Any build/buy decision is hard, especially in enterprise software. Divining the differences between electronic health records, though, is hard mode. Luckily, we live in the era of great content and tools that our forefathers did not and Elion exists to provide the intelligence you need.

If you’re a tech-enabled practice building/buying an EHR or a software company considering EHR certification, come chat with us at HTD Health, my new employer, for a trusted partner to plan, design, and develop along your journey.

“Do I need a certified EHR?”

One of the most common and foundational decisions in digital health, it’s oft-discussed and written. With the fuel of the pandemic leading to a massive rise in virtual and hybrid care practices, the off-spring of the first generation of Teladocs, Livongos, and Doctor on Demands, the question has only intensified. Several have written about adjacent topics:

“To E(HR) or not to E(HR)” tackled it from the pure perspective of the relative challenges of building or buying.

“The Digital Health Provider’s Guide to Selecting an EHR” went deeper into the principles of EHR selection

“Headless EHRs” detailed the murky space between build and buy, separating FHIR-based application development platforms and decoupled EHRs as sub-categories of headless EHRs

While the road to choosing a path has become much more clear, the root question has been of handwavy explanations and quick references to dense regulatory literature:

Thus, the baseline assumption among prospective EHR users who will be seeing patients who are covered by government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid is that they need one that is “ONC certified. In the EHR build/buy decision, this looming, poorly defined specter is one of the two main drivers that can shift a potential EHR builder to become an EHR buyer.

But if you ask people what “ONC certified” actually means or when it’s truly required, you’ll likely get a blank stare. And for good reason - it turns out that the answer is quite complicated. And shockingly, the statement that “most providers need to use a certified EHR” is perhaps not necessarily true.

We’re truly sorry about that and we’re here to do better.

Let’s right that wrong and finally answer “Do I need a certified EHR”, journeying into the maze a la young Jennifer Connelly and David Bowie in Jim Henson’s (somehow hit) movie Labyrinth. We’ve dug through the regulations and government websites so you don’t have to. By the end of this, you should have a solid understanding of what “ONC certified” means, and, more importantly, what you need to be looking for as you evaluate EHRs.

What does “ONC certification” mean?

In a vacuum, an electronic health record can mean a heck of a lot of different things. “Vertical SaaS but for doctors” cannot possibly do justice to the variety and variation that medicine demands. Just as we divide the animal kingdom all the way down to genus and species, so too can the roles and responsibilities of practitioners and administrative staff in healthcare be fractally divided. Doctors, nurses, schedulers, registrars, revenue cycle managers, and so much more, all packed into a single piece of software? On top of that, you layer in two drastically different domains with barely related workflows between inpatient and outpatient and sprinkle in a variety of specialties that do completely dissimilar things.

Brief Background and History

A large amount of complexity in regards to EHR certification is simply that the internet is cluttered with the exhaust of its 15 years across 3 different administrations. There are countless pages on Meaningful Use, MIPS, MACRA, Cures, and a variety of the sub-components the ONC and CMS have named, renamed, and stitched together. For a deeper dive into regulatory history, this series explains Meaningful Use, Cures, and other regulations in more detail, but for our purposes:

Meaningful Use Initial Stages (2011-2017):

The Meaningful Use program was rolled out in three stages.

Stage 1 (2011-2012) focused on data capture and sharing.

Stage 2 (2014-2015) emphasized advanced clinical processes.

Stage 3 (2017 onwards) targeted improved outcomes, requiring more comprehensive data sharing and patient engagement. The final rule for this was passed in 2015, so it was integrated/implemented through MIPS/MACRA below.

MACRA and the Quality Payment Program (2015):

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015 introduced the Quality Payment Program (QPP).

Under QPP, eligible clinicians could participate in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) or Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

Meaningful Use for Medicare providers transitioned into the Advancing Care Information (ACI) performance category within MIPS.

The Medicaid EHR Incentive Program continued independently for Medicaid providers.

Promoting Interoperability (2018-2021):

In 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) rebranded ACI to Promoting Interoperability (PI) to emphasize interoperability and the exchange of health information.

The PI program streamlined measures, reduced reporting burdens, and focused on key areas like e-prescribing, patient access to health information, and public health data exchange.

Changes in 2021:

By 2021, the focus on interoperability became more pronounced, aligning with broader goals like patient-centered care and data access.

The Medicaid portion of Promoting Interoperability was sunset.

The 21st Century Cures Act, which complements the Promoting Interoperability program, mandates the use of APIs to improve data exchange and prevent information blocking, further enhancing interoperability efforts.

The ONC’s Base EHR

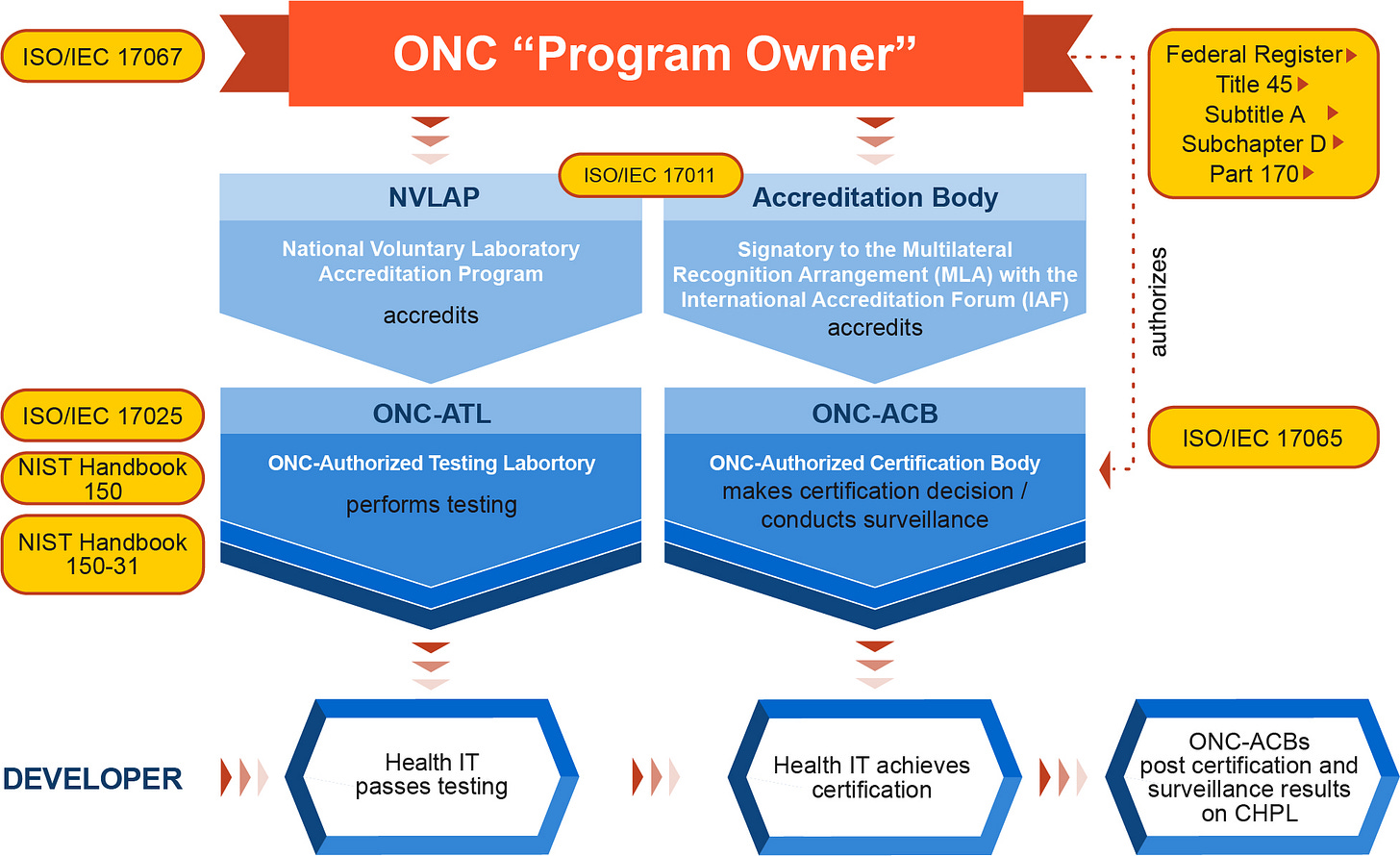

While an EHR can mean a lot of things, a certified EHR is far more concrete, as certification is a function of the Office of the National Coordinator's regulatory powers. The ONC Health IT Certification Program (link) was launched in 2010. The voluntary program was established by ONC to provide for health IT certification and to support its availability for encouraged and required use under other federal, state, and private programs.

Said more plainly - the ONC is responsible for maintaining the definition of an EHR from a US government perspective. It sets a minimum bar for an electronic health record's functionalities and features. Within the ONC Health IT Certification Program, these functional requirements are known as “certification criteria.” By demonstrating conformance against these certification criteria (sometimes while relying upon other sub-vendors), developers can have their software certified as Certified Health IT.

Notably, the ONC themselves do not do the certification or directly review software (aside from rare cases) but instead have various private companies who are authorized to perform the testing (ONC-Authorized Testing Laboratories or ONC ATLs) and certification (ONC-Authorized Certification Bodies or ONC-ACB). Today, there are just three remaining companies offering this:

Looking at the data available in theCertified Health IT Product List (a cool tool the ONC makes available publicly for anyone to understand what EHRs and health IT are certified), we can see clearly that Drummond is the clear winner in terms of testing and certification:

“Hold up a second,” you may be saying, “Does Certified Health IT equate to a certified EHR?” If only it were that simple and easy. To allow for more best-of-breed, choose-your-own-adventure selection of EHR capabilities, the ONC moved towards a modular approach, where a provider could choose a variety of certified Health IT. Software certified as Certified Health IT is a superset of any application product that is certified to one or more criteria. That does not make them an EHR - it is possible to only certify to a single criteria, be certified Health IT, but not be a full EHR. Similarly, there are more "certification criteria" than those that actually comprise the various definitions of certified EHRs, as some criteria are relics of shuttered programs that are still tracked and other criteria are future-facing, signaling the ONC’s intent to potentially include them in their EHR definition in the future.

While empowering in terms of removing the necessity of monolithic software, the reality is that most traditional providers still use a single EHR that meets all criteria directly (or partnered with another certified vendor under the hood).

If you’re interested in going deeper into the ONC Health IT Certification Program, there’s plenty to explore:

This helpful document runs through all aspects of the program, including things that are fun but not in the scope of this article like the Standards Version Advancement Process and certification bans.

The Certified Health IT Product List (CHPL) is a powerful tool for all interested in EHRs, especially if you are trying to understand an EHR’s FHIR capabilities.

Separate from the individual criteria or the designation of certified health IT, the ONC maintains their “Base EHR” definition (regulatory text version here):

This begs the question - “how many of the certified products are full Base EHRs?” Props to the ONC again for CHPL - it really is a great data tool, with the “big 3” of modalities: an easy-to-use UI, a JSON API, and a bulk export. Exporting all of CHPL’s active products and filtering by the Base EHR criteria, we see that only 173 out of 696 active products across 138 vendors fully fulfill the criteria for Base EHR.

Notably, some of the largest EHRs, like Cerner, don’t have a single product that is a full Base EHR. Instead, they’ve splintered their EHR into multiple smaller modules, likely to make recertification more contained and modular:

The CMS’ Certified EHR Definition

Okay, we’ve established a federal agency's definition of an EHR. That must be what I, a digital health provider, need to use, or the ONC will come after me, right?

The labyrinth does not stop there, friends. While the ONC provides this core definition and a well-structured certification program for health technology developers, its regulatory authority does not lend itself to enforcement, encouragement, or requirements regarding what providers must do, at least regarding certified EHRs.

Instead, another federal agency, the CMS, has been the primary driver of adoption through a variety of programs since the initial Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. In that initial model, while CMS established the criteria for meaningful use and managed the incentive payments, ONC specified the technical capabilities required for EHR systems to support meaningful use objectives.

Steven Posnack, Deputy National Coordinator of the ONC, has some nice historical perspective on the evolution:

As the nation’s largest payer, the CMS has financial levers to ensure providers are using EHRs and embracing new technologies. This is structured today through two main CMS programs:

Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program – Medicare-eligible hospitals and critical access hospitals must use Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) to avoid downward payment adjustments from Medicare.

Quality Payment Program (QPP) – Medicare-eligible clinicians participating in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) must use CEHRT to receive full points in the Promoting Interoperability category, which ultimately impacts the payments you receive from CMS.

Clinicians who participate in Alternative Payment Models (APMs) are similarly required to use CEHRT. However, the each alternative payment model can have their own definition of CEHRT in order to pull in the criteria that program deems necessary for success.

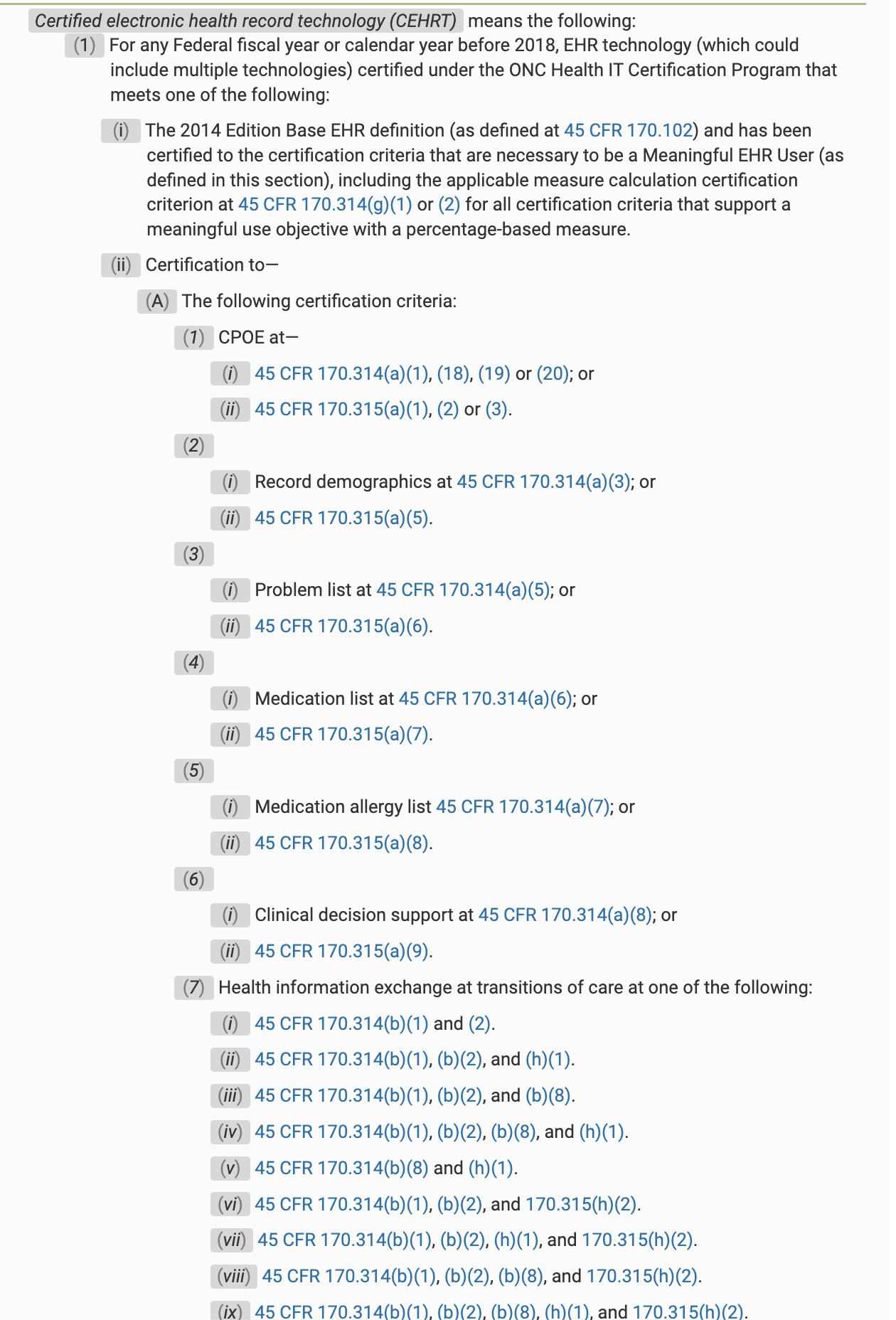

It is the CMS that defines a certified EHR, which has evolved over the past two decades. This definition began during Meaningful Use and was listed in42 CFR 495 (the regulatory text surrounding the Electronic Health Record Incentive Program). Before 2019, they spelled out a laundry list of specific criteria:

However, that definition shifted in 2019:

The CMS copies this definition into MIPS here, with one addition: any providers participating in Alternative Payment Models have a slightly different definition of CEHRT, where the specific APM can dictate what additional criteria beyond ONC’s Base EHR definition are needed for that payment model:

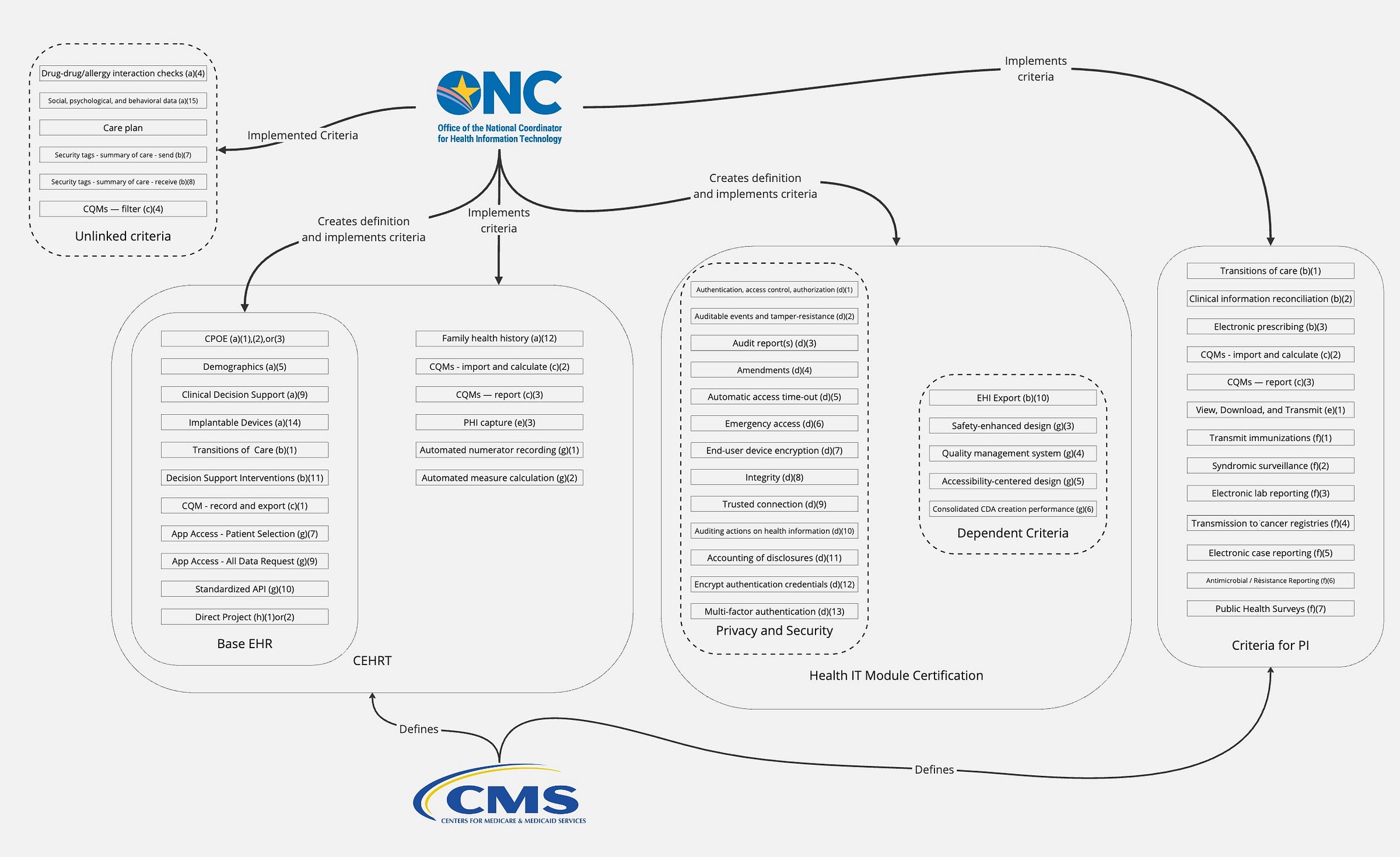

To summarize, our result, then, is that there are technically four definitions of an EHR by the government:

Base EHR

The ONC’s definition of certification criteria that forms the lower bound and is often included in other definitions

Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) for Medicare Promoting Interoperability

The CMS’ definition in 42 CFR § 495

This is currently ONC’s Base EHR as well as family health history, PHI capture, measure calculation, and CQM functionality

Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) for QPP MIPS

The same as “CEHRT” for Medicare P, but redefined in 42 C.F.R. § 414.1305

This is currently ONC’s Base EHR as well as family health history, PHI capture, measure calculation, and CQM functionality

Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) for QPP APM

The CMS’ definition in 42 C.F.R. § 414.1305

The ONC’s Base EHR and any additional criteria defined in the specific APM

Of the 173 products that were full Base EHRs, only 133 are fully certified EHRs across 104 vendors by the MIPS and Medicare Promoting Interoperability definition.

Promoting Interoperability Criteria

Folks, this may surprise you, but we're not done yet. The road is long and winding, filled with twists, turns, acronyms, and compounding regulatory references. In addition to the criteria that make up a certified EHR, the CMS specifically requires additional capabilities to fulfill measures in the Medicare Promoting Interoperability program (inpatient) and Promoting Interoperability requirements for MIPS reporting (outpatient).

The Medicare Promoting Interoperability program has four main objectives, with measures that change and evolve each year as the CMS adds, removes, or updates them. For 2024, here are the objectives and measures:

These measures are often (but not always) tied to ONC-certified criteria. This linkage is enumerated helpfully by the CMS in the ZIP file here, referencing these criteria:

Transmission to public health agencies — syndromic surveillance

Transmission to public health agencies — reportable laboratory tests and value/results

Transmission to public health agencies — electronic case reporting

Transmission to public health agencies — antimicrobial use and resistance reporting

Transmission to public health agencies — health care surveys (optional)

Noticeably missing from the list is criteria (f)(4) Transmission to cancer registries. This is because, despite nearly identical naming, the criteria required in MIPS Promoting Interoperability diverges from Medicare Promoting Interoperability slightly, subtracting the antimicrobial reporting andadding cancer reporting as an option to Public Health Registry reporting:

Overall, the mandatory criteria set is lighter for MIPS Promoting Interoperability, with fewer required public health and clinical data exchange measures. Syndromic surveillance is optional and Electronic Lab Reporting is omitted altogether for MIPS:

Transmission to public health agencies — electronic case reporting

Transmission to public health agencies — syndromic surveillance (optional)

Transmission to public health agencies — antimicrobial use and resistance reporting (optional)

Transmission to public health agencies — health care surveys (optional)

When factoring in the Promoting Interoperability measures, only 57 products of the 137 certified EHRs include all necessary criteria, showing that most expect their customers to use other certified products they or partners make alongside the core EHR functionality.

Health IT Module Certification

Looking at the full list of certification criteria maintained by the ONC and filtering out anything included in the three EHR definitions or needed for Promoting Interoperability, we still have 24 certification criteria defined by the ONC that seemingly have no home.

Digging in, certain criteria are dependencies or prerequisites in the ONC’s certified health IT program. Most of these are related to safety, quality, and accessibility, which makes sense. If the government is going to sanction your software with a certification, they want it to not only do certain functionalities, but perform them safely and securely. For example, the “Health IT Module dependent criteria” that the ONC has defined in 45 CFR § 170.550(g) kick in as soon as you try to certify any other criteria:

Similarly, the ONC has a “Privacy and security certification framework” in 45 CFR § 170.550(h) that activates when certifying different criteria. If pursuing base EHR / CEHRT, these all get pulled in:

Remaining Criteria

This leaves a small grab bag of criteria, which aren’t actively tied to any CMS program or ONC certification step due to varying reasons. Again, shout out to Kyle Meadors for his help here.

Included in the certified EHR definition for a MIPS APM that is finished (CPC+)

Mentioned in the HTI-1 proposed rule, but dropped

Previously in Meaningful Use, now just hanging out

Previously in CEHRT, now hanging out

Untethered from the ONC’s base EHR definition, any CMS reimbursement program, or the ONC’s criteria for certification, these are truly optional at this point.

Summary

Summing it all up, it looks a little something like this:

The ONC:

Defines what criteria make up a Base EHR

Defines what criteria are required for Health IT Module Certification

Implements all criteria needed by their definitions or the CMS’ definitions

The CMS:

Defines what criteria make up Certified Electronic Health Record Technology via:

Medicare Promoting Interoperability definition

QPP MIPS Promoting Interoperability definition

Each QPP Alternative Payment Model definition

Defines Promoting Interoperability measures that require specific criteria

If I'm an inpatient provider organization, I'm certifying my EHR/Software against the criteria specified in the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program administered by CMS.

If I’m an outpatient provider organization, I am assessing the criteria in the MIPS Promoting Interoperability program or the QPP Promoting Interoperability program specific to my Alternative Payment Model.

The totally-predictable-in-hindsight reality is that ONC certification is complex, with different definitions of EHR depending on the CMS program and a fair amount of optionality across criteria depending on the provider type. This complexity is tracked in the spreadsheet here:

It’s worth noting that these definitions and criteria will only continue to change. The ONC’s iteration is ongoing, with HTI-1, HTI-2, and other future rules further adding, removing, and updating criteria. In particular, the predictions by John Travis here seem spot on - we can expect criteria related to prior authorization, for sure, but also perhaps CDS Hooks or other advanced FHIR capabilities.

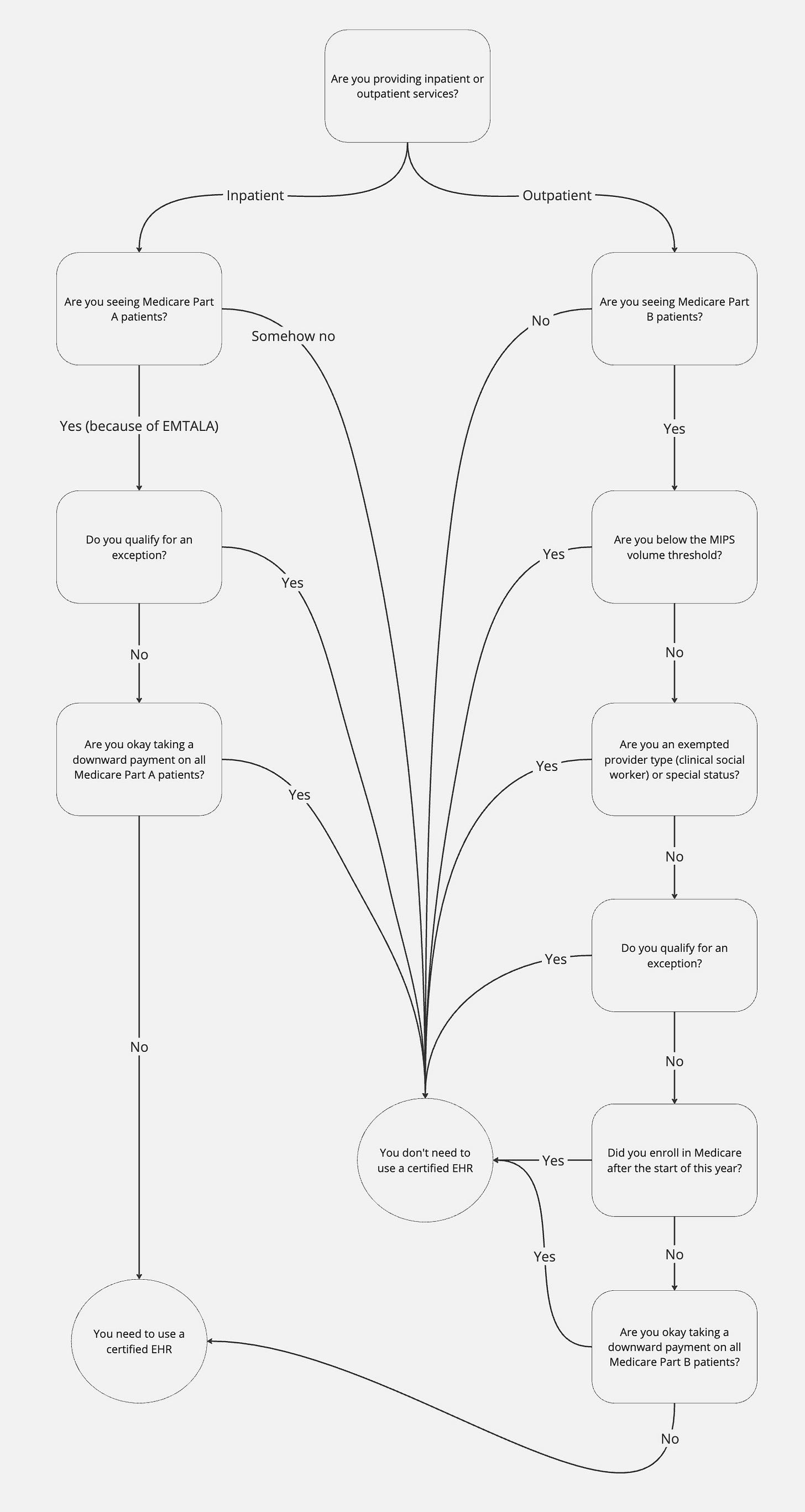

Who does “ONC certification” actually apply to?

With a comprehensive and perhaps overly detailed synopsis of what ONC certification really, truly, and deeply means, the next layer of the EHR onion is who should actually care. The popular narrative (“everyone needs a certified EHR”) isn’t true in a blanket sense as expected.

Insurance Type

First and foremost to that equation is the simple question “Do you see traditional Medicare patients?” While the original Meaningful Use and subsequent programs included Medicaid populations, the federal funding for this slowed and dried up between 2018 and 2021, leading different state Medicaid agencies to end their respective EHR incentive programs in that period. In the current era, Promoting Interoperability and MIPS (as part of QPP) are only focused on Medicare. More specifically, these programs are for Medicare Part A (Promoting Interoperability) and B (MIPS/APM) and not Part C (Medicare Advantage). Thus, if an organization isn’t helping traditional Medicare FFS patients, they aren’t regulated under these programs and they don’t need an ONC-certified EHR.

Care Setting

Inpatient

If you run the numbers quickly, you realize that almost all hospitals end up pursuing Promoting Interoperability and needing a certified EHR. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), a U.S. federal law enacted in 1986, mandates that anyone coming to an emergency department (ED) must be provided with appropriate medical screening and stabilizing treatment, regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay, including Medicare patients. Furthermore, Medicare patients are some of the highest acuity and most likely to need inpatient care.

A subset of hospitals that serve Medicare patients have legitimate reasons that they aren’t using a certified EHR:

Insufficient internet connectivity - Basically, if you’re a hospital operating in a rural area where internet connectivity is a problem, you have bigger fish to fry.

I’m somewhat floored that there might be hospitals in America without sufficient connectivity - it would be fascinating to know if this exception has ever been used.

…One does wonder if the use of Comcast qualifies providers for this, though.

Using decertified EHR technology - if the hospital had an EHR, but their vendor was decertified, it’s obviously not their fault.

This is relatively rare. Using CHPL, we only see 16 out of 716 certified technology entries have statuses related to decertification.

Extreme and uncontrollable circumstances - A catchall for the uncategorizeable. The CMS recognizes that weird shit happens and is willing to listen.

Things like hurricanes and COVID obviously apply here.

I bet these stories are riveting, so I submitted a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to see if we can understand which hospitals have received this exception.

Supposing they do not qualify for an exception, eligible hospitals could actively choose to not use a certified EHR, but this would entail a downward payment adjustment for their Medicare populations. I struggled to find precise details on the exact downward payment, so it’s possible that it’s not that high of a penalty. However, slide 19 of this presentation mentions a 75% downward payment, which is substantial.

Thus, it’s unlikely that the burden of using a certified EHR outweighs the regulatory, operational, and financial cost of foregoing Medicare patients for inpatient care.

Outpatient

In the outpatient world, though, there’s far more nuance, in that there are plenty of outpatient providers that do not treat or seek reimbursement from the CMS for Medicare FFS patients. This could be due to their specialty (pediatricians surprisingly don’t take Medicare patients often) or due to their go-to-market (concierge medicine paid out-of-pocket). This is even more true for tech-enabled care providers, which often focus on cash pay and direct employer sales.

Outpatient provider eligibility

Not all outpatient providers that see Medicare patients are eligible for MIPS, though. The CMS imposes additional eligibility filters for outpatient providers within the MIPS program related to specific provider’s or provider organizations’ specialty and patient volume.

The CMS determines providers’ eligibility by reviewing past and current Medicare Part B claims and Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS) data for clinicians and practices twice a year. As a result, the information is laggy - my wife, for instance, doesn’t even show up when checking usingthe MIPS eligibility tool:

Low volume threshold

If you’re not seeing a ton of Medicare patients and billing the CMS for that volume, the act of reporting is not worth your or the CMS’ effort. To allow for that, the CMS defined a low volume threshold, which is exceeded if a provider:

Bills more than $90,000 for Medicare Part B covered professional services, and

Sees more than 200 Medicare Part B patients, and

Provides more than 200 covered professional services to Medicare Part B patients.

MIPS-eligible clinician-type

Historically, certain clinician types and special statuses (detailed here) were exempt from reporting Promoting Interoperability data via MIPS:

This is changing in 2024, though. Only clinical social workers remain as an excluded clinician type:

Similar to the situation in the inpatient world, the CMS also enumerates a few exceptions that exempt providers from needing to report MIPS Promoting Interoperability measures:

The last point about lack of control exists in MIPS but not in Medicare PI because an individual provider may not have the authority or decision-making about the choice of their EHR if they are part of a larger practice. In this case, the CMS allows them to avoid being penalized for choices out of their control.

Enrollment Period

The most straightforward piece is just that providers are only eligible when they can be fully measured. MIPS eligibility starts on the first of the year, so providers that enroll in Medicare mid-year aren’t required to report (but may do so voluntarily).

Summary

Looking at all these factors, we get this very simple, straightforward, deeply intuitive decision tree:

To fully recap and bring it all home:

Medicare Promoting Interoperability Criteria

Certified EHR

Base EHR

Family health history, PHI capture, measure calculation, and CQM functionality

Medicare Promoting Interoperability Measures

Clinical information reconciliation and incorporation

Electronic prescribing

View, download, and transmit to 3rd party

Transmission to immunization registries

Transmission to public health agencies — syndromic surveillance

Transmission to public health agencies — reportable laboratory tests and value/results

Transmission to public health agencies — electronic case reporting

Transmission to public health agencies — antimicrobial use and resistance reporting

Health IT Module Certification criteria

Privacy and Security

Dependent Criteria

Traditional MIPS Promoting Interoperability Criteria

Certified EHR

Base EHR

Family health history, PHI capture, measure calculation, and CQM functionality

MIPS Promoting Interoperability Measures

Clinical information reconciliation and incorporation

Electronic prescribing

View, download, and transmit to 3rd party

Transmission to immunization registries

Transmission to public health agencies — electronic case reporting

Health IT Module Certification criteria

Privacy and Security

Dependent Criteria

Traditional MIPS Promoting Interoperability Criteria

Certified EHR

Base EHR

Any additional criteria in the specific APM

MIPS Promoting Interoperability Measures

Clinical information reconciliation and incorporation

Electronic prescribing

View, download, and transmit to 3rd party

Transmission to immunization registries

Transmission to public health agencies — electronic case reporting

Health IT Module Certification criteria

Privacy and Security

Dependent Criteria

ONC Certification Hot Takes

We’ve zoomed in to a tremendous level of detail on what EHR certification is and who it affects, but facts, even simplified, are only so interesting. Analysis and opinions are why you are all here, so let’s stray a bit from God’s light (the federal government regulations), read between the lines a bit for some takeaways, and make some predictions.

The removal of Medicaid means some specialties and their EHRs just don’t care anymore

While Medicare encompasses a broad swathe of specialties, it specifically excludes non-medically necessary dental and vision care:

This differs a bit from Medicaid, where:

States must provide dental care to children and can optionally provide dental care to adults (with all states but the exceeding random trio of Alabama, Delaware, and Maryland providing some level of coverage)

Eye exams, eyeglass frames, and lenses are available for children under 21 under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) program and 33 states include vision as a benefit

As noted earlier, the Medicaid portion of the Promoting Interoperability program ended in 2021. So it’s unsurprising to see that many dental and vision EHRs have let their certifications lapse:

Open Dental, Dentrix, DentiMax, Denticon, Eaglesoft, and Umbie DentalCare are all certified for 2014 criteria, but only Dentrix is still active today (and lacks newer criteria like (g)(1), a FHIR API)

Although a few EHRs dropped off from 2014 to now, optometry and ophthalmology-specific EHRs fare a bit better here, with major players like RevolutionEHR, ModMed EMA, and Eyefinity all certified including (g)(10).

The example of dentistry (and to a lesser extent, optometry) shows that the contours and boundaries of the CMS programs do affect vendors’ choices to certify or not.

If you believe that the burden of regulation is a moat against disruption, it logically feels like there’s an opportunity to prove this out with EHRs for these specialties that don’t have certification requirements. The dental and ophthalmology EHRs are pretty mediocre, so go forth and disrupt, young padawan.

Providers and specialty EHR vendors need to pay attention to shifts in MIPS eligibility

The CMS is increasingly looping more and more providers into the certified EHR realm by removing them as exempted provider types. As mentioned before, several specialties were previously exempted, but are included this year and onward.

Physical therapists

Occupational therapists

Qualified speech-language pathologists

Qualified audiologists

Clinical psychologists

Registered dieticians or nutrition professionals

These provider types are also the ones that often have software that’s not the big, generalized EHRs (Epic, Cerner, athenahealth, etc) and instead hyper-specific to their specialty:

Physical therapists frequently use EHRs like WebPT or Clinicient.

Neither is certified today.

Similarly, the software landscape for mental health professionals is extremely fragmented across a slew of behavioral health-specific EHRs: ICANotes, SimplePractice, TheraNest, TherapyNotes, Osmind, Therapyzen, CounSol, and many more

Mental health professionals have long lagged in terms of certified EHR adoption. As Thomas Novak notes, Meaningful Use originally excluded mental health professionals from their definition of eligible professionals for incentives in the HITECH Act, although there have been recent legislative efforts to fix that via the Behavioral Health Information Technology Coordination Act

Capterra lists 300+ for mental health, G2 lists 185, and Reddit has a bunch of threads with therapists discussing myriad options.

Reviewing a few, only the ICANotes EHR appears to be certified in CHPL but lacks more recent criteria, such as (g)(10). However, ICANotes confirmed they have a FHIR API when contacted, indicating that CHPL updates may be delayed.

It will be interesting to track how EHRs serving these niches handle certification, given that those services are reimbursed under Medicare Part B.

Tech-enabled practices and virtual care companies need to think strategically as they build on a headless or decoupled EHR

The headless EHRs can support elements of CEHRT, but they do not provide fully certified solutions out of the box. For example, Medplum and Aidbox are both compliant with data-oriented criteria like (b)(10)’s EHI Export or (g)(10)’s FHIR API but aren’t certified against any other criteria.

Thus, if you choose to build on top of a headless EHR and are hoping to participate in MIPS, you’ll need to ensure you fully meet the CEHRT requirements via a combination of your in-house technology and other off-the-shelf solutions.

Similarly, decoupled EHRs like Canvas Medical, Healthie, or Elation range between “almost a base EHR, but needing a Direct messaging partner for (h)(1)” and “certified EHR”, but still require additional certified products for functionalities related to MIPS Promoting Interoperability measures. These vendors typically have preferred partners or complementary vendors that fill those gaps, so make sure to engage your support team to understand their recommended approach here.

Renewed legislative activity to strengthen and expand regulatory authority here could be beneficial for the ecosystem and innovation

There’s a popular take that Meaningful Use was a mistake. The logic goes that the EHR certification program encouraged the adoption of bad technology, in that the software it forced providers to adopt was different from the digital tools they really needed. It argues that the available software at the time was immature and not ready to cross the chasm, but that the tailwinds foisted it upon doctors in a way that now makes it impregnable to disrupt. Thought leaders opine that the current EHR landscape is one of regulatory capture. I find it all particularly tired and misguided.

Looking at the criteria in EHR certification now, it largely lines up with the criteria a modern practice or hospital needs. The criteria are either super basic table stakes (like electronic order entry or the ability to record demographics) or capabilities that the government wants to see at scale (the ability to send data between providers, the ability to report for public health, etc). While it does represent a bar that any competing software has to clear to full displace the incumbent, these are things you will ultimately need to do anyway if you want to make a competing EHR.

Whether they know it or not, startups and other innovators in healthcare actually pine for more, not less, regulation. Digital applications constantly ask for a uniform set of capabilities to connect to EHRs. One path to that outcome is outright and complete dominance by one or two EHR platforms (akin to iOS and Android). Barring that, the EHR certification program is the main mechanism to enforce consistency across a disparate and fragmented landscape. As seen with our dental example, software vendors that are not regulated do not opt to voluntarily expose capabilities, especially standards-based exchange mechanisms. The expansion of regulatory agency authority (such as the aforementioned Behavioral Health Information Technology Coordination Act) to include broader types of providers or even ancillary applications, such as the picture archiving and communication system (PACS), is necessary to promote uniformity.

AI companies better pay attention

I didn’t want to dive into the specifics of each criteria in this post, but given no good post can do numbers these days without an AI mention, I think it is important to link to my recent post about Decision Support Interventions (b)(11):

"Technology that supports decision-making based on algorithms or models that derive relationships from training data and then produce an output that results in prediction, classification, recommendation, evaluation, or analysis" covers a lot of ground. While the ONC reined in the software explicitly regulated by this in the transition from proposed to finalized rule, it’s still worthwhile for generative AI startups to understand this provision (and perhaps pursue it voluntarily).

As phonetically close as AI is to API, I am still distinctly in amateur status for the former. That being said, it feels like these constraints around sourcing, authorship, equity, and more will be challenging for startups not running their own models.

Conclusion

With that, we’ve done it. We’ve mapped the labyrinth (nearly two decades of overlapping rules), rescuing our baby brother (operating margin) from the clutches of the metaphoric Goblin King (CMS downward payments). We’ve hopefully saved our heroes (your company’s product team) from wandering aimlessly and wasting valuable time.

If you’re an EHR vendor or tech-enabled practice who’s newly considering certification and feeling a bit overwhelmed, feel free to reach out to me and the HTD team:

Big thank you to the coauthor Bobby Guelich (Elion) and the editors and reviewers: Colin Keeler (Kiva), Garrett Rhodes (Redox), and Ayo Omojola (Carbon Health)

Amazing as always. I learned a ton from this one!

Great (& dense) article. But it didn't answer one question. If you submit Medicare claims to CMS, does anyone actually ask you to prove that you used a Certified EHR? Seems to be plenty of cases where CMS says one thing and everyone ignores it (access to patient data & transparent pricing are 2 that come to mind). Eventually CMS may make an example or one or two hospitals. I wonder if anyone is really watching this...