The Epic Defense: A Legacy of Protected Innovation

How Early Setbacks Shaped Epic's Approach to Partnerships and Intellectual Property

Sometimes when writing, you pick your topic, architect what you want to say, and fill in that blueprint. Other times, you find yourself writing something entirely unexpected - brief asides and digressions develop into a paragraph, expanding into sections and eventually, a full article. This article was intended to be the former - I originally intended to put pen to paper on the topic of this recent Open Forum on Connecting to Epic, as it’s one of the most common questions I receive. However, as an author, I am somewhat incapable of ignoring the shiny object, the story behind the story. In this installment, I’ll take a deeper look into the events and history that shaped Epic into the company it is today.

A summary or explanation of where we are is good, but the why behind how we got here is certainly spicier. And moreover that ‘why’ includes some fun, obscure, and dramatic moments in Epic’s history. Epic’s strategy in regard to developer programs and marketplaces can largely be traced to a few interesting anecdotes. We’ll attempt to peel back the onion and peer into Epic’s psyche. If you’d like straight juice and no tea, though, check out that recent Open Forum, which largely covers the same tactical material waiting in the hopper, or wait for the subsequent article (which I do really hope will be covering those topics).

Even as it grew into the dominant player in healthcare IT, Epic has notably resisted the industry-wide trend toward becoming a true platform company. No direct sandbox access for developers, proprietary API documentation, and until recently, an almost complete absence of direct partnerships - these aren't just arbitrary choices or simple protectionism. Formative events shape Epic along two axes: aggressive defense of their innovations and selective collaboration with outsiders.

Intellectual Property

If you have even a brief familiarity with Epic, you may have noticed an overt (and sometimes aggressive) protectiveness of its intellectual property. If not, a few manifestations of that cultural proclivity:

Taking Patent Trolls to the Woodshed

Not-so-brief Addendum on Patents

The point of this sub-section is not to criticize Epic for its behavior. On the contrary, patents for software are somewhat silly. As a reminder:

Patents: Protect new, useful, and non-obvious inventions, processes, and machines for 20 years.

Intent: to encourage innovation by giving inventors temporary monopoly rights

Copyrights: Protect specific expressions of ideas/original creative works (literary, musical, dramatic, artistic works, photographs, software code) for the life of the creator, plus 70 years (for individual works), not the ideas themselves

Intent: to promote innovation via the creation of artistic and cultural works

Trademarks: Protect brands and distinguish goods/services used in commerce, such as names, logos, symbols, and designs used to identify products/services.

Intent: to convey the goodwill and value developed by the company in the trademark and protect consumers from confusing brands

Patents for software don’t make sense, because software is fundamentally a series of written instructions that express ideas through code, much more akin to writing (which is protected by copyright) than physical inventions (which are protected by patents). Furthermore, the abstract algorithms and processes which underpin software are closer to mathematical formulas or methods of organizing human activity, which have traditionally been excluded from patent protection. The framework articulated by Ben Thompson makes the most logical sense: no patents, full copyright, with APIs explicitly exempted from copyright (and, if you want to get radical, mandatory disclosure and documentation).

I do want to get radical, in fact, but unfortunately, the current state of US intellectual property law in regards to software impedes the ability to get radical. Instead of moving away from patenting software, US law allows some patents on some forms of technology as enabled by the opinion from 2014’s Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International. The test laid on in the Alice Corp. case is, from this amateur armchair lawyer’s* perspective, exceedingly arbitrary - the distinction between something non-patentable, such as basic computer implementations of business methods, and something patentable, such as technical improvements to computer functionality itself, is often unclear and appears to depend heavily on how the patent is written rather than any fundamental difference in the underlying technology.

Software flourished in the 1980s and early 1990s before widespread patent protection, demonstrating that copyright law alone effectively safeguards what matters most - the actual written code. This traditional copyright framework successfully prevents direct copying while allowing independent developers to implement similar functionality in their own unique ways.

Software moves much faster than a 20-year cadence and patents inhibit, rather than promote, innovation in that context. Allowing software patents also encourages patent trolls to acquire patents solely to extract settlements through litigation. It’s worth applauding Epic and anyone who fights back against patent trolls, especially in software and healthcare, which helps ensure legal barriers don't stand in the way of innovation.

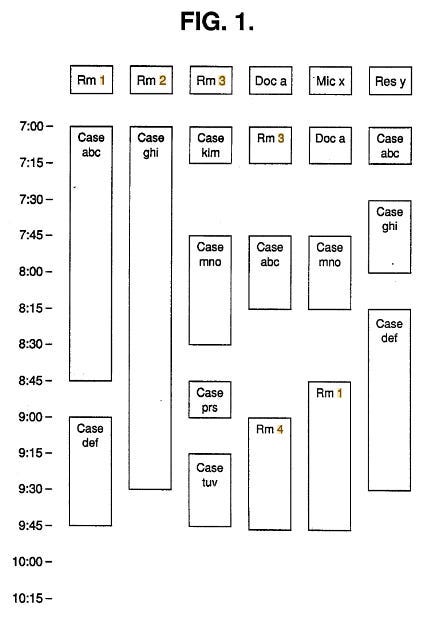

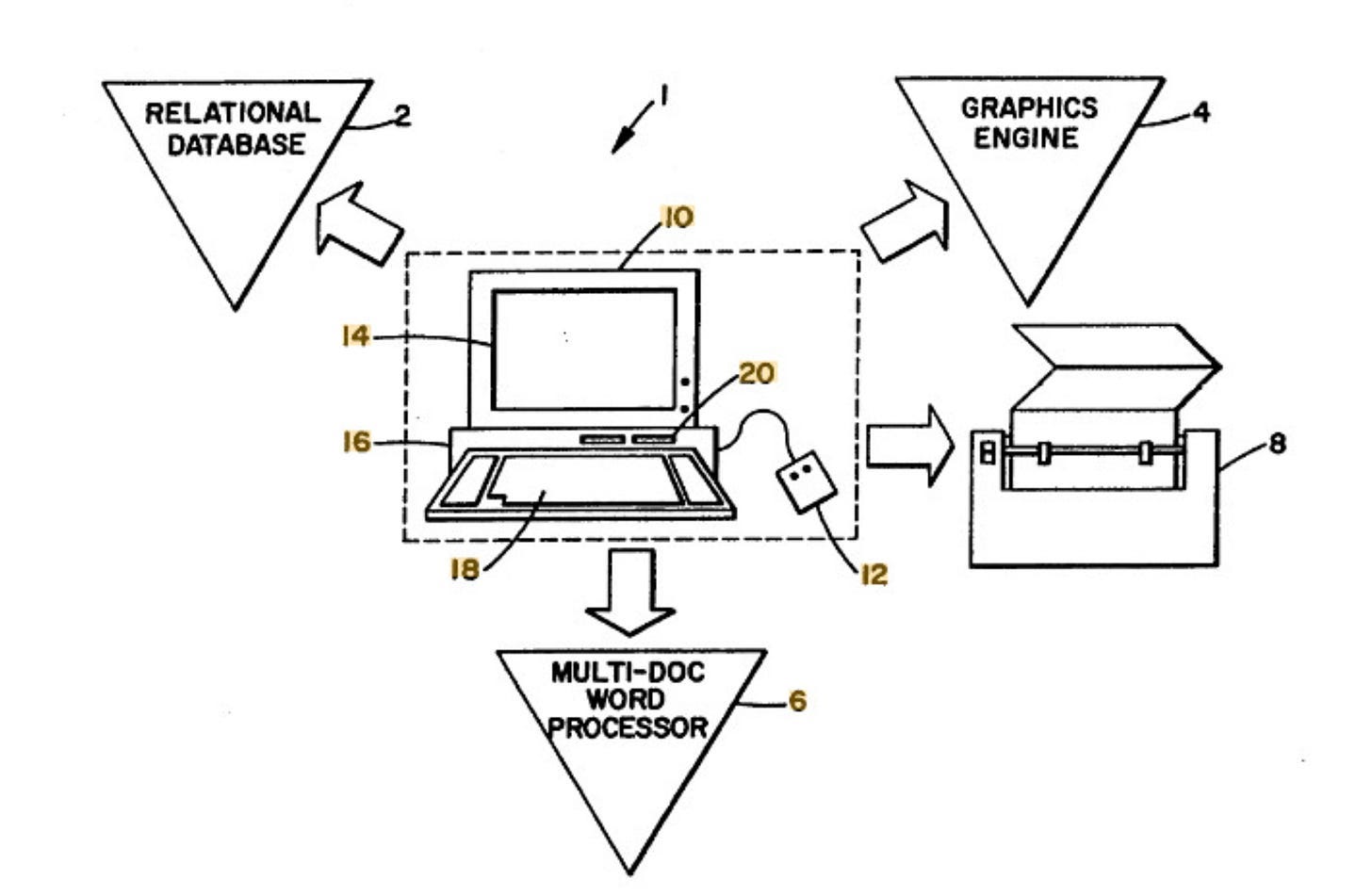

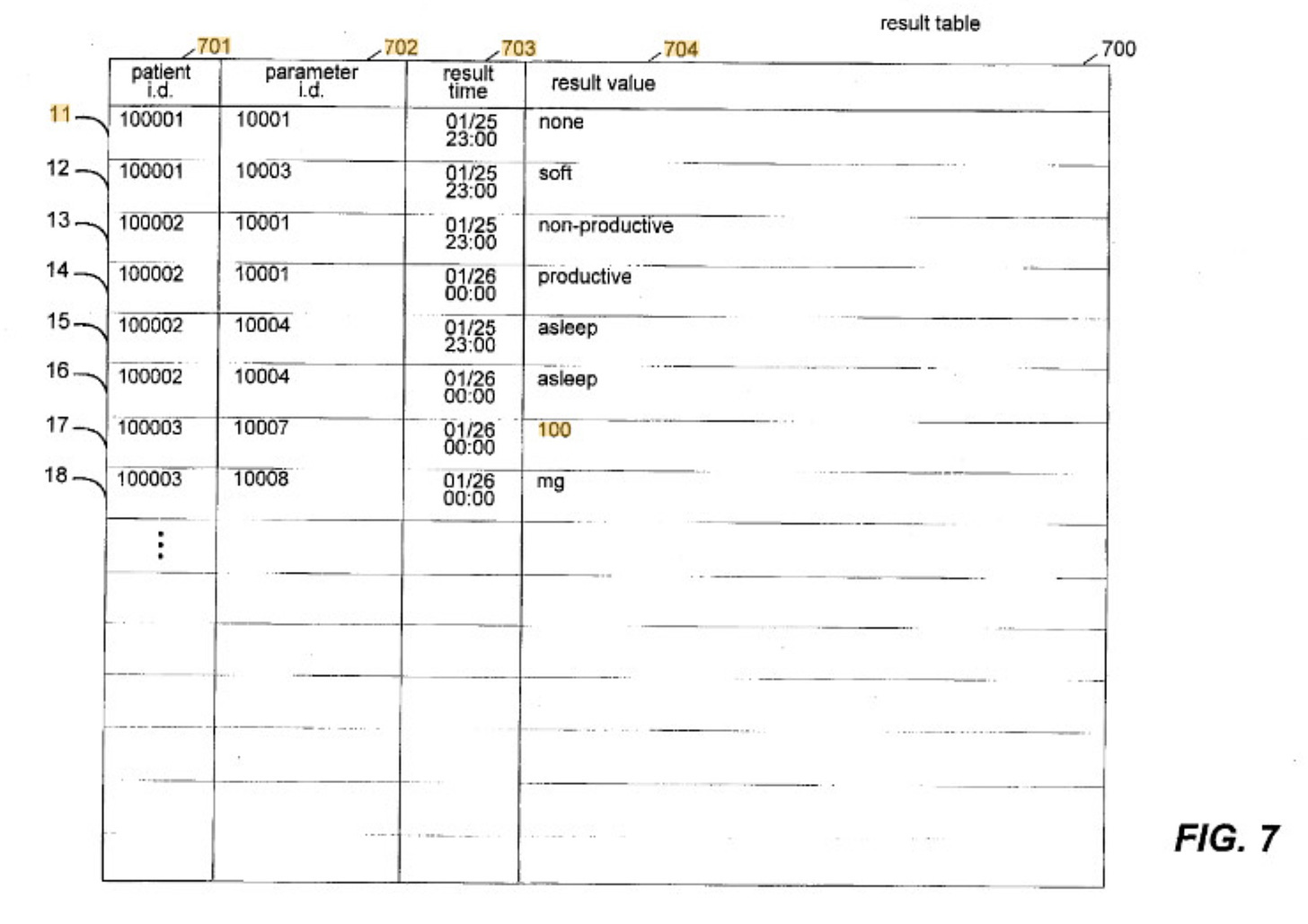

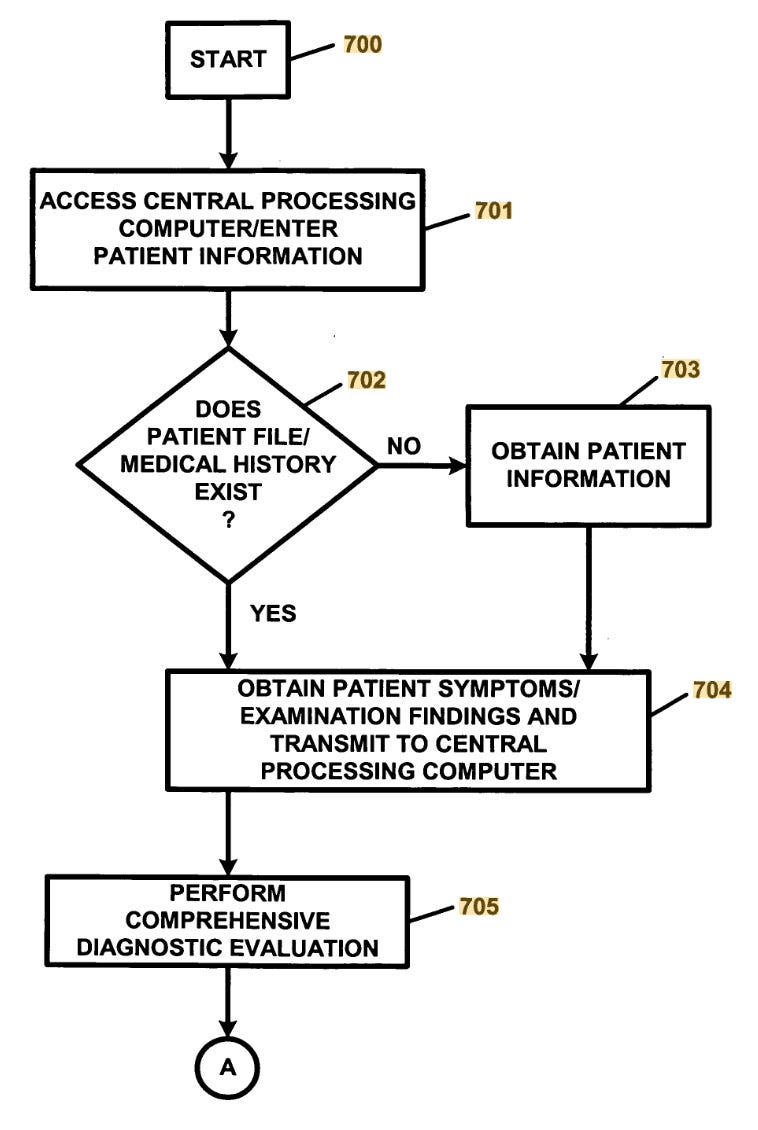

If you’re not convinced simply by this logic, take a quick look at the patents below and consider if granting a vicennial monopoly makes sense for the following capabilities. I’ve included the diagrams for convenience.

Time and time again, Epic has shown that it has no qualms about protecting its IP by fighting any patent claims:

Epic v. Acacia: In 2006, Acacia Research Corporation sued Epic contending that Epic’s Cadence scheduling product infringed on Acacia’s patented “Method and System for Scheduling Monitoring and Dynamically Managing Resources”

Epic countersued that the patent was invalid under 35 U.S.C. §101 (due to being abstract ideas)

McKesson v. Epic Systems: In 2006, McKesson sued Epic contending that Epic’s MyChart patient portal infringed McKesson’s patented “Electronic provider—patient interface system”

In the era before the aforementioned Alice Corp. case, this was a long, bruising, drawn-out case that deposed most of Epic’s senior leadership.

In 2010, the court granted summary judgement for Epic on the grounds that a provider does not initiate communication via MyChart (the patient does), but noted that this loophole could be used by others to circumvent patents. Epic billed McKesson for legal costs ($1,758,009.62).

McKesson appealed, lost, and then appealed to the Supreme Court, who rejected the case, pushing the trial to drag on to 2013.

Ultimately, this case, alongside the more famous Akamai Technologies., Inc. v. Limelight Networks, Inc., ended up being fairly important and fundamentally changed how patents had to be written. Previously, patents could describe processes where different steps were performed by different parties (like a doctor initiating one action and a patient completing another). After these rulings, patent claims had to be written from the perspective of a single actor performing all the steps - a "single actor" approach. This meant patents couldn't claim processes that required multiple independent parties to perform different parts of the method.

Document Generation Corporation v. Allscripts, LLC: In 2008, Document Generation Corporation sued Epic, Allscripts, Cerner, and other dominant (now defunct) EHRs for infringing its patented “Apparatus and method for computer-assisted document generation”

Epic issued counterclaims that the patent was invalid and the case seems to have settled.

Uniloc USA, Inc. et al v. Epic Systems Corporation: Uniloc sued Epic and a number of other EHRs for infringing Uniloc’s patented “Method and system for flexibly organizing, recording, and displaying medical patient care information using fields in a flowsheet.”

The defendants mounted a successful §101 challenge, contending the patent claimed unpatentable abstract ideas rather than specific technical implementations. This legal strategy aligned with the aforementioned Alice framework, which requires patents to add "significantly more" than mere abstract concepts - a test that has since invalidated many software patents that simply computerize conventional business practices.

Preservation Wellness Technologies v. Epic: In 2015, PWT sued Allscripts, Epic and others contending that their patient portals infringed PWT’s patented “System for Maintaining Patient Medical Records for Participating Patient.”

In their defense, Epic and Nextgen challenged the validity of these patents under 35 U.S.C. §101, contending they were unpatentable abstract ideas.

The judge agreed and dismissed all claims

Epic v. Decapolis: In 2022, Decapolis sued multiple Epic customers contending that the use of Epic's software infringed Decapolis’ patented “Apparatus and method for processing and/or for providing healthcare information and/or healthcare-related information” and another similarly titled patent.

24 other entities--including other EHR vendors--entered into settlement agreements with Decapolis.

Epic defended its customers in their cases and countersued Decapolis that Decapolis’ patents were invalid under 35 U.S.C. §101 (due to being abstract ideas).

Epic even continued to sue to extract legal fees from Decapolis.

Epic v. GreatGigz: In 2022, GreatGigz Solutions sued Epic’s customer Christus Health contending that Christus Health’s use of the MyChart patient portal infringed on GreatGigz’s patented “Apparatus and Method for Providing Recruitment Information”, as well as 3 other very similarly titled patents

Epic countersued that the patents were invalid under 35 U.S.C. §101 (due to being abstract ideas)

SynKloud v. Epic: In 2024, SynKloud sued Epic contending that MyChart’s ability to update patients on web and mobile infringed on SynKloud’s patented method of “updating information on one or more of a first party's plurality of communications devices”.

Epic countersued, forcing SynKloud to drop its claims and walk away

What’s interesting is that none of these cases involved Epic taking affirmative legal action against other organizations in regards to Epic’s own patents - the cases were defensive actions. Given Epic’s relatively low number of patents (89 compared to Cerner’s 499) and reliable habit of destroying trolling companies, I wonder if Epic shares my views on software and patents (Judy, if you’re reading this, call me. It would be a fun half-hour discussion).

When it comes to those who question its IP, Epic doesn't settle (at least post-Alice). It also doesn't just win, it destroys - Epic will continue the battle to make the trolls feel pain, if necessary. It’s justified, even a little badass, and shows Epic’s commitment to protecting IP.

Tata and Trade Secrets

While Epic vigorously defends against patent trolls, its protection of intellectual property extends beyond just patents. Perhaps the most dramatic example is Epic's nearly decade-long battle with Tata Consulting over trade secrets - a case that went all the way to the US Supreme Court. As noted in the article:

…Epic claimed that a TCS employee posed as a Kaiser Foundation Hospitals employee to create an account on Epic’s proprietary system while working to help install that software at a Kaiser facility in Portland, Oregon.

The creation of that account then allowed TCS employees in the U.S. and India to download more than 6,000 files to inform the development of the IT company’s competing software, called Med Mantra, Epic alleged.

TCS apparently created a “comparative analysis” spreadsheet comparing Med Mantra with Epic’s software in an attempt to compete in the U.S. EHR systems market, according to the lawsuit.

It is clear that Tata was mining Epic’s Userweb for competitive information. According to Epic’s opening complaint, one TCS employee downloaded over 6,477 documents (1,687 unique files).

This is not the first suit of this variety, but it is the largest, by far. In 2012, Epic sued KS Information Technologies for downloading and copying the “Lesson 1 Welcome to Fundamentals” Ambulatory training from the Epic Userweb in order to offer lessons on the topic. Epic (rightfully) won the case, with an injunction and a payment of $26,568.49.

Similarly, Epic sued Neil Silver in 2013 for making unauthorized copies of a document used in Epic’s "PCB001PC Basics" e-learning and offering training on the topic, winning $18,617.45.

I don’t have as much of a ranting segue for this section as I did about patents, but what’s relevant here is how far and hard Epic is willing to see things through. Tata is a case that went all the way up the court system over a period of 9 years. Epic initially won a $940 million jury verdict, which was subsequently reduced to a mere $140M, which ended with the Supreme Court rejecting Epic’s appeal for a return to higher compensation. Even as late as October 2024, Epic filed a new case against Tata with the Seventh Circuit to argue that the interest owed on that judgment was not paid in full.

The Tata case exemplifies Epic's unwavering commitment to protecting its IP - not just through quick victories, but through prolonged, resource-intensive battles that span years and cross international borders. Even after securing a $140 million judgment, Epic continues to pursue every detail, down to the interest payments, demonstrating that its defense of IP goes far beyond mere legal compliance to fundamental principle.

The Other Epic Supreme Court Case

While we're discussing Epic's legal battles, it would be remiss not to mention Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, arguably Epic's most consequential Supreme Court case - but this one has nothing to do with IP or partnerships. In 2018, in a 5-4 decision authored by Justice Gorsuch, the Supreme Court ruled that employers can enforce arbitration agreements that bar employees from participating in class action lawsuits, finding that the Federal Arbitration Act's policy favoring arbitration trumped the National Labor Relations Act's protection of concerted activity.

The case began when Jacob Lewis, a technical writer at Epic, filed a class action lawsuit alleging Epic had denied overtime pay to him and other technical writers. Epic moved to dismiss, citing the arbitration agreement Lewis had signed requiring individual arbitration of wage-and-hour claims. The case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, where Epic prevailed.

The ruling has had massive implications far beyond Epic or healthcare IT, effectively allowing companies to require employees to waive their right to participate in class action lawsuits as a condition of employment. While this case shows Epic's willingness to pursue litigation to the highest court, its impact on labor rights and access to courts makes it quite different from the defensive IP battles. This case remains one of the past decade's most significant and controversial decisions on employment law.

Screenshot Lockdown

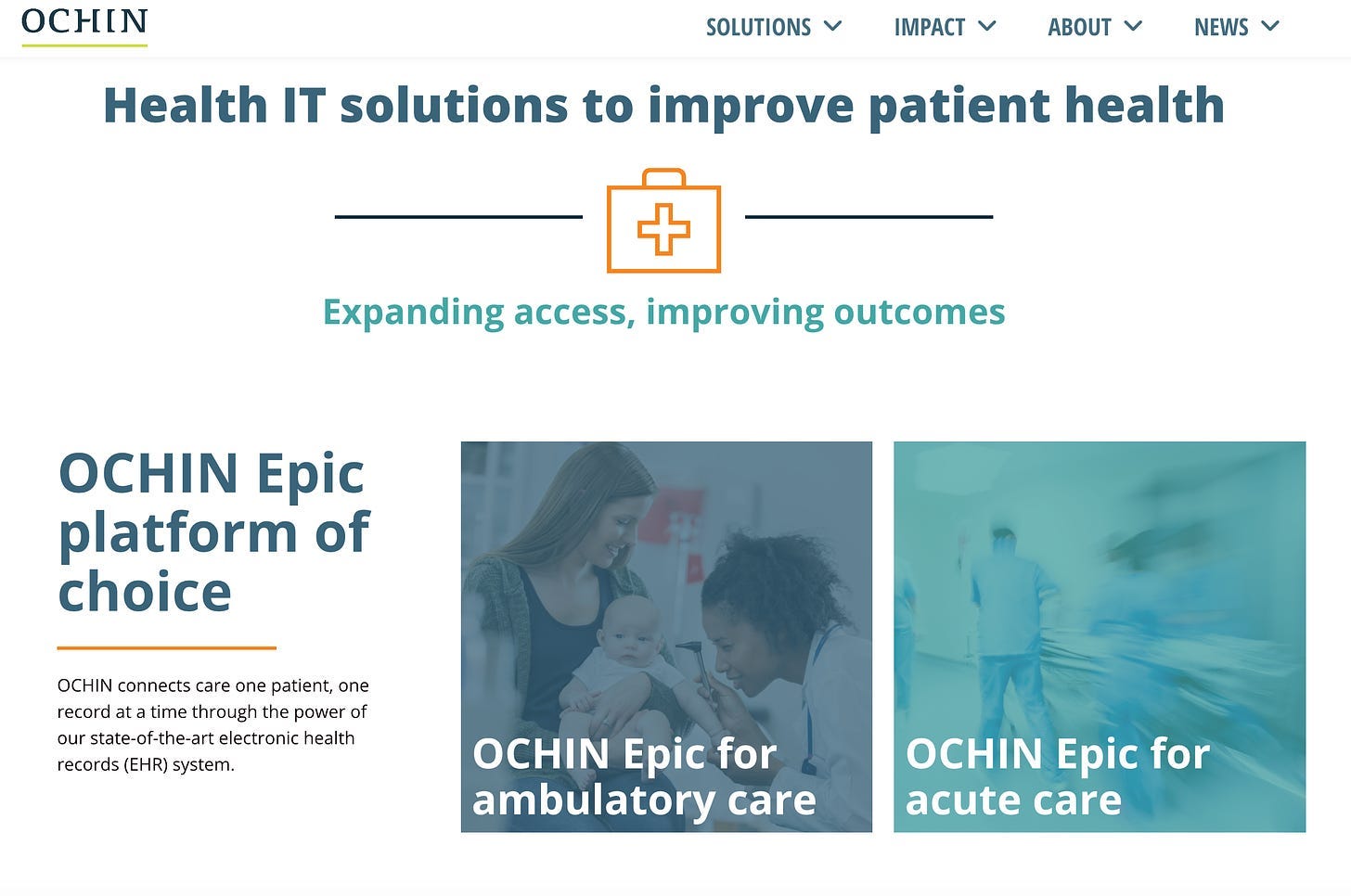

Epic’s actions around the initial ONC Cures Rule are much discussed and oft-maligned. People tend to focus on the letter Epic sent to its customers urging them to push back on certain elements of the Rule. What’s more interesting in this era, though, is not that letter, as neither CNBC nor any other media outlet actually published the full content, so it’s really hard to judge beyond the high-level optics.

Rather, Epic’s full comment on the proposed rule a year prior prominently displays how it thinks about the world. This document is 88 pages of fun, and the most pertinent section is Epic’s summary of its views on intellectual property:

Honestly, even as a former employee, this is where Epic loses me a bit.

As a developer, it’s reasonable to want to protect the graphical elements of your software. As mentioned earlier, I’m personally not a fan of patents for software, but certainly, there’s ample room in US law today to protect user interfaces (via Alice Corp). Furthermore, many creative expressions in the UI are copyrightable.

Trying to prevent the screenshot and recording exchange (or really any digital media) is roughly the equivalent of holding sand in your hands - the tighter you squeeze, the more it slips through your fingers.

It’s also a footgun policy for Epic that hurts them more than it helps. Trying to prevent screenshots through contractual terms or other means hinders legitimate discourse about software, making it harder to educate users, impeding technical discussion and improvement, and, ultimately, not really adding any meaningful protection beyond existing IP rights.

Luckily, the ONC Cures Final Rule effectively ended this practice (pursuant to fair use copyright rules) by making it clear that preventing screenshot sharing through contractual terms or other means violates certification requirements for EHRs. Epic accordingly updated their policies to respect this law, as well as the ONC Communications Rule. This historic pattern reveals Epic's extraordinarily careful protection of IP, though.

Partnerships (or lack thereof)

Epic's fierce defense of intellectual property is just one piece of a larger puzzle. To understand Epic’s resistance to platformization, we need to examine Epic's formative experiences with partnerships, starting with one ambitious experiment in the early 2000s.

The Dutch Experiment

Historically, there was no idea of an external vendor partnership with Epic. The backstory there is a segue, but one worth telling. In the early 2000s, when it was a hungry upstart, Epic had negotiated and kicked off a partnership with Philips, a dominant player on the hardware side of the health system equation. It was a well-intentioned partnership full of synergies - Philips' large customer bases in medical imaging and monitoring solutions would help Epic scale, while Epic would offer Philips a way to expand as a software vendor. The details of the partnership, in retrospect, read like an alternate reality:

As part of the Epic-Philips alliance, Epic will produce the core RIS that will drive both Epic's Radiant and Philip's Vequion-branded radiology information systems. This core RIS will support integration with Philips' modalities and PACS. It will also provide support for industry-standard interfaces with other vendors' PACS and modalities.

From a year later:

The collaboration led to the development of a software engine that drives both Epic's and Philips' radiology information systems. Philips also rebranded Epic's healthcare IT systems under the product name Xtenity Enterprise, a portfolio of modules and applications such as billing; admissions, discharge, and transfer; and inpatient pharmacy. Smits expects few changes in regard to Epic if the deal with Stentor closes.

Unfathomable today, the partnership drove deep collaboration, pushing Epic to open its first international office in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, a short train ride from Philips’ Eindhoven headquarters.

Something that is underrated and oft-forgotten: co-development is the ultimate challenge in partnership land, with extremely high investment of time and resources from both parties. But investment alone isn't enough - the deeper the scope and loftier the vision, the more that raw determination to just persevere and see things through cycles of progress and setbacks is critical. Few companies have that intestinal fortitude, especially public ones exposed to the violent oscillations of the public markets and shareholder scrutiny.

Co-developing EHR software requires a deep scope and lofty vision, and predictably didn’t last. While Xtenity launched in 2005 with some mid-market traction, the partnership ended in 2006:

Philips Medical Systems and Madison, Wis.-based Epic Systems Corp. have made the decision to end their collaborative partnership towards developing the Xtenity Enterprise system. The two companies will no longer develop or offer the system, which is a suite of enterprise and departmental healthcare information systems targeted at mid-sized hospitals.

This was scarring for Epic, left with wasted effort and the baggage of failure. With commitments to its first international customers (in the Netherlands) secured, Epic decided to move forward on its own.

This seminal event influenced Epic’s partnership strategy (none at all) for almost two decades. When external applications or vendors wanted to engage Epic, the path was mediated by a mutual customer, leading to the process pictured below. Applications were (and still are) free to connect using the many standards-based interfaces and APIs that Epic had developed, but building a direct relationship with Epic was nigh impossible.

The NOVO Health Debacle

The recent Epic v. Focus Systems litigation offers a fascinating window into Epic's approach to partnerships and IP protection. While the public narrative around Epic often focuses on its reluctance to partner with external vendors, the Focus Systems situation reveals deeper complexities in how Epic approaches these relationships.

The Initial Pitch

In 2019, NOVO Health approached Epic with what seemed like a promising proposition. Led by CEO Curt Kubiak, NOVO Health presented itself as an established business providing direct-to-employer bundled payment programs, connecting employers with independent healthcare providers for cost-effective services. NOVO Health’s pitch was straightforward: supplement its existing offerings by extending Epic's software to its bundled payment partners through Community Connect, a program that allows smaller practices to partner with a larger “host” hospital that uses Epic. In this model, a larger hospital essentially manages Epic and extends its instance to the partner providers, allowing smaller organizations to leverage Epic’s benefits without the complexities of hosting.

NOVO Health appeared to have all the necessary pieces for success:

NOVO Health claimed to have over 160 established contractual relationships with healthcare providers;

It positioned itself as a successful business that "didn't need Epic to make money;" and

The model seemed to align with Epic's Community Connect program principles.

The group entered into a license agreement with Epic in July 2020 and went live hosted on Microsoft Azure in October 2021.

Early Red Flags and Hidden Agendas

However, NOVO Health was also collaborating with Bruce Schaumberg, who had previously approached Epic directly about becoming a reseller (which Epic declined). Through various corporate entities including Focus Systems and Focus Solutions, Schaumberg allegedly positioned himself to leverage the NOVO Health relationship to gain insider access to Epic's software and documentation.

Some concerning elements emerged in late 2021 and early 2022:

NOVO Health created a subsidiary (NOVO Health Technology Group or NHTG) to hold the license agreement;

The company's financials were significantly worse than represented;

NOVO Health formed a secret "Collaboration Agreement" with Schaumberg's Focus Systems aimed at reselling Epic's software; and

It began targeting healthcare providers who had no prior NOVO Health relationship, specifically marketing access to Epic.

NHTG stopped paying Epic in 2021, just prior to their initial go-live;

The Unraveling

As Epic states in its opening brief, “things did not go well”. The implementation quickly ran into problems in 2022 and into 2023:

User satisfaction surveys consistently showed poor results (4-6 out of 10) as part of Epic’s Community Connect Accreditation program;

Support tickets went unaddressed;

Customers reported threats and harassment; and

Multiple healthcare providers began terminating their relationships.

NHTG owed Epic over $$7.3 million in unpaid fees;

Arguments turned into litigation in 2024. NOVO Health started bankruptcy proceedings in order to keep its Epic license, which was dismissed. However, Epic responded by countersuing Schaumberg and one of his secondary companies for theft of trade secrets. The countersuit culminated in a voluntary dismissal by Epic in September 2024, likely due to a settlement out of court.

The NOVO Health saga ultimately shows that while Community Connect does allow Epic to extend its reach to smaller community-oriented providers, Epic draws the line when the operating partner is a software vendor and not a provider. Furthermore, Epic does not want organizations to profit from reselling its software, pushing them to attract new Community Connect partners through non-software value propositions.

Really no resellers?

What’s fascinating is that some Epic customers appear to exist in the grey zone, offering Community Connect access despite not being provider organizations themselves. For instance, OCHIN (Oregon Community Health Information Network) is a nonprofit healthcare innovation center headquartered in Portland, Oregon. Founded in 2000, OCHIN provides health information technology services, including Electronic Health Record (EHR) solutions via Epic, research and analytics services, support for community health centers and safety net clinics, and health data exchange solutions. OCHIN also markets its Epic instance online:

Likewise, Acumen even more directly markets its nephrology-optimized instance of Epic as part of its value proposition:

It’s worth noting that both OCHIN and Acumen are in many ways somewhat different from NOVO:

OCHIN manages one of the largest community health center networks in the United States with the noble mission of serving safety-net healthcare providers and underserved populations.

Acumen is now part of Interwell, a large value-based kidney care provider formed from the merger of Fresenius Health Partners, the value-based care division of Fresenius Medical Care North America, with Cricket Health and InterWell Health

All this to say: the reseller line is blurry, as OCHIN is a technology services organization, while Acumen was (prior to the merger) a technology division of Fresenius Medical Care North America.

One has to wonder whether the experiences of these unique Community Connect implementations that lacked a central “hub” provider organization influenced their current “no reseller” policy seen with NOVO.

Through Philips and NOVO, we see how a fear of partnership still might have been instilled culturally in Epic - Epic iterates over and over in the brief how its chief desire is to ensure health system customers are happy. External partnerships are uncontrollable dependencies and risks to that end, a lesson it learned early from Philips and again more recently with NOVO.

The First Battle

While the Philips and NOVO stories illustrate Epic's evolving stance on partnerships, perhaps the most formative partnership-adjacent experience came much earlier. Before Epic grew into the dominant force it is today, a different kind of partnership - one between former employees and their new employer - nearly derailed everything. This early brush with existential threat would prove instrumental in shaping Epic's future approach to both partnerships and IP protection.

The IDX Story

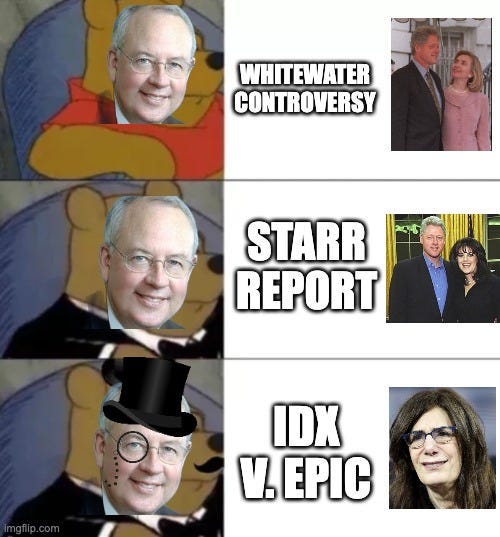

In 2001, IDX Systems (rebranded to Virence Health under GE and now athenaIDX/athenaFlow/athenaPractice under athenahealth) sued Epic Systems. Led by Ken Starr of Clinton-Lewinsky fame, IDX alleged Epic had conspired with two former IDX employees, Mitchell Quade and Michael Rosencrance, after they joined University of Wisconsin Medical Foundation. The lawsuit claimed the individuals breached their respective NDAs by sharing IDX's trade secrets with Epic and preventing IDX from winning the UWMF contract.

At first, decisions were strongly in Epic’s favor. The district court dismissed all claims. It held that the plaintiff had failed to state a valid trade secret claim since it did not plead the claim with sufficient specificity, submitting multiple user manuals that simply detailed their EHR’s functionality. This fumble is somewhat surprising given the caliber of IDX’s counsel but perhaps speaks to how novel and nascent private action on software trade secrets was at the time. The court also dismissed the breach of contract claim since:

It was preempted by the Wisconsin Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA); and

The NDA was invalid because it lacked temporal or geographic limitations.

However, IDX appealed. While the Seventh Circuit Court upheld the district court's ruling on the trade secret claim, the Court reversed the preemption and contractual claims. The Court ruled that non-disclosure agreements could protect information beyond just trade secrets, and unlike non-compete agreements, NDAs didn't require geographic or temporal limitations since "knowledge does not respect borders." This ruling notably strengthened businesses' ability to protect their confidential information through NDAs, even when that information didn't meet the strict definition of a trade secret under the Uniform Trade Secrets Act. Epic and IDX settled after the appellate ruling.

Epic was a much smaller upstart at the time - with around 850 employees and $105 million in revenue compared to IDX’s $500+ million. Today, Epic has ~14,000 employees and $4.9 billion in revenue. Epic was up against a better resourced competitor with one of the most prominent and polarizing legal figures of the 1990s leading the lawsuit. Having the majority of its leadership deposed must have been jarring. If Epic had been found liable, the monetary damages could have been high, including actual losses suffered by IDX, any unjust enrichment Epic gained from the act, and also up to treble damages for willful and malicious misappropriation. This outcome would have been disruptive operationally, possibly requiring code changes or even outright avoidance of certain feature sets deemed part of IDX’s trade secrets.

Those things did not come to pass, though. Epic survived this ordeal via the settlement and went on to sign Kaiser Permanente a few years later, slingshotting them into the upper echelon of EHRs and onto the trajectory leading them to its dominant position today.

Organizational culture is more a function of the collective aggregation of highs and lows throughout the years than the distillation of any one leader’s personality or values chosen for a company website. Looking at the full corpus of actions and behaviors in this article and reading the tea leaves, you have to wonder if this particular event put the fear of God into Epic, nudging it on the path of intellectual property protectionism and wariness of external parties. It certainly seems like Epic stood briefly on the precipice, wondering whether one mistake might submarine its whole mission.

Conclusion

We circle back to where we started. To paraphrase Dennis Green, Epic is who we thought they were - an organization that has not leaned into a full platform approach, who historically has chosen to build rather than partner, and who will ardently defend their intellectual property. After nearly 5000 words and a variety of stories, we see how some of the why may be different than what we expect, rooted in traumas and tribulations incurred through the act of building, singularly focused on ensuring their provider customers were successful.

The stories we've explored – from the failed Philips partnership to the bruising battles with patent trolls, from the Tata litigation to the IDX crucible – paint a picture not just of what Epic does, but why they do it. Epic’s seeming insularity isn't merely corporate stubbornness or NIH syndrome, but rather the product of hard-won lessons about the costs of dependency and the value of self-reliance. Its fierce protection of intellectual property isn't simple possessiveness, but a reflection of existential threats weathered and overcome.

Yet there's an irony here. The very experiences that drove Epic to build walls may have also cemented its foundation for success. Early trauma with partnerships pushed Epic toward self-sufficiency, leading to the comprehensive integrated system that became its hallmark. Zealous IP protection, born from defensive necessity, helped create the moat that preserves its market position today. The scars of Epic’s battles became the source of its strength.

As Epic continues to evolve and the healthcare technology landscape shifts beneath it, these historical patterns offer both context and caution. The defensive postures that served Epic well in the past likely needs to adapt to a future that increasingly demands interconnection and collaboration. The triple threat of information blocking, antitrust, and the simple pressures of a changing industry under duress will test them in new ways. But understanding the deep-rooted reasons behind its approach – reasons written in the scar tissue of failed partnerships and costly litigation – helps explain why such evolution, as it comes with programs like Vendor Services and Workshop, is careful and considered rather than swift and sweeping.

In the next article, we’ll (finally) examine these programs more deeply as part of a fuller look at the ways to connect, integrate, interoperate, and partner with Epic. In the meantime, perhaps we can appreciate that even their most frustrating qualities – their wariness of partnerships, their fierce protection of IP, their careful evolution – perhaps aren't just arbitrary choices, but battle scars earned the hard way. Sometimes understanding the "why" behind the "what" doesn't change the reality, but it does help make sense of it.

A big thanks to all that contributed or reviewed this piece: Jonathan Hutton, Nick Nunez, and Matt Fisher

¹ This article on Epic’s history is for informational purposes only. The author has no official relationship with or endorsement from Epic Systems Corporation. All trademarks, service marks, and trade names referenced in this presentation are the property of their respective owners. The information provided here is based on publicly available resources and does not represent official guidance from Epic Systems Corporation. Please refer to their website and contact their representatives for the most up-to-date guidance.

² It should be obvious, but I am not a lawyer. The above represents my understanding of intellectual property law as it applies to software based on publicly available sources, my experience in the industry, and my opinions/hot takes on how we could improve things. Nothing in this discussion should be construed as legal advice, and you should consult qualified legal counsel for specific guidance on these matters.

I’m still working through but wanted to call out the interesting point you make about software’s likeness to writing. I never thought about it in this way.

Great stuff Brendan! I don't know how you do it but so glad that you do!