond even competing tech giants. As this article states, this structure is deeply ingrained in company culture:

Its highly decentralized structure, with small, siloed teams, is the equivalent of "1,000 independent businesses, all marching in the same direction," says former Amazon senior manager Eric Heller, who now helps brands sell on the site.

With respect to healthcare, this is all the more true. Alexa Healthcare Skills, Amazoncare, AWS for Health, and Whole Foods run as entirely separate businesses, and today’s health efforts share little to no common lineage.

The common sentiment of expressed fears suggests that Amazon would about-face here; pool data and communicate in a large, cross-organizational way, unlike their functional present state. Accomplishing this would not be impossible, but you can’t turn the Titanic on a dime.

Data integration is hard

There’s an implicit assumption people seem to be running with that, once the deal goes through, One Medical health data will immediately, seamlessly, magically pipe into some greater Amazon ecosystem.

As I’ve written previously, though, merging tech stacks is inordinately complex work, so there would certainly be “fun” in store for anyone attempting to connect or combine Amazoncare’s athenahealth instance and the two homegrown EHRs of One Medical and Iora Health. As if that weren’t enough to manage, any further integration and operationalization of patient data with ancillary systems would be a massive undertaking - let alone the disparate systems of other business units (source: this was my job at Epic for 6 years)

The current regulatory environment

I don’t know about you, but the current political divide feels wider than the Grand Canyon. I can count on one hand (maybe two) the number of issues that have true bipartisan support.

This deal happens to sit right at the intersection of two bipartisan issues:

Data privacy - There’s never been more attention on consumer data rights. Literally two days ago we saw movement on one of the first major attempts to pass a national data privacy law that, remarkably, has leading experts in the field optimistic about its passage.

Healthcare antitrust - All government agencies and legislators seem to be coming around to the long-documented, broadly understood fact that massive healthcare consolidation over the past two decades stifled competition and adversely affected patients. The FTC is poised to take more aggressive action against healthcare mergers and acquisitions. The new head of the HHS, Xavier Becerra, has a storied history of antitrust action. Biden just issued an executive order that calls out healthcare markets.

Frankly, point 2 pretty clearly does not apply to Amazon’s acquisition by traditional antitrust standards - the merger is large, for sure, but does not drastically reduce consumer choice. The variety of national, virtual first care options has experienced a Cambrian explosion since the beginning of the pandemic, and traditional care centers have invested heavily into telehealth capabilities.

However, ground truth in antitrust law is changing, and precedent arguments supporting antitrust action may not necessarily be the rules applied to cases like these. The emotional and political aspects behind data privacy are strong enough that it’s not preposterous to imagine the FTC kicking off an investigation, given that lever is within easy reach. As noted in Ben Thompson’s Stratechery, legislators have already started to move beyond consumer welfare alone when considering antitrust action:

What is notable is what is not here: any reference to consumer welfare. Under current antitrust jurisprudence (which is not a constitutional right and can be changed via a law like this one) a company (1) first has to be a monopoly (with certain exceptions) and (2) can defend itself by showing customer benefit outweighs competitive harm. Both of these guardrails are removed by this legislation: a company is subject to regulation simply by being big enough, and it doesn’t matter how much benefit customers gain from their actions.

Point in case, some lawmakers are already eyeing the situation warily:

Amazon does not want to battle this in court. Thus, the easiest (and most likely) way for them to assuage the fear would be an explicit and public assertion of how they intend to use and share health data, as Google did in order to close the Fitbit acquisition.

Breaking the law is bad

As much as I like to throw on the figurative white wig and putz around at interpreting legislation and regulation, I am not a lawyer. So let a real one (Lucia Savage, one of healthcare 🐐s when it comes to policy) summarize the state of affairs:

Cool as it is to imagine all the good or evil Amazon’s various business units might do dipping into that sweet, sweet healthcare data, acting this way would blatantly violate existing federal and state statutes.

For this reason, it’s commonplace amongst large healthcare organizations with disparate business units to establish strong firewalls between said units. CVS, United, Apple, and many other players with magnitudes larger patient populations would be just as well served powering their retail business with your pharmacy and health data as Amazon’s retail business would - yet they don’t. For some reason, though, many presume that Amazon is more likely to do so, although they have significantly less to gain through that transgression. Amazon isn't the first company to be positioned to combine data in this way; we're just attacking them now because.... well... it's Amazon.

They can already access your data

Yes, you read that correctly. Amazoncare is a connection of a live Carequality Implementer (Particle Health), which means that it can already pull records from any and all EHRs live on that network (as well as the connected Commonwell and eHealth Exchange networks) for the purpose of use of treatment. These networks equate to roughly 75% of the US population and include all healthcare organizations that use the largest EHRs: Epic, Cerner, Meditech, athenahealth, Nextgen, PointClickCare, and more.

If Amazon was interested in brazenly aggregating patient data in violation of the law, they certainly don’t need the 767,000 members of One Medical. They can, today, already pull a much broader dataset with deeper insights (such as inpatient stays and specialty care) whenever they want. In truth, this is the area I’d pay more attention to, given we’ve seen an Amazon subsidiary get in trouble for flaunting a network’s rules through an unscrupulous intermediary once before.

Continue to extrapolate and it becomes apparent that if Amazon was obsessed with patient data acquisition and willing to break rules to get it, they natively have access to huge patient populations given that many health systems and digital health companies store their data on AWS. Again, if Amazon decided to shamelessly sidestep federal and state law and their own terms of service, they could do it on a much more massive scale than One Medical’s relatively small population.

The Bottom Line

When it comes to big tech, there’s a presumption of guilt - an inversion of “innocent until proven guilty”. I think this boils down to some visceral, basic human reaction to hate the winners and the dynasties, those that continue to triumph over and over again. We can’t stand the Cowboys, Patriots, or Yankees; part of me thinks it’s this instinctive response against continued, perceived-unbeatable success that causes us to lash out against Amazon and others like it. We project our worst fears of data abuse and misuse on the largest, strongest companies despite the good they might do.

Far more often, though, it’s the small entrants - hungry to survive, unable to invest in compliance, and living in the societal shadows of undistinguished obscurity - that are incentivized by ambition or misguided by innocent ignorance to turn off the accepted path. It’s just that their misdeeds are harder to spot without the magnifying glass that fame brings.

Our hysteria may be unwarranted for now, but our continued attention is not. The former serves as anxiety-inducing tabloid fodder, but the latter serves to hold these parties accountable for their actions, should they misstep. It’s less the outright illegal things we should fear, but the small iteratively creepy actions that we should worry about.

If FUD is wrong, then what is right? What does this news actually mean?

I’ll defer to a bunch of smart people to weigh in there. Jay and Nikhil, per usual, have excellent takes:

A few other nuggets I liked from a bunch of conversations about the topic this week also stood out, like Matt Ripkey from Redox:

Amazoncare is brand new. So while they can theoretically tap Carequality, they likely haven't qualified for treatment with as many patients as One Medical. So that's apples and oranges.

To me, they bought a great distribution into all the major cities ala Whole Foods, and at a good discount. That’s what makes more sense to me - this deal as a consumer distribution play than a data play to me. And today, the healthcare consumer experience sucks. Amazon gets people what they want at the cheapest prices right now. Why not believe the “obsess over the customer” thing can apply to “patients” too.

Similarly, an employee of the newly merged company:

It feels to me to be along the lines of that Shantanu Nundy tweet - OM needs more ways to onboard more patients into recurring primary care, lowering everyone’s total costs. Currently OM relies on subscription fees - it’s not unimaginable to think that the Amazon acquisition could give OM the financial flexibility to do away with the relatively large annual fee and bring on more patients.

Amazoncare was an attempt by Amazon to build a first best customer for its healthcare delivery operation by incubating it internally with employees. Progress was slow there, though, so this acquisition accelerates their ability to roll out that function. The likely outcome, then, is what Jay says: One Medical ends up like the Whole Food acquisition. It’ll be somewhat successful and have wide brand recognition, but will carry minimal integration into the greater Amazon ecosystem.

Whatever the outcome, one thing is clear: the One Medical acquisition is better than failing to purchase Twitter.

(Yes, I STILL know he's not CEO, but I'm riding this into the sunset)

Big thanks to the editing crew - Bailey Davidson for the first pass, Colin Keeler for meme upgrades, Tim Kessler for thoughtful additions and clarifications, Matt Ripkey for rapid-fire hot takes, and Jonathan Pira for treating this jungle of a piece with a judicious editorial machete.

Loved this paragraph: "Far more often, though, it’s the small entrants - hungry to survive, unable to invest in compliance, and living in the societal shadows of undistinguished obscurity - that are incentivized by ambition or misguided by innocent ignorance to turn off the accepted path. It’s just that their misdeeds are harder to spot without the magnifying glass that fame brings."

"I think this boils down to some visceral, basic human reaction to hate the winners and the dynasties, those that continue to triumph over and over again."

Not for me (and I've also written about similar hate for Epic - http://hc4.us/epichate ).

My disdain is the bubbly effervescence and breathless hyperventilating over theories that our mega tech companies will magically "disrupt" healthcare when the only real motivation is more revenue extraction.

Meanwhile the average cost of PPO coverage for an American family of 4 (through their employer) is now over $30,000 - per year - and about 150M American's get their health coverage through their employer.

No one industry segment is to blame, of course, but they're all complicit in revenue extraction - including big tech.