The wild and magical world of claims

All aboard healthcare's financial data train 🚂🚂🚂

Going to be at ViVE 2024 in Los Angeles next week? The Flexpa team will be too. Reach out if interested to meet and chat all things claims data:

In the year 1996, Quad City DJs released their hip-hop anthem “C'Mon n' Ride It (The Train)”. As different musical artists across the US have started to get involved in healthcare unexpectedly, we at Flexpa called them up to lay down a new track for us on the latest and greatest train: claims data.

Come on, access the claims, hey, unlock it

Come on, access the claims, hey, unlock it

Come on, access the claims, hey, unlock it

Come on, access the claims, hey, unlock it

Ah, ah, ah, ah, ah

I know I can code, I know I can code, I know I can code, I know I can code

Ah, ah, ah, ah, ah

I know I can code, I know I can code, I know I can code, I know I can code

Deep in healthcare, where we hold this role

It's those Data Teams and you, we aim for patient control

So if you wanna sift through medical claims

Just log on to the EHR frame

We're gonna filter, ooh, HIPAA-compliant go, folks

So get your clinicians, and your data scientists too

Queue it up now

Click, click, dive into this, click, click

Hey, no need to hesitate, let's improve patient care

I aim to bring you insights, to diagnose with flair

If you're cautious on privacy, let's make it worthy

Don't be skeptical, until you've analyzed it

So to all healthcare orgs, know I'm mentioning your game

The atomic unit of healthcare financials in America, the claim, is a much maligned and somewhat mediocre instrument for its core purpose (facilitating payment to a provider by an insurer for services rendered). It’s unfortunately coupled by law (not regulation) to an outdated and archaic standard, X12, that purposefully buries their documentation behind paywalls. Does it work? Most of the time. Do we deserve better? Absolutely.

However, beyond that primary application for transactional exchange, the claim is actually a fantastic tool for understanding a patient’s health. Claims document all the touchpoints a patient has had with the healthcare system and include the core data of care that occurred - diagnoses, medications, procedures, and care team. In contrast to provider-sourced clinical information, they also show the financial layer, which can be crucial for various analytical tasks—be it cost optimization, compliance checks, or risk assessment. Perhaps most importantly, claims are also highly standardized relative to almost all other healthcare data sources, due to the congressionally mandated use of X12 and associated code systems.

When it comes to health data, whether provider, payer, or wearable, there are three fundamental barriers when it comes to really understanding a patient’s health:

Fragmentation: Care occurs in many places, and those places are siloed. Building the trust and confidence between competitors at a regional or national scale to pool in a centralized fashion or share in a networked fashion is a challenging proposition.

Access: Health data is sensitive. Therefore, the laws and regulations around health data are restrictive in who can view health data (based on role or purpose of use). Even if fragmentation is solved, not every role that wants to help a patient has the privilege of doing so.

Completeness: Compared to data from other industries, health data is wildly complex in structure and variety. Even when fragmentation and access are solved for specific roles, some data types may be missing.

Here's where claims come in. They tackle the first barrier of fragmentation head-on. You see, a patient might have multiple healthcare providers, but they usually have just one payer at a given point in time (aside from edge cases like dual eligibles, veterans, or cash pay scenarios). Claims are the central hub that collects data from all these spokes, effectively centralizing information across a wide and disparate provider landscape.

Additionally, the established paths for claims processing ensure that parties with legitimate roles—such as payers (insurance companies), clearinghouses, auditors, certain healthcare providers, and patients —have the right to access this data, thereby tackling the access barrier. Increasingly, major regulators are pushing to enable a landscape of new API-driven approaches for each of these channels.

However, to most, claims data are an enigma wrapped in a mystery, surrounded by a conundrum, and the routes leading to that data form a labyrinth worthy of Greek mythology. Deidentified and identified data, obscure acronyms, varied formats, and varying purposes of use muddy the waters.

So, let’s enumerate the state of claims and, in doing so, clarify the weird world of healthcare’s financial data.

Types

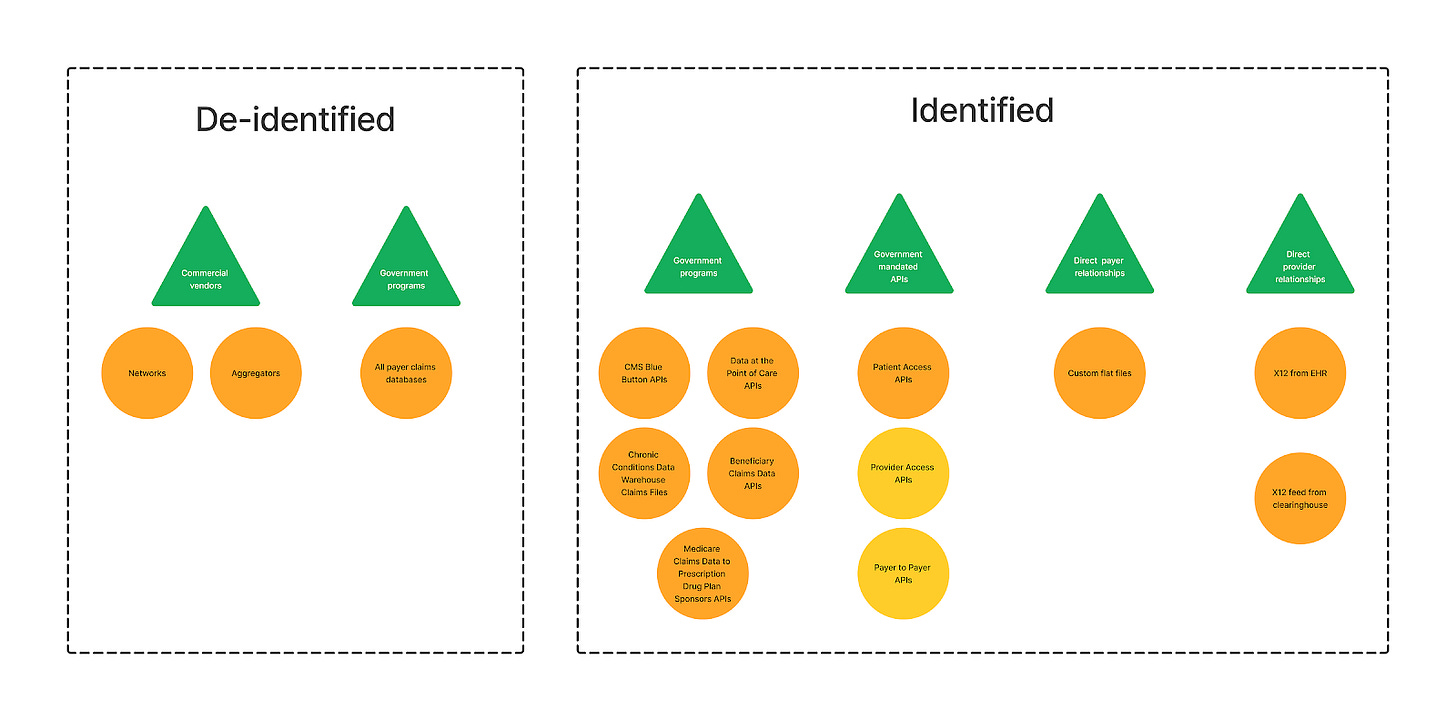

When thinking about claims data, there are two basic patterns of use, driven by what problem a person is trying to solve:

Provision, navigation, and optimization of care for individuals: Claims data for specific patients allows various organizations involved in the chain of care (providers, plans, brokers, navigators, and more) to assist the patient by understanding their health in both financial and broad clinical terms. Identified data is needed/helpful when having substantial patient history is necessary for these tasks.

Identified claims data are needed here - while it’s possible to baseline costs or build optimal care pathways using deidentified data, it’s not possible to help someone without specifically tying the claims to their identity.

Analytics for insights about populations: Given that claims are a well-structured summary of key health data like medications, diagnoses, and procedures, it’s extremely common that organizations want bulk claims to understand trends and compare at a population level.

While identified data is hypothetically possible, it comes with burdensome HIPAA roles and consent considerations.

As a result, de-identified claims data sets are a common tool for this use case, as a much wider variety of organizations (pharma, financial analysts, public health researchers) can accomplish their business goals with considerably less friction and risk using that pathway.

In this piece, we’ll spend a bit more time on the identified paths to claims data, because:

Programs for identified claims access aren’t as well-known or detailed comprehensively, whereas the de-identified data sales space is extremely mature and has excellent write-ups like this one by Datavant

Programs for identified claims access are relatively new and changing thanks to regulation by the CMS

Definitions

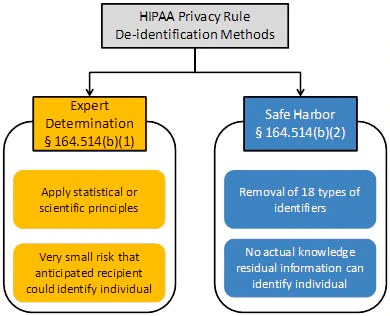

When it comes to de-identification, HIPAA defines two major methods that are worth explaining:

Safe Harbor, is deterministically and definitively de-identified. You are taking the dataset and going over it with a fine-toothed comb to erase any identifiable information, such as names, address info smaller than state, contact information, and patient/member/account IDs. With that information scrubbed, linking to other datasets is nearly impossible (aside from true tail-end edge cases, such as diseases rare enough to uniquely map to a single patient over a span of time). While usable for some high-level, generic analytics, this is not where the major de-identified data businesses play.

Expert determination is the crazy probabilistic cousin of Safe Harbor who plays it fast and loose. Using the power of <hand wave>math</hand wave>, a very smart statistician looks at a dataset to determine if the risk that anyone could use it alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, to identify an individual is small. This is magic of a very high order, with only a few wizards nationwide who are capable of this task. It is also probably more apt to call it pseudonymization - datasets using this path do not have all PHI removed, but instead have it altered, randomized, or generalized. For instance, instead of exact ages, age ranges might be used, or specific geographic locations might be broadened from a street address to a zip code or city. This is significantly more valuable than Safe Harbor for many buyers, in that understanding some of those basic demographics is useful! What age a patient was when they had a condition, what county they lived in, or their gender is all helpful in slicing and dicing the data to get to deeper insights and baselines.

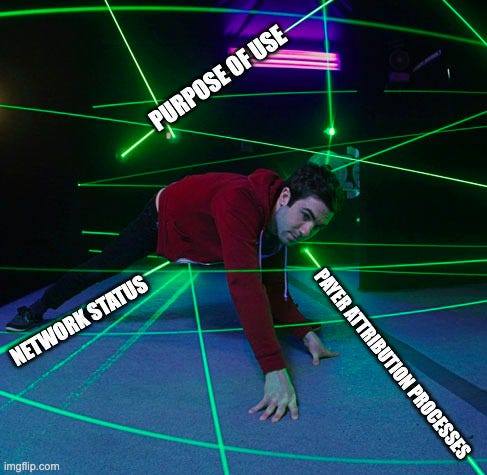

On the identified claims side of things, given claims are Personal Health Information (PHI) under HIPAA, we see certain concepts commonly used across various data access programs that must be understood to ensure appropriate access.

Attribution: the method by which an organization (usually a payer) determines which healthcare provider is responsible for coordinating a patient’s care. This matters regarding claims data access because some data exchange is limited to attributed providers only.

In value-based care models, attribution gatekeeps any payment, so it’s well-defined, although the particular methods and algorithms for attribution vary. In fee-for-service, attribution is less critical, so the logic is thus less defined.

Prospective attribution assigns patients to providers at the beginning of a measurement period, while retrospective attribution does so after the period has ended, based on the care that was actually delivered.

Network status: Whether a healthcare provider is part of a payer's network. This is often a factor in claims data access in scenarios without strong attribution logic.

In-network providers have agreements with payers to provide care to their members at predetermined rates, while out-of-network providers do not have such agreements.

Purpose of use: the reason for accessing PHI, including claims data. HIPAA regulations stipulate that PHI should be used only for specific purposes such as treatment, payment, or healthcare operations.

Even when checking the boxes regarding attribution and in-network status, the reason for data use still matters. A provider pulling claims (or other) data to inform care (Treatment) does not have the same access rights if they were doing it for a marketing campaign or for analytics research (Operations).

With those ideas in mind, let’s dive in.

> Patrick Bateman voice: Look at that subtle transparent blue coloring. The tasteful consolidated length of it. Oh, my God. Just two payers over the same time, spanning seven different providers.

10/10

All good until I hit this line:

"You see, a patient might have multiple healthcare providers, but they usually have just one payer at a given point in time (aside from edge cases like dual eligibles, veterans, or cash pay scenarios)."

It's not just edge cases.

Employers change payers/networks often - and employees are with the same employer for typically less than 5 years. That dual-sided "churning" creates enormous fragmentation - and about 155 million Americans get their coverage through their employer. This is one of the reasons that "administrative complexity" is estimated (2019) to cost our healthcare system ~$266 billion per year.