Regulation, the law, and other boring things made slightly more fun

A collab with Marissa Moore from OMERS to help you understand the impact of regulation on digital health this year

Wow, Q4 blew by. All has been quiet on the western front writing-wise since joining Flexpa, at least publicly. I’ve been slightly heads down getting shit done, but I’m hoping to change that this quarter, insofar as a number of topics I’ve had brewing are finally coming to fruition (identity! HIEs! another framework!). If you’d like that, then come check out Flexpa, peruse our robust developer documention, and use our self-service developer portal to get started pulling claims data, so that I can join fewer go-to-market calls and we can kill the enterprise sales motion once and for all 😊

In the meantime, you should read the article

and I put together that gives a broad, yet thorough overview of as many important regulatory items as you could shake a stick at:The rules, laws, and policy digital health needs to know to stay ahead this year

By

, Brendan KeelerLet's face it, healthcare regulations can be pretty confusing and outright overwhelming at times. With so many different rules, regulatory bodies, and constantly evolving guidance, it's hard to keep track of it all, especially given the hieroglyphic-level interpretation needed to parse even the shortest and simplest legal texts.

But here’s the thing: whether you work in a hospital, a health tech startup, or somewhere in between, staying updated on the latest policy and regulatory developments is essential for the success of your organization. They can directly impact the way you do business and deliver care, and failing to stay informed could, at best, leave you unprepared and, at worst, completely handicap your business. Being aware of the latest developments can help you anticipate and adapt to change faster than your competition, inform your strategic decision-making to perfectly time tailwinds, and protect your organization and ultimately patients from adverse consequences.

To aid those efforts, we compiled this high-level overview of some of the most pressing regulatory/policy concerns for health tech right now. This is far from comprehensive and occasionally opts for wit and brevity over fastidious precision - we recommend deep dives of the many articles and regulatory texts we’ve linked if any in particular spark joy or 😱. Despite (or perhaps as a result of) that fact, we hope you’ll find value and enjoyment in what we’ve summarized.

p.s. A special thank you to Libby Baney, Blake Madden, and Kelly Watson for your valuable contributions!

Interoperability

Interoperability is a twisted, tangled web, with laws, rules, and regulations by Congress, the ONC, and the CMS compounding, interfering, accelerating, and delaying the ideal end state all at the same time. It is still far from where we need to be in healthcare or as a nation. However, the main takeaway as we head into 2023 is that access is undoubtedly increasing: patients have broader capability to pull their data than ever before, exchange between providers for treatment is at an all-time high and accelerating, and applications for providers have a growing set of EHR API programs to connect to. For more relevant context and cute explanatory diagrams that act as a primer to the content below, read this summary.

Patient Access

This long and storied road of regulation aimed at increasing patient access starting with HIPAA has hit a new peak with the FHIR APIs required via the ONC Cures Act. This provision for a standardized patient API improves upon similar provisions in Meaningful Use 3 by providing exponentially more prescriptive guidance on the format (FHIR), version (R4), and protocols these EHRs must support.

When combined with the FHIR R4 patient access APIs that payers were required to expose in July 2021 as a result of CMS’ Interoperability and Patient Access Final Rule (similarly named but authoritatively unrelated to the Cures Act), a patient now can now have an expectation that they can access both their payer and provider data with just their username and password.

Or can they? Despite the continued progress on this front, numerous compounding challenges and gaps still exist:

Partial applicability: Not all payers are affected by the CMS regulation, leading some to only provide API-based access to Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and ACA populations, excluding the large number of patients on commercial plans. Similarly, nothing truly requires all providers to use certified EHRs, just a desire for slightly higher rates of CMS reimbursement

Non-compliance: Straightforward and brazen lack of adherence to regulation is still a large problem. This is pronounced on the payer side, where enforcement mechanisms by the CMS have been handwavy compared to the certified EHR program and associated CMS reimbursements. Over 40% of state Medicaid agencies have no implemented and planned solution.

Registration mazes: Impossible or lengthy application registration processes on EHR vendor or payer developer portals handicap connectivity. Turnaround times can drag on for weeks or months, with some affected parties simply having no discernible registration process in their portal at all.

Patient identity provisioning: Health systems are not required to issue a username and password to all patients (and for many, have EHRs with patient portals that charge per patient account, providing a strong disincentive to issue en masse)

Data set divergence: Despite relatively strong data set standards on the provider side, payers have divergent implementations in terms of data sets exposed, such as Epic hosted payviders not providing coverage details or select payers only exposing clinical and not claims data.

Data formatting: The data provided by these APIs is decidedly varied, with myriad differences in the fields exposed in each clinical resource by providers.

While no pending required regulation is directly aimed at patient access, many proposed or in-progress rules do have sub-regulation that expands existing connectivity. For instance, although CMS-0057-P, the CMS Advancing Interoperability and Improving Prior Authorization Processes Proposed Rule deals primarily with creating new electronic prior authorization processes, it also has some nice expansions to patient access by requiring prior authorization data to be included in existing flows. Likewise, the No Surprises Act (see section below) and its companion CMS-9900-NC, a Request for Information on Advanced Explanation of Benefits and Good Faith Estimate for Covered Individuals, is on paper about further nailing down price transparency. But by providing estimates of expected costs for upcoming visits or procedures via advanced explanation of benefits, the existing patient access APIs are strengthened. This should further empower a new class of applications and organizations to advise, advocate, and assist patients in their choices of care and plan navigation (assuming they make it through the hoops of regulatory revision and approval unscathed).

Trusted Exchange

Segueing a bit from the biggest unknown factoring into patient access, however, originally had little to do with patient access at all:

(Sec. 4003) The ONC must: (1) convene stakeholders to develop or support a framework and agreement for the secure exchange of health information between networks, (2) provide for testing of the framework and agreement, and (3) publish a list of networks that adopt the agreement.

These simple words in the 21st Century Cures Act in 2016 have ballooned into the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). Intended to establish a floor for interoperability across the country with governance and infrastructure to securely share basic clinical information with each other, it today strongly resembles another existing trust exchange framework, Carequality, in terms of legacy content and exchange standards. After leaving some scope on the cutting room floor, such as carved out requirements for payment and operations use cases and punting the use of FHIR to a future date, the main advance over its predecessor is the ability for patients to use such a frictionless nationwide network to pull their clinical data without need for provider-specific credentials.

The potential impact of this endeavor cannot be overstated. If fully adopted, it would enable patients that have gone through strong identity checking (as is popular in many fintech apps today with selfies and such) to aggregate their data. As a corollary, any organization or application a patient might authorize and choose to share their data with could much more easily access such data. Thus, the fates of many existing on-ramps to health information exchanges hang in the balance here, desperately hoping that TEFCA arrives and expands their TAM to profitability as life insurers, payers, and life sciences hungry for data look to take advantage of this new route.

Progress was made in 2022, with nine organizations signing on to attempt to be the first Qualified Health Information Networks (QHINs), a hurdle that was not sure to be cleared when we started last year. Moreover, the fact that major EHRs like Epic and Nextgen and health information exchanges like Commonwell, eHealth Exchange, and Health Gorilla chose to participate is promising.

However, the biggest barrier is that TEFCA is inherently voluntary - Cures neither provided the ONC or any other regulatory body with the authority to force all providers to join nor created a clean mechanism to force. The other major factor in play is that patient access is inherently unidirectional in nature, whereas the pre-existing dominant reason for exchange (treatment) had a principle of reciprocity, where each new participant would be contributing back net new care data. Reciprocity was a powerful incentive to participate: the value of the network grew with each new participant, as the picture of the patient’s care became fuller and fuller. This is lacking in the TEFCA world, insofar that some participants continue to add to the picture, but many will act simply as an operational drain, providing no value back to providers. As a result of the voluntary nature and generally unidirectional nature of patient access in TEFCA, there’s limited upside for those providers already operational in other networks to make the jump.

Some regulatory juice is perhaps waiting in the wings, however, to help inch things forward. The CMS added a new provision to the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program as an optional alternative to fulfill the Health Information Exchange (HIE) Objective option, the Enabling Exchange under the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) measure (requiring a yes/no response). Similarly, in the prior authorization proposed rule, the CMS solicits ideas for how to unify TEFCA with the existing Patient Access APIs and proposed Provider Access APIs in the future (which seems a challenging proposition, given the uncertain future of FHIR in the TEFCA framework). An ONC rule currently in pre-public review explicitly mentions TEFCA alongside a new round of certified health tech requirements. It might be reading tea leaves a bit, but it seems possible that the ONC may soon require that all EHRs participating in that program will have to at least support TEFCA technically (albeit still voluntarily for provider organizations).

The real reality is that small regulatory carrots can help to tick the needle forward, but larger private sector sticks will better do the trick. A well-documented and undeniable fact of products with network effects is that they are sticky and hard to iterate once deployed. Given TEFCA and other frameworks are interoperability products with network effects at national scale, each change and update will be difficult and require firm pushes. Stakeholders looking for the shift to TEFCA to occur need to force existing networks to cut over their members with hard deadlines. Additionally, they can change their policies to only onboard new participants into the TEFCA framework, rather than legacy exchange.

EHR Capabilities and Bulk Data Sharing

Much of the health technology landscape in America has come into being via the ONC’s definition of “a certified EHR.” This definition serves as the main regulatory mechanism for the federal government to use its authority to influence the technology decisions of providers’ private businesses, in that most (but not all) providers are incented to use such software via the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program for hospitals and the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System for eligible professionals unassociated with a hospital.

The nuances, caveats, and exceptqions for each of these programs are articles unto themselves and decidedly out of scope to describe here, but the main takeaway is that the bundle of capabilities defined by ONC are promulgated onto providers with a significant book of CMS business in order to avoid a downward payment adjustment and maximize their reimbursement.

The most impactful prescriptive provisions of the ONC Cures Rule were focused on a new round of updates to the ONC’s definition, pushing certified EHRs to create FHIR APIs for patient and population services. This advances things in three ways:

The aforementioned improvement to patient access. While present before, circling the wagons around FHIR R4 makes things a bit easier.

Uniform FHIR integration for business associate applications needing to read data from the EHR (but not write). The advent of EHR API programs is the big shift here, potentially allowing more modern developer experiences.

A net new FHIR export capability for populations of the United States Core Data for Interoperability (USCDI) data set in bulk FHIR format, revolutionizing data exchange for use cases like analytics, pharma, or public health that previously were underserved by transactional flows or custom CSV exports.

These capabilities were required to be available by December 31st of last year, so this year promises to be a fun one as developers explore the limits of EHR documentation, onboarding, and support. Compliance across EHRs seems high on paper (you can search for your favorite vendors here by filtering down to a certification edition of “2015 Cures Update”)

One interesting hurdle and deadline remains outstanding and does not kick in until the end of 2023, however: the Electronic Health Information export. This is a pretty wild capability, requiring that EHRs “enable a user to timely create an export file(s) with all of a single patient’s electronic health information stored at the time of certification by the product, of which the Health IT Module is a part.”

For those unsure about the wildness factor, it’s that all EHI is a heck of a lot of rows in different tables across a hypothetical EHR’s relational database, especially factoring in all the random bespoke modifications across a customer base. The engineering effort to build out this feature is almost certainly a cross-functional nightmare.

It gets crazier. Given that the breadth of EHI stored will almost certainly vary across EHRs and providers, the ONC left the data format and transport method completely up to the vendor. Think of this as the health tech Purge: anything is legal here (so long as it is a machine-readable format). We will see CSVs. We will see JSON. We will see XML. We may see FHIR. The ONC even goes out of its way to mention that PDFs (!!!) can technically be machine-readable and thus are not proscribed (a hundred dollar word for “prohibited”).

So while this capability will certainly advance the ball in terms of data access, you should expect the unexpected - EHR vendors are certainly going to take some novel, fun approaches here.

Lastly, based on an ONC fall agenda item that has slipped into 2023, we can expect a new round of EHR certification criteria this coming year: The rulemaking would also include proposals for new standards and certification criteria under the Certification Program related to the United States Core Data for Interoperability, real-time benefit tools, and electronic prior authorization.

One can only imagine the feeling for EHR vendors having just crossed the compliance finish line and started to breathe a sigh of relief.

Information Blocking

The handwaviest aspect of the ONC Cures Rule, information blocking, was largely intended to not solve any particular problem, but to lubricate all aspects of the creaky wheels of data exchange by giving more levers for people to pull in the event a bad actor was blocking valid sharing. Aimed at providers, certified health IT vendors, and providers (but notably not payers), it was heralded by many of health tech’s Nostadamus-like seers to be revolutionary as different associated deadlines came and went in 2021 and 2022.

This past October, we passed the final date associated with Information Blocking (expanding the definition of Electronic Health Information to mean, well, all Electronic Health Information), so why are we still including it here?

That is in fact because the alluring dream and promise of information blocking provisions curing all interoperability woes lives on! Unmentioned in many announcements and while the rule has existed and been implemented, the actual enforcement and penalties are still not totally determined. The ONC has plans to rectify that this year, formalizing the process and punishment for any bad providers withholding data.

The jury is still out on information blocking, but as this regulatory foundation hardens and gains teeth, it does seem inevitable that there’s an impending whirlwind of actors suing other actors and lots of debates around the exact definitions and exceptions. In 2023 and beyond, we’ll see the tribal knowledge and de facto rules of engagement defining the exact contours and true borders of information blocking arise by the realities of the individual outcomes of those debates.

Prior Authorization

Much maligned, prior authorization is one of the main healthcare punching bags of our era. It is a huge administrative burden, with providers or their staff forced to play phone tag with various payers just to get the care they believe they need for their patients. What’s worse, various parties argue that it results in bad patient outcomes, leading to treatment abandonment or even serious adverse events.

In a hypothetical world, though, prior authorization could be a good process aiming to support evidence-based care and ensure plan affordability through lower premiums. The ONC and CMS seem willing to make the bet that we can get to that ideal world, as recent regulatory pushes on both sides attempt to remove or reduce the aforementioned administrative friction between payers and providers:

CMS-9123-P, Reducing Provider and Patient Burden by Improving Prior Authorization Processes, and Promoting Patients’ Electronic Access to Health Information was proposed in December 2020. Among other things, it proposed a complex series of FHIR interactions for healthcare providers to determine information about coverage requirements (CRD), fill in documentation correctly (DTR), and finally asked for Prior Authorization. It also proposed a Provider Access API in order to arm physicians with relevant clinical information that the payer might have when making decisions. With the change of administrations, however, this languished and was shelved in summer 2021.

A year ago, the ONC’s Request for Information on Electronic Prior Authorization Standards, Implementation Specifications, and Certification Criteria picked back up the prior authorization mantle and focused in on the transactions detailed in the CMS Proposed Rule, asking the industry whether those capabilities were the right ones. In particular, you can sense the ONC trying to decide whether the FHIR implementation guides were mature enough or if legacy approaches using clinical documents (CDA) might be simpler.

Last month, the CMS went back to the well and revived their old prior authorization content for payers in new proposed rule form with the much pithier CMS-0057-P, Advancing Interoperability and Improving Prior Authorization Processes Proposed Rule. It is functionally the same, except that timelines extend until 2026. It also recommends (but does not require) the FHIR implementation guides from above.

As mentioned in the EHR certification section above, new certification requirements are coming, including prior authorization capabilities.

All in all, it’s very clear that the federal government desperately wants to get electronic prior authorization rolled out to both providers and payers as much as possible (although oddly only for items and services and not for medications). With deadlines not kicking in until 2026, there is quite some time on the clock, but the work entailed should not be underestimated.

If I’m a payer who struggled with compliance in regards to the extremely basic Provider Directory or Patient Access APIs, I’m going to have a hell of a time trying to build or configure the exponentially more complex coverage requirements discovery and documentation template APIs. In this coming year, we’re interested to track the perspective of the long tail of smaller payers, who generally lack the means and internal knowledge to absorb the shock of continued regulation (perhaps giving opportunity to young digital health companies to provide value there).

Price Transparency

Caveat: In practice, these subtopics are all very much intertwined, but for the sake of simplicity and clarity, we decided to break them out separately. For an explanation of how this all comes together and a deep dive on an exciting venture being built around it, we highly recommend this read by Nikhil Krishnan.

Hospital Price Transparency

First, some background:

The hospital price transparency rule, which went into effect on January 2, 2021, requires hospitals to provide healthcare consumers with clear, accessible pricing online without requiring personal identifying information. Importantly, this rule is aimed only at hospitals – not all providers – so it's really just a subset of care one receives.

To comply with the rule, hospitals must provide accurate, complete pricing information online in two different ways: (1) in a machine-readable file that details the discounted cash prices and negotiated rates (by each payer and plan) for all items and services offered, and (2) in a price display of at least 300 shoppable services in a consumer-friendly display or a price estimator tool.

The idea, in theory, was that this would empower consumers to find the best quality care at the lowest possible price, and over time, benefit from lower costs driven down by competition. (Side note: last month, the Department of Labor announced that health insurance costs rose by 20.6% y/y… nearly 3x inflation!).

Two years in, the regulation’s effectiveness is being called into question as concerns grow about widespread noncompliance, lax enforcement, lack of price disclosure standards, and exploitation of the “price estimator” loophole.

Several groups have attempted to quantify hospitals’ performance against the rule and have come to wildly different conclusions (an explanation for some of the differences can be found here). For example, a Patient Rights Advocate study of 2,000 hospitals found that only 16% had posted complete machine readable files in compliance with the rule. A couple months later, Turquoise Health’s study of 6,000+ hospitals reported that 65% had posted machine readable files, more than half of which were mostly or entirely complete.

The concern – put bluntly – is that hospitals could be willfully ignoring the rule “to continue profiteering off patients by keeping them in the dark about prices.” And while CMS has issued hundreds of warnings, it’s only fined two hospitals for noncompliance so far. So the perceived threat of penalty is relatively low. It’s important to note, however, that “even this meager response shows the power of enforcement. The two penalized hospitals quickly became compliant and posted exemplary pricing files,” according to Forbes.

While there certainly could be some of that going on, the more predominant hindrance seems to be the high cost and complexity involved with implementation – and as is typical for any new regulation – lingering confusion about the rule’s semantics. KLAS’ survey of hospital RCM leaders found that “many organizations are not investing beyond the bare minimum requirements, and they don’t plan to do more until there is further clarity around the regulations and the expectations going forward.”

Notably, in a move lauded by third-party data consumers, CMS did release a set of recommended MRF schemas last November. Though a universal formatting standard hasn’t made its way into the mandate, the announcement marks a step in the right direction… that is, away from the “wild west” that existed before it.

Transparency in Coverage

The Transparency in Coverage rule is meant to serve the same purpose (as the hospital price transparency rule) but it addresses it from the payer’s side.

The rule requires health insurers to publicly disclose the following information via machine-readable files (MRFs) as well as internet-based price comparison tools (or on paper upon request):

The negotiated rates for in-network providers

The allowed amounts for out-of-network providers

The cost-sharing amounts (e.g. deductibles, copays, coinsurance) for specific services

A list of the specific services for which cost-sharing information is available

Unlike the hospital price transparency rule, which applies only to hospitals vs. all providers, the transparency in coverage rule applies to nearly all payers (health insurers and group health plans, including self-funded clients).

CMS has outlined a phased approach to enforcement:

Payers were required to comply with the MRF requirements beginning July 1, 2022, but they had until January 1, 2023 to implement the online cost estimator tools. Initially, the tools have to provide estimates for a minimum of 500 “shoppable” services. But beginning 2024, that expands to all covered drugs and services.

Compared to hospitals, payers have more sophisticated data sets and are considered much better positioned to meet the transparency rule’s requirements. And so far, the data reflects that sentiment. In its “2022 Price Transparency Data Year in Review” released in December, Turquoise said it had already collected 630 terabytes of payer data. That compares to 3 terabytes of hospital data, despite the hospital’s rule being in effect for 4x as long.

No Surprises Act

The No Surprises Act (NSA) – passed in 2020 and effective as of January 1, 2022 – is meant to shield patients from surprise medical bills. Since it supplements state surprise billing laws, both the federal and state governments have a role in enforcing the law’s provisions.

At its core, the NSA sets limits on the amount healthcare providers can bill for out-of-network services (details below):

No balance billing for out-of-network emergency services

No balance billing for non-emergency services by out-of-network providers during visits to certain in-network facilities (unless notice and consent requirements are met)

No balance billing for covered air ambulance services by out-of-network providers

In instances where balance billing is prohibited, cost-sharing for insured patients is limited to in-network levels

It also requires a provider or facility to give an uninsured or self-pay patient a good faith estimate (GFE) of expected charges at least 3 business days before a scheduled service. For a patient enrolled in a group health plan, group or individual insurance coverage offered by a health insurance issuer, a federal health care program, or a Federal Employees Health Benefits plan, the provider or facility has to submit the GFE to the plan/issuer, which then has to send an advance explanation of benefits (AEOB) to the patient.

Separately, the Act establishes a process for resolving disputes between providers and insurers over the cost of out-of-network care. If they can’t come to an agreement, they can enter an independent dispute resolution (IDR) process by which a neutral third party reviews and settles the dispute. At a high level, that process looks something like this:

The federal IDR portal launched in April 2022. In the first 5.5 months, HHS said it received over 90,000 claims, which was more than 5x the volume it expected for an entire year. And determining which disputes are actually eligible for review is taking much longer to process than initially anticipated. So far, just 4% have ended in payment. A massive backlog is piling up as a result.

The IDR provisions continue to be a major source of contention between payers and providers, as well as fruitful fodder for litigation. The Texas Medical Association has already filed three lawsuits challenging the NSA – and some health tech folks we spoke with think it may even make its way to the Supreme Court. Regardless how that plays out, we expect to see a lot more drama on this front this year. Buckle up.

Privacy

Online Tracking Technologies

Healthcare entities’ use of online tracking technologies (e.g., cookies, web beacons, pixels, etc.) has been a growing area of concern for some time now, but it may have just reached its boiling point. Last year, there was an absolute tidal wave of bombshell media investigations, congressional hearings, and lawsuits over the practice.

Here are just some of the headlines:

Mounting pressure finally prompted The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) to issue some guidance in December. Here’s what it had to say.

It clarified that individually identifiable health information (IIHI) collected on regulated entities’ websites/mobile apps will, in fact, qualify as protected health information (PHI) and therefore be regulated by HIPAA. Importantly, that applies to all IIHI even if it’s not specific treatment or billing information and even if no relationship exists between the patient and regulated entity.

Why? According to OCR, “when a regulated entity collects the individual’s IIHI through its website or mobile app, the information connects the individual to the regulated entity (i.e., it is indicative that the individual has received or will receive health care services or benefits from the covered entity), and thus relates to the individual’s past, present, or future health or health care or payment for care.”

There’s a distinction, however, between user-authenticated web pages (e.g., only available to patients or plan members) and unauthenticated web pages (e.g., accessible by anyone). Information on user-authenticated pages will be treated as PHI and be subject to HIPAA. Okay, great, that’s clear. But for unauthenticated pages… not so clear. Most of the time, trackers on these pages don’t ever access PHI and therefore aren’t too much of a concern. But there are situations where they could, and in those cases, HIPAA rules would apply.

OCR called out two specific examples (though there are certainly others):

Though clarity was the intent, all that’s really clear from this guidance is that OCR has a much more expansive view of PHI than many anticipated. That could make it more difficult for regulated entities to determine exactly what their compliance obligations are and fulfill them in a timely manner.

It’s important to keep in mind that this is totally new territory for HIPAA regulated entities, especially providers. Providers have long understood the HIPAA requirements for their EHRs, practice management systems, and clinical support software, but online tracking technologies are entirely different beasts that they’ll have to learn to tame.

Hopefully, in time, more guidance will bring more clarity. But with public awareness growing and litigation escalating, healthcare companies don’t have time to waste. Today, regulated entities should be taking steps to:

Assess the use of tracking technologies on their websites and mobile apps

Evaluate whether HIPAA breaches have occurred (and fulfill the breach notification obligations, if so)

Ensure business associate agreements (BAAs) or patient authorizations are in place for any PHI shared via online trackers with third-parties

Post-Dobbs Considerations

Another development worth mentioning is the Supreme Court’s ruling on Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade. While it’s largely a state (vs. federal) matter, one implication of particular concern is patient privacy afforded under federal law (HIPAA).

As currently written, the HIPAA statute has several gaps and gray areas that may unintentionally leave abortion patients vulnerable to law enforcement. OCR issued some guidance, but privacy advocates argue it’s not enough as health care providers can still be compelled to disclose patient data (revealing who sought and/or received an abortion) under special circumstances, such as a subpoena or court order.

HIPAA also only applies to regulated entities, which include health insurers, providers, data clearinghouses, and associates. But it can’t protect patient information gathered by the 2,500 “crisis pregnancy centers” that attempt to attract and redirect abortion-seekers.

And then there’s all that consumer-generated data that falls outside of HIPAA’s purview: someone’s search history, text messages, geolocation data, or info they entered into a period-tracking app. All of that can be used as evidence against them in court.

Several bills have been proposed to address these concerns, but very few have had real inertia. The one exception is the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA).

The ADPPA – which was moved out of the House last year with an “impressively large bipartisan vote” (53-2) – is the closest the US has ever come to passing a comprehensive consumer data privacy law. If passed, the ADPPA would apply to any information in the hands of non-HIPAA-entities “that describes or reveals the past, present, or future physical health, mental health, disability, diagnosis, or healthcare treatment of an individual.”

Telehealth Flexibilities

Originally, were set to expire along with the public health emergency (PHE). Each time the PHE got extended, so too did the flexibilities. As more time went on, telehealth became more ingrained in the way Medicare providers delivered and beneficiaries received care. And the threat of a “telehealth cliff” at the end of the PHE became a much scarier possibility. So in Q1’22, legislators extended some of the flexibilities for an additional 5 months post-PHE. Though it was an improvement, many stakeholders remained frustrated that the flexibilities were still so tightly anchored to the PHE timeline.

That changed just recently, with the signing of the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2023 (omnibus bill), which gave a number of telehealth flexibilities the green light through December 2024 – irrespective of when the PHE ends. Those flexibilities include:

An expanded definition of “originating site” to include any site where an eligible patient is located, including their home.

An expanded list of eligible practitioners to include occupational and physical therapists, speech-language pathologists, and audiologists.

Coverage and payment for audio-only telehealth.

A postponement of the 6-month, in-person requirement for telemental health services.

The ability for FQHCs and RHCs to serve as distant sites and provide telehealth services.

The ability to use telehealth to meet the face-to-face recertification requirement for hospice care.

The law also gives employers and health plans two more years to provide pre-deductible coverage of telehealth services for individuals and families with high deductible health plans coupled with health savings accounts. The HHS Secretary will be required to submit utilization reports to Congress with the interim report due October 2024 and the final due April 2026.

While these are certainly steps in the right direction, telehealth advocates continue to fight for more permanent reform.

Hospital-at-Home

The omnibus bill may also be a boon for the hospital-at-home movement.

By way of background, hospital-at-home is a care model that allows acute and post-acute patients to be treated from home instead of in a traditional hospital setting. The model itself has been studied for decades and has demonstrated potential in improving patient outcomes, increasing patient satisfaction, and reducing costs (vs. inpatient hospitalization).

Despite these potential benefits, significant regulatory and reimbursement barriers have prevented the hospital-at-home model from being implemented broadly across the US.

Those barriers were temporarily lowered during COVID-19, when CMS launched the Acute Hospital Care at Home (AHCAH) initiative. Under AHCAH, eligible hospitals could apply for CMS waivers that, if approved, would allow them to get paid – at the same rate as inpatient care, under Medicare FFS – for delivering hospital-at-home services during the public health emergency (PHE).

Originally set to expire along with the COVID-19 public health emergency (January 11, 2023), the AHCAH waivers will now be extended through December 2024, thanks to a provision in the recently signed omnibus bill. Since AHCAH’s launch in November 2020, more than 250 hospitals have obtained waivers.

But getting approved by CMS and getting a hospital-at-home program off the ground are two entirely different things. Hospital-at-home expert Dr. Bruce Leff estimates that only half of the hospitals that obtained waivers have actually started treating patients at home.

Why? Well, implementing a hospital-at-home program is an incredible undertaking. It requires a tremendous amount of time, capital, labor, and perhaps most importantly, culture change to be successful.

According to Dr. Leff: “HaH is a countercultural care delivery model, a square peg in the round hole of health service delivery whose structures and processes are hard-wired to provide facility-based care. Implementation of HaH requires significant culture change and change management to be successful, and there has been a strong appetite for technical assistance from health systems as they build their programs. Building a HaH requires building a virtual hospital unit with fully replete supply chains and logistics management to assure highly reliable, high-quality, safe care.”

It’s a huge investment to make. So that combined with other challenges (e.g., deepening financial losses, rising inflationary pressures, workforce shortages, supply chain disruptions, etc.) has made many hospitals hesitant to take the leap without any guarantee that the program will exist permanently.

But legislators want to see a lot more data first. Which is why – along with the two-year waiver extension – the recently signed omnibus bill requires the HHS Secretary to conduct a study (and publicly report its findings by September 30, 2024) on the following:

The hope is that two more years of data from the program would be compelling enough to inspire more permanent support from CMS (via legislation)… or, at the very least, support another 1-to-2-year extension of the waivers, at which point more permanent action could be taken.

Online Prescribing of Controlled Substances

Online prescribing continues to be a hot button issue due to fears about controlled substances and potential for abuse. Unfortunately, a combination of regulatory and legislative policy is needed to properly address these concerns. And we’re potentially running out of time to make that happen.

Here’s why.

When the Ryan Haight Act was passed in 2008, telehealth was not a main avenue of healthcare delivery. The problem Congress was trying to solve at that time was the illegal prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances via the internet. In response, Congress required Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)-licensed practitioners to evaluate patients in person first before prescribing a controlled substance.

The law recognizes telemedicine but requires the DEA to establish a “special registration” process via regulation. To date, the DEA has not done so.

Covid-19 fundamentally changed that by prompting the Drug Enforcement Administration to waive the Act’s in-person requirements.

At a very high level, patients and providers have noted substantial benefits from this expanded access. And aside from some specific and highly publicized allegations (e.g. Cerebral), there’s been little evidence that the public health emergency relaxations have led to broad-based diversion and abuse. In fact, according to the Alliance for Safe Online Pharmacies, studies have shown that restricted access and shortage of prescription drugs can actually increase the likelihood of those outcomes.

But unfortunately, the public health emergency waiver will inevitably end, putting millions of patients at risk of losing access to the legitimate and necessary care they got accustomed to during the pandemic.

A more permanent solution is needed, and it actually could be accomplished without Congressional action. As mentioned previously, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has the statutory authority to establish a special registration process, which may allow licensed telehealth clinicians to bypass the Ryan Haight Act’s in-person requirement.

Back in March, more than 70 organizations including the American Psychiatric Association and the American Telemedicine Association urged the DEA and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to get the ball rolling.

Now, 9 months later, there’s been very little progress.

And there’s growing concern that there could be a material time gap between the end of the public health emergency waiver and the DEA taking action. During that gap, any virtual care company or provider remotely touching the Ryan Haight Act could be in for a rude awakening.

(Hat tip goes to Two Doctors and a Stack. Their deep dive on this topic is excellent.)

That’s not an immaterial segment of the market. Tons of virtual care startups —particularly those specializing in telepsychiatry and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) — were able to take advantage of these temporary relaxations and, accordingly, raise large sums of capital to expand those business lines over the last few years. Now those businesses could be at risk.

The other issue with reverting back to the Ryan Haight Act at the end of the public health emergency is that it doesn’t effectively address the more threatening byproduct of the internet era: the illegal sale of controlled and counterfeit controlled substances.

The worst case scenario, according to Faegre Drinker’s Libby Baney, is that the DEA fails to create a special registration process before the PHE waiver ends, we hit the ‘cliff,’ and patients lose access.

“Patients who need controlled substances will find a way to get treatment,” she said. “We’ve seen this over and over again. Cutting off access to needed medicines doesn’t stop demand; it just pushes patients to alternative, riskier, gray market sources. The open, international, and mostly unregulated internet is the natural (and proven) outlet for patients looking for access to medicine.”

But what keeps her up at night is knowing how flooded the internet is with counterfeit medicines – potentially laced with deadly fentanyl or other toxins. If the DEA fails to act, Baney predicts “more Americans will start using illegal online drug sellers (via websites, social media platforms, marketplaces) to buy controlled substances and end up untreated or worse, dead, due to bad meds.”

One potential solution being proposed is the DRUGS Act, which aims to shut down illegal online sales without restricting patients’ access to otherwise legitimate telehealth and online pharmacies. Similar to the domain name registration transparency issues mentioned previously, the DRUGS Act would target some of the practices of domain name registrars (e.g., GoDaddy).

Medicaid Redeterminations

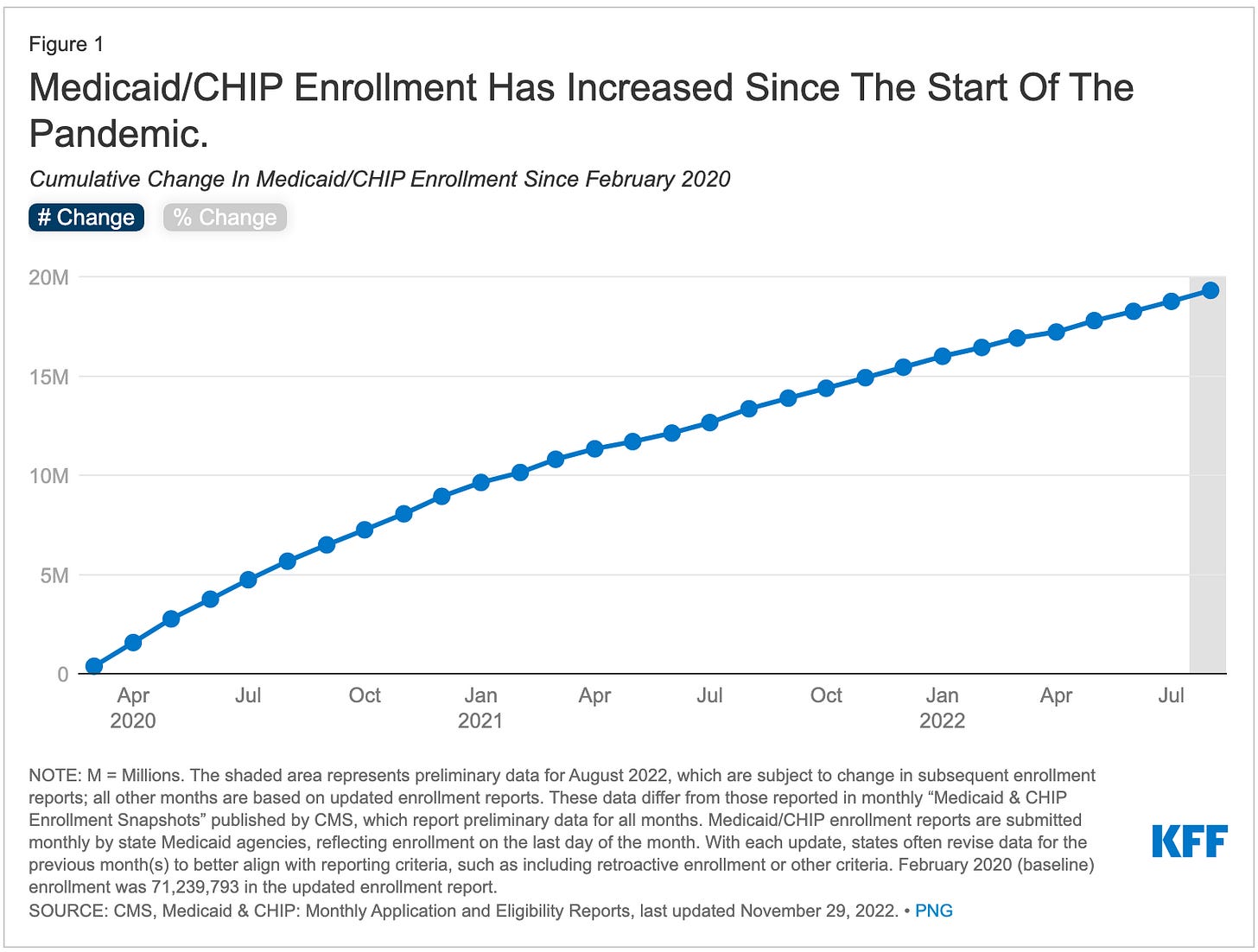

As a reminder, at the beginning of the pandemic, the federal government put a pause on Medicaid redeterminations to ensure beneficiaries maintained coverage throughout the public health emergency (PHE). By law, state Medicaid programs were required to keep their members continuously enrolled all the way through the last month of the PHE. In exchange for meeting this requirement, they would receive enhanced federal funding.

As a result, Medicaid enrollment has grown substantially to a record high of 90.6M individuals (more than 25% of the population) by August 2022.

But when the PHE expires (currently set for January 11, 2023), the continuous coverage requirement will end. Under the recently signed omnibus bill, states can start processing Medicaid redeterminations on April 1, 2023 and will have one year to complete them. During this time, they’ll begin disenrolling people who no longer qualify or who fail to respond to requests for information.

HHS estimates 15M people will lose coverage as a result. About one-third should qualify for tax credits for ACA marketplace insurance and could reasonably transition over there. Others may qualify for employer-sponsored insurance.

Administrative barriers could cause close to 7M people to lose coverage even though they’re still eligible, says HHS. To minimize that risk, the new law requires states to have the most up-to-date contact information for enrollees and to make good faith efforts to contact them (using more than one communication method) about redeterminations.

ACO REACH

TL/DR: ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) is the redesign of the Global and Professional Direct Contracting (GPDC) model. The program just formally kicked off on January 1, 2023 and is set to run through 2026.

Background on GPDC:

The GPDC is a payment and delivery model that was introduced by CMS in 2020 as part of the Next Generation Accountable Care Organization (ACO) initiative. GPDC, which launched April 1, 2021, was designed to improve uptake of value-based care models, encourage care delivery innovation, and give ACOs greater flexibility in how they provide care to their patients.

53 Direct Contracting Entities (DCEs) participated in 2021, including 29 “standard” (e.g., VillageMD, Clover), 18 “new entrant” (e.g., Iora Health, Oak Street Health), and 6 “high need” (e.g., Assurity, Renovis Health) providers. For a deep dive on performance, I highly recommend Blake Madden’s breakdown here.

Fifty of the original 53 DCEs – as well as 49 new participants – participated in 2022. Performance metrics haven’t been reported yet.

But in February 2022, after collecting stakeholder and participant feedback on GPDC, CMS redesigned and renamed it to ACO REACH. The redesign reflects three priorities that CMS believes will improve care for beneficiaries, address health equity, and better inform the Medicare Shared Savings program:

Advancing health equity to bring the benefits of accountable care to underserved communities

Promoting provider leadership and governance

Protecting beneficiaries and the model with enhanced participant vetting, monitoring and greater transparency.

(For a more detailed overview of the policy changes, check out this table).

Overall, the ACO REACH model is meant to test how providers can be incentivized to collaborate across multiple treatment plans, spend more time with patients with complex, chronic conditions and, ultimately, improve health outcomes. ACOs that participate are expected to deliver high-quality, coordinated care.

In August, CMS announced it had provisionally accepted 110 applicants (at <50% acceptance rate), including 71 “standard” ACOs (e.g., Aledade, Pearl), 19 “new entrants” (e.g., Homeward, Main Street Health, One Medical), and 20 “high needs” providers (e.g., Vytalize Health, Upward Health).

As far as preexisting GPDC participants go… They were allowed to transition to ACO REACH provided they maintained “strong compliance records” for 2022 and met the new model’s requirements by January 1. CMS also invited 34 ACOs to participate in an “implementation period” running from August through December 2022. Starting January 1, those ACOs also had the opportunity, but not the obligation, to transition into ACO REACH if they met the model’s requirements.

But a group of lawmakers is calling CMS’ participant screening criteria into question and raising concerns about potential for fraud and abuse. In a recent letter to CMS, the politicians called attention to the large number of PE- and investor-controlled DCEs (which, they argue, are highly profit-motivated), 10 of whom have documented histories of healthcare fraud.

“The ability of organizations with known histories of fraud and abuse to take part in the program increases the risks for Medicare beneficiaries, and raises concerns that CMS screening procedures for participants are inadequate, putting taxpayer dollars at risk. We respectfully ask the agency to reevaluate the decision to allow these DCEs to participate in the program,” the letter read.

The lawmakers also asked CMS to provide written responses to several questions – primarily related to its screening methods – by January 16, 2023.

Network Adequacy

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), health insurance plans must meet certain requirements to be considered qualified for sale on the federal exchanges (and, accordingly, deemed a “qualified health plan,” or QHP).

One of those requirements is having an adequate provider network, meaning one that’s sufficient in size and scope to meet the needs of plan enrollees without “unreasonable delay.” As part of that, they’re required to contract with a certain number of essential community providers (ECPs). ECPs are healthcare providers that serve predominantly low-income, medically underserved individuals (e.g., FQHCs, rural health clinics, and other safety-net providers).

Before the ACA, states had complete regulatory oversight of private health plans’ networks, with rules and compliance varying widely from state to state. What the ACA did was establish a minimum federal standard for network adequacy for the first time, entitling all marketplace enrollees – irrespective of state – timely access to providers they need. Unfortunately, very few states updated their network rules to match the federal model. And eventually the Trump administration eliminated the federal requirements and oversight entirely.

The Biden administration has since resumed federal oversight and has even begun rolling out additional requirements to strengthen the standards.

Beginning this year, CMS will evaluate QHPs for compliance with network adequacy standards based on time and distance standards, and next year, appointment wait times. The new regulations specify that an “adequate network” must provide reasonable access to care for 47 speciality types, nearly 5x the previous requirement of 10. The threshold for ECP participation also changed this year, increasing from 20% to 35% of available ECPs in a QHP’s service area. For 2024, CMS has proposed adding two new ECP categories: substance use disorder treatment facilities and mental health facilities.

Many plans are rushing to catch up to the new, more stringent standards after several years “off.” J2 Health recently reviewed 250+ carrier networks and found that 80% weren’t meeting the new requirements. The average network failed to meet 15% of the required county-specialty pairs, and in some states, networks were failing 30% of the requirements.

CMS also sets network adequacy standards for plans that operate in Medicare Advantage (MA) and the Medicare Prescription Drug Program (Part D). Starting with the 2024 contract year, applicants must demonstrate – and not just attest – that they have an adequate network before CMS will approve an application for a new or expanded MA plan. This significantly raises their risk of denial. CMS also proposed a number of network adequacy amendments to improve access to behavioral health services.

“To be compliant with new adequacy standards, plans using traditional adequacy processes will need to invest more resources into their network strategy,” says J2. But “strict medical loss ratio (MLR) standards and new price transparency regulations leave payers wondering how they can achieve both.”

Medical Device Security

(Editor’s note: a BIG thank you to Kelly Watson, VP Product & User Experience at Tidepool, on this section)

Following increased focus on cybersecurity at a federal level, and a draft guidance doc published in April 2022, the recently signed Consolidated Appropriations Act 2023 (omnibus bill), includes provisions mandating that medical device manufacturers ensure that their devices meet certain cybersecurity requirements. Provisions of this bill align closely with the Medical Device Safety Action Plan published in 2021 and the Patch Act passed in 2022.

The FDA has been strongly encouraging medical device manufacturers to take action to ensure the cybersecurity of their devices across the product life cycle. Draft guidance outlined the strong product development lifecycle and threat modeling processes necessary to develop secure devices, including devices that are considered Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) in order to prevent unauthorized users from accessing data or controlling the device.

What this legislation now provides for the FDA is explicit authority and oversight to enforce requirements for new sponsors. Medical device submissions must now provide sufficient evidence of cybersecurity controls and the plan for how to identify and address vulnerabilities discovered postmarket.

Four key takeaways for new sponsors:

Sponsors are now required to submit a cybersecurity plan on how the sponsor will monitor, identify, and address postmarket cybersecurity vulnerabilities and exploits, including vulnerability disclosure.

Sponsors must now also submit a software bill of materials (SBOM) including off-the-shelf, open-source, and commercial components.

Sponsors must demonstrate design, development, and maintenance processes and procedures to ensure that the device and related systems have appropriate cybersecurity controls. While not explicitly described, demonstration of appropriate verification and validation of security controls through boundary testing and penetration testing to identify and exploit vulnerability in the device is expected.

The act also includes forward-looking requirements to make available postmarket updates and patches to the device and related systems to address vulnerabilities that could cause uncontrolled risks.

New regulations will take effect 90 days after the date of enactment of the Act. To note, for those sponsors currently under review, an application or submission submitted before the effective date is not subject to the new requirements.

What’s next:

The legislation also provides the FDA roughly $5 million in funding to continue to help expand the medical device cybersecurity regulatory efforts.

Draft guidance will also be confirmed and published in the next two years.

While these are certainly steps in the right direction, we hope to see the FDA use its influence to ensure further controls do not limit data access.

At a very high level, device manufacturers have historically thought of device data as owned by the device manufacturer. Thousands of patients, providers and organizations provided comments on the draft guidance asking FDA to put in mechanisms to ensure device manufacturers do not use cybersecurity mitigations as a mechanism to prevent authorized users from accessing therapy data or from controlling their own devices. Fortunately, several device manufacturers of hardware and cloud-based systems have set excellent precedents on how to follow a Secure Product Development Framework (SPDF) as described in the draft guidance and support properly authenticated individual patient users' access to their data.

Additionally, we hope to see FDA provide specific guidance in support of sponsors shifting away from locked down devices, and proprietary communication protocols and authorization services as the only way to secure devices, such as:

Utilization of open standards such as ISO/IEEE 11073-40102 and corresponding Bluetooth LE implementations of these communication protocols and authorization controls.

Developing cybersecure medical devices on mobile platforms. iOS and Android-based SaMD platforms and bring your own device (BYOD) iOS and Android-based controller systems are uniquely positioned to support rapid testing, evaluation, and patching vulnerabilities discovered postmarket.

Both areas have the potential to drive further innovation and facilitate the development of interoperable, plug-and-play systems, similar to those commonly seen in the consumer electronics industry. What will be interesting to see is how multi-vendor and interoperable systems collaborate to implement and achieve effective cybersecurity measures through open interoperability standards and postmarket coordination.

In addition to the current draft guidance, sponsors can find additional resources below:

Mitre’s cybersecurity playbook

MDIC’s threat modeling playbook

MedCrypt’s threat modeling white papers

MedCrypt’s recent article by Naomi Schwartz and Axel Wirth

FDA x Software as a Medical Device (SaMD)

In 2017, the FDA proposed the idea of a Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program that would serve as a new regulatory pathway for SaMD products. The idea was that participating companies would be evaluated based on their overall approach to product development rather than on a product-by-product basis. This would allow them to bring new, innovative software products to market much more easily than through traditional pathways.

Over the last 5 years, the FDA has been testing the feasibility of the program in a small pilot with a handful of developers. But in a September report, the FDA ended the pilot, conceding the agency lacks the statutory and regulatory authorities needed to implement the program as originally intended.

“Based on these observations from the pilot, FDA has found that rapidly evolving technologies in the modern medical device landscape could benefit from a new regulatory paradigm, which would require a legislative change,” the agency said.

Next steps, however, are a bit of a question mark. The FDA provided no details on what additional authorities it would need to make the Pre-Cert program a reality.